‘Home away from home’: After fires razed their houses, safari workers find relief in saving animals

The day after the fire, Terry Cotter couldn’t walk from the parking lot to the dinner tables at Safari West without someone hugging him and offering condolences.

A tour guide at the private Africa-inspired wildlife park, Cotter was one of at least 10 staff members whose homes burned Oct. 8 when a series of deadly fires tore through Napa and Sonoma counties, destroying more than 5,000 structures and killing more than 40 people.

Cotter, 76, and his wife, Liza, were on Amelia Island in Florida the night of the fire, checking on that home for hurricane damage (it was fine) when their niece called to reassure them she’d made it out in the evacuations. The couple immediately flew back to California.

And the next day, like many park employees who lost their possessions, Cotter went to work.

“This is great therapy. It diverts your mind from other stuff, the things you lost. Here you’re with people that also lost it,” Cotter said Wednesday. “You’re not alone; everyone is in this together.”

Every bit of hope helps, workers say. About five days after the fire ran through the area, an endangered baby antelope workers named “Tubbs” was born, much to the delight of staff. It died a few days later from intestinal complications, a park spokeswoman said. But not long after that, park owner Peter Lang said he saw a guinea fowl guiding 15 new babies, or keets, down the road.

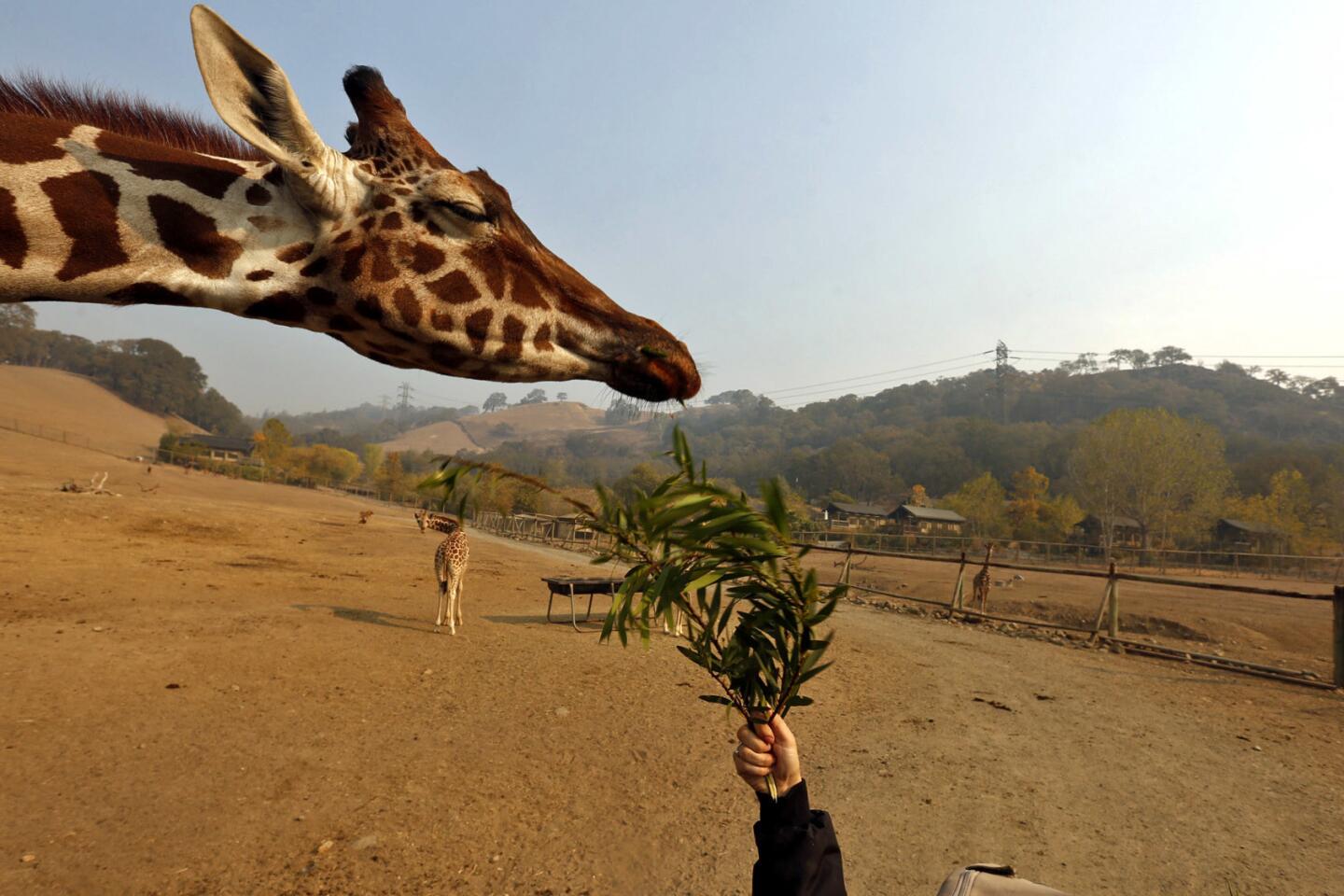

The Safari West preserve sits on 400 acres of forest and grassland secluded among the rolling hills of the Mayacamas Mountains in unincorporated Sonoma County. The preserve holds more than 1,000 animals such as exotic birds, giraffes, cheetahs, hyenas and rhinos. There are 30 tents for extended stays and dozens of vehicles to drive people out into the “Sonoma Serengeti.”

Cotter’s home is at the edge of the park’s western boundary and was destroyed with hundreds of others in the pocket communities off Potter Creek Road in the surrounding area.

In the days since the wildfires laid waste to the area, employees have sought refuge in their work with each other and the animals. So have first responders. Earlier this week, about two dozen firefighters showed up unannounced in their bright red trucks and yellow turnout gear for a morale-boosting park tour.

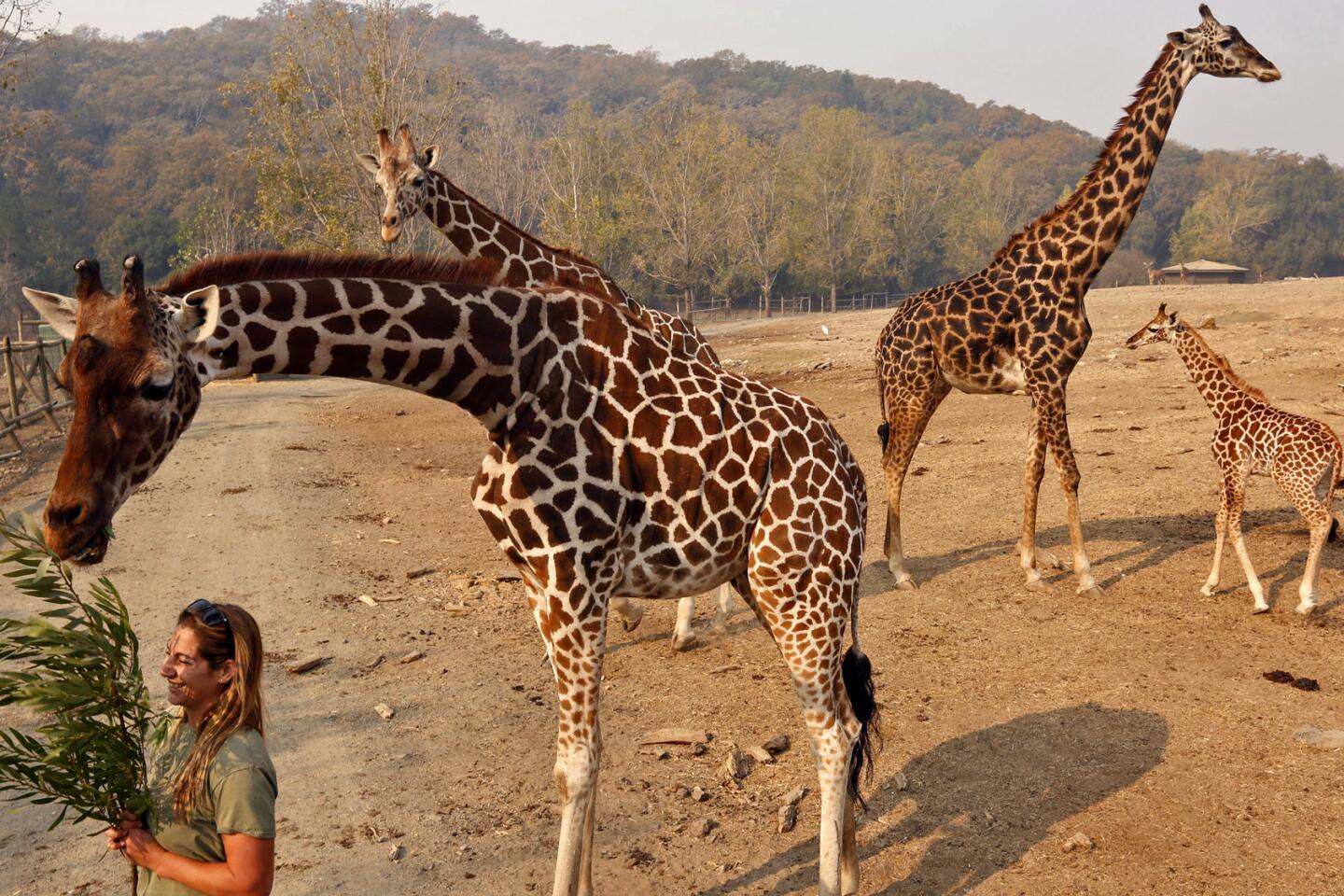

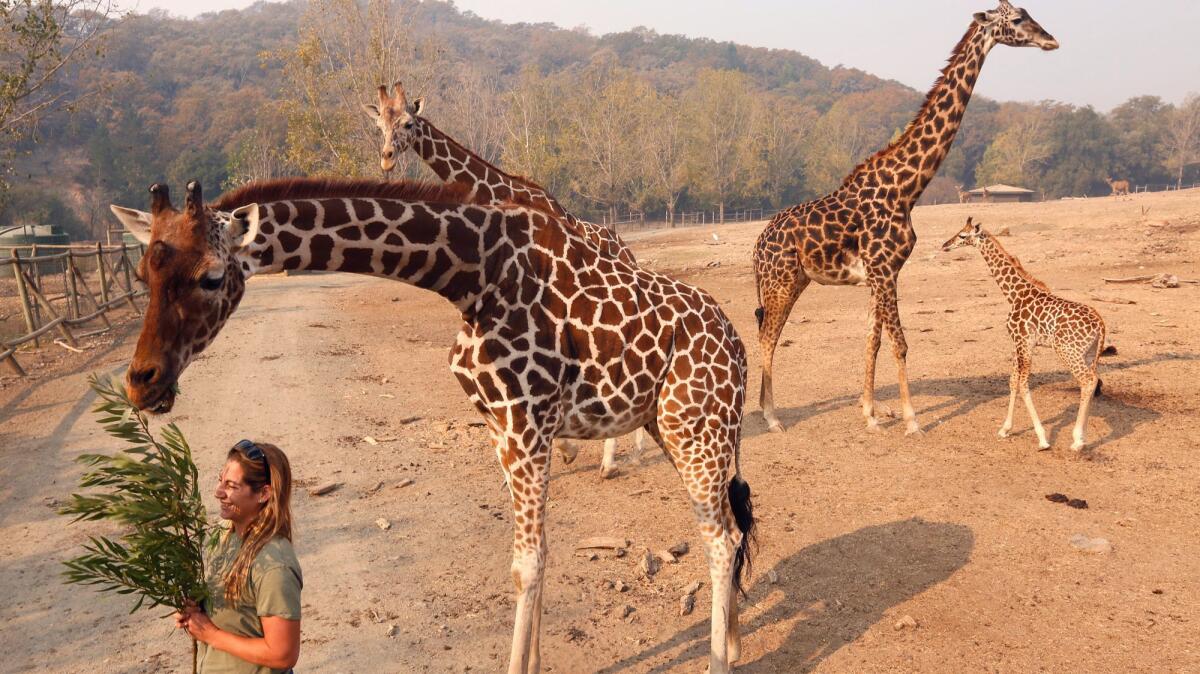

Marie Barbera and other employees were happy to oblige, saying people leave with a sense of the “magical.”

“This is home. Even for people who lost their home…this is home away from home,” said Barbera, 48, who has worked at the park nearly since its founding in 1993 and was evacuated three times the night the Tubbs fire raced down into the Sonoma Valley. “The community we have here, it’s always been a family.”

A tour of the park property shows how close all of it came to being lost, if not for Lang’s efforts the night of the fire.

Lang, 76, lives on a five-home, 200-acre ranch with his wife, Nancy, about a mile uphill from Safari West. The night of the Tubbs fire the park’s lead mechanic, who lives on the Safari West property, raced up to Lang’s home and alerted the couple that the park was in danger and its guests were being evacuated.

When Lang arrived, firefighters, sheriff’s deputies and park staff were clearing out the property. Employees who had been communicating through texts about the emergency had formed a convoy down in Sonoma Valley and raced up to the park together to try to save it, Barbera said.

“We train for this. We have drills with other zoos. We always plan for a two- to four-hour window. There was no time,” Barbera said.

When the guests were gone, authorities ordered the rest of the park evacuated too, but Lang stayed. He told his staff to leave.

“The way we looked at it, we were going to lose all the animals and him,” Barbera said. “It was so big it was impossible to believe that it would be there when we got back.”

Through the rest of the night amid dying winds, Lang fought the fire creeping down the hills onto his property alone. He was armed with only a garden hose and hundreds of feet of extensions and protected by a hoodie that he had to continually drench to avoid burns.

“I tell you, I soaked that hoodie and sweatshirt about every 10 minutes. I’d be turning that hose back on myself because it was that hot,” Lang said, still wearing the suede shoes and dirty jeans he had on the night of the fire. “It was smoky, it was hot and you knew you were alone.”

Lang attacked the spot fires wherever they popped up — in the tall grass near the hyenas, at the edge of the barn where the giraffes sleep on the park’s west side, and on a grass-lined dirt road near the Cape buffalo and aviary. He drove his truck over embers, jumped out and stomped out others with his shoes. He guided a group of nyala through flames to safety and used a forklift to move pallets of burning poles away from a neighbor’s home so it didn’t ignite and launch more embers into the air.

“It’s not a big, drawn-out, long thought process. You just make decisions and you keep going,” he said.

At one point during the fight, Lang looked northeast toward his 200-acre ranch property. The flames were sky-high.

“You go through a process. I can see the mountain where my house is lit up. I know they’re going up,” he said. “You’re down there for a lot of hours and you have time to reflect.”

Lang designed his main ranch home with an architect. A world-adventurer whose body of work includes jobs in deep sea fishing, oil drilling, property development and woodworking, he said his taste in art and cultural pieces have refined over years traveling in Africa and Central America.

His home uphill was filled with first-edition books, fine art, Panamanian baskets and minerals including vibrant green malachite, deep blue azurite and an amethyst tower.

“I did go up there Monday morning and was stunned that everything was gone,” Lang said. “It’s not burned. It’s gone.”

The first 48 hours were traumatic and emotional, he said. But he also called himself lucky. He has an old home on the Safari West property where he and his wife are now staying while they plan to rebuild on the ranch.

Cash raised through a GoFundMe account set up for him by a community member has instead been distributed to employees who lost their homes. Many of them return every day to the park to work.

“I knew they would. They’re dedicated,” Lang said.

As the slow process of rebuilding Sonoma County begins, Lang and park staff are repairing fences and other infrastructure damaged on the property. No animals were lost.

“It’s very cathartic…as long as you got a project,” Lang said.

The park is expected to reopen March 1.

For breaking California news, follow @JosephSerna on Twitter.

ALSO

California’s deadliest fires set off debate about illegal immigration and sanctuary policies

Insured losses top $1 billion in Northern California fires

He wouldn’t evacuate, then used Facebook Live to broadcast firestorm in his hometown

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.