Trump likes to talk about steel and manufactured goods. America’s better trade hope may lie in exported services

When President Trump bemoans the U.S. trade deficit, he’s almost always speaking about goods — steel, beef, lumber, car parts and other products that flow in and out of the country

But the far bigger long-term growth potential and competitive opportunity for turning around America’s trade woes lies with exported services, from financial consulting and insurance to engineering and digital music.

Unlike trade in goods, in which the U.S. ran a deficit of $750 billion last year, the country posted a $250-billion surplus in services the same year. With a handful of exceptions, the U.S. enjoys a surplus in service exports with nearly every other country it trades with.

In the case of a few nations, exports of services turned American trade deficits into surpluses. For example, Trump recently complained about Canada’s $15-billion advantage in trade of goods with the U.S., but when services are counted, it is the U.S. that has an overall $8-billion surplus.

“The real action in the future is trade of services; it’s large and growing rapidly,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.

He and others see the lack of attention given to U.S. service exports as a lost opportunity.

If we pick a fight with the rest of the world [on goods], that’s going to short-circuit the trade in services.

— Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics

Exports account for just 4% of the sales of U.S. services that are tradeable, compared with about 20% of American manufactured goods, said J. Bradford Jensen, a professor at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business and a leading expert on services trade. And while 1 out of 4 U.S. manufacturers export, only 5% of businesses that provide exportable services do so.

“I don’t think anyone disputes that the United States has globally competitive service firms — finance, insurance, the Internet, Hollywood, music, architects, engineers, R&D scientists — all that stuff, we’re as good as they come,” Jensen said. “And yet we’re not exporting a lot of that to countries that need them, like China and India.”

It’s not unusual for the public, or presidents, to link trade with manufactured goods that are loaded into containers and shipped in ocean waters. Trump has gone further by making trade and manufacturing jobs his top economic priority, though — something that many economists criticize as a misguided fixation.

That focus on manufactured goods has led Trump to lash out at trading partners like Mexico, threatening to slap tariffs on imported products and tear up trade pacts such as the North American Free Trade Agreement.

But experts say such moves could backfire by sparking a trade war that would inevitably spread to service exports.

“If we pick a fight with the rest of the world [on goods], that’s going to short-circuit the trade in services,” Zandi said.

Worldwide, growth of trade in services has been outstripping that of goods over the last quarter century. Not all services are tradeable; hotels, restaurants and home healthcare providers can’t export their labor-intensive services. But some of the fastest-growing and most lucrative services can, such as professional and technical work.

U.S. exports of services to China, for example, have tripled since the Great Recession in 2009, to more than $53 billion last year. They include sales of Microsoft software, Hollywood movies, maintenance work on Boeing aircraft in China, as well as an array of services related to the Asian country’s infrastructure development and environmental improvements.

Also counted as exports of services are royalty revenues and fees collected for patents and licenses. That would include, for example, the potential future earnings for Trump, who recently received provisional approval from Beijing for trademarks of the Trump brand that could end up on hotels, golf courses and other businesses, just as in the U.S.

The U.S. currently has a trade surplus with almost every country. India stands out as the biggest exception, thanks to that country’s exports of I.T. services, including revenues from U.S. companies contracting with call centers in India.

Experts say American service providers would be selling more abroad were it not for a wide variety of barriers in overseas markets. Many countries are even more protective of their services than manufactured goods, such as banking, telecommunications and sectors that disseminate information.

The Obama administration sought to break down some of those barriers in negotiating the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the trade agreement with 11 other nations that span the Pacific Ocean. As a candidate, Trump sharply criticized the agreement as a bad deal for America, and he canceled the pending pact as soon as he took office.

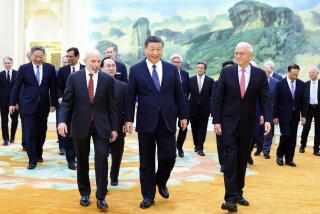

Even so, Trump’s trade team is expected to incorporate some of the provisions and language on services reached in the Trans-Pacific Partnership. And last week, the White House announced a trade deal with Beijing in which China agreed to take steps to open access to its financial markets, including for U.S. providers of electronic payment services.

Positive as that news was, American services firms said they would not know the actual impact until licenses are approved and banks in China issue foreign brand cards for domestic use, according to the Coalition of Services Industries, a Washington trade group.

If barriers to services exports remain, it’s partly because the U.S. has paid relatively little attention to the problem.

“The U.S. has a comparative advantage in services, but in a sense it’s not doing as much to exploit this advantage,” said Andrea Ariu, a post-doctoral fellow at the Geneva School of Economics and Management who has researched services trade in the world.

All the short-term attention on trade and manufacturing jobs will not help America’s economic competitiveness down the road, he said, noting that other countries are investing more in developing exportable services like scientific research, to win contracts, for example, for specialized measurements or lab analyses of materials.

“Ten to 15 years from now, I’m pretty sure China will develop the services sector a lot. They might become as good as the U.K. and the U.S. one day,” Ariu said.

To some analysts, the Trump administration’s rationale for focusing on manufacturing and trade rests partly on nostalgia and outdated economic statistics.

Trump has talked of returning America to its glory days when it was an industrial powerhouse, but manufacturing today accounts for 8.5% of total U.S. employment, down from 25% in the 1970s. Industrial output now represents only 12% of the nation’s gross domestic product.

Trump administration officials wistfully point to Germany, which has a large trade surplus with the U.S. and the rest of the world, and where manufacturing still makes up 20% of employment. But what’s not often noted is that Germany’s factory payrolls too have shrunk, by about half since 1970 as a share of overall employment, as manufacturing has become much more automated and globalized.

Peter Navarro, a trade and manufacturing policy adviser to Trump, argues that manufacturing is what matters in trade because it pays significantly higher wages than services and has a much bigger ripple effect on the rest of the economy. But that thinking, too, looks outmoded.

With the decline of unions, outsourcing and global competitive pressures, average manufacturing wages in the U.S. have fallen behind those of the services sector at large.

Excluding supervisors, the hourly pay of U.S. manufacturing workers has increased at an average annual rate of 1.9% over the last decade, compared with 2.9% for the service-producing economy, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The result is that factory workers today make on average $20.43 an hour, 90 cents less than service workers. It was the other way around in 2005.

The gap in pay is even bigger when comparing the average production worker with those in business and professional services, whose earnings are more than 20% higher.

What’s more, experts say trade in services is not only growing at a faster rate but is much larger than government statistics indicate. While traded products are measured as they pass through customs, services are harder to track and sometimes hidden in the value of manufactured goods.

“What you would not see reported anywhere necessarily is the amount of services and labor that went into production and servicing of exports,” said Christine Bliss, president of the Coalition of Services Industries.

In Rochester, Mich., Rob Patterson and Kevin Zalewski export personalized, customized-bound books. The company is called LoveBook, inspired by the hand-made notebook filled with sweet inscriptions that Patterson first gave to his wife as a gift.

Seven years on, LoveBook now has 16 employees and more than $10 million in sales, and about 40% of that is exports. But most of what it sells abroad are not manufactured goods — they’re digital books sold to Britain, Australia and dozens of other countries. The digital versions are sent to local printing shops, which then produce the books and ship them to customers.

LoveBook doesn’t face traditional barriers like tariffs. What keeps its business from growing faster is better transportation services and greater ability to market, especially in developing countries where U.S.-based social media and other information technology services are met with obstacles. Facebook is banned in China, for example, and it’s common for governments to restrict the free flow and storage of data across borders.

“It seems people are used to developing policy based on old-fashioned goods,” said Patterson, 43, himself a former employee of an old-line consumer products manufacturer.

“The top companies 20 to 30 years ago were auto companies and appliance and other manufacturers of goods,” he said. “But you’re seeing this shift to companies that deal in data rather than in tangible products. That’s the way a lot of the market is going.”

Follow me at @dleelatimes