Arthur Rosenfeld, ‘godfather’ of energy efficiency who helped consumers save billions on electric bills, dies at 90

California’s role as a world leader in energy efficiency can be traced in good part to a laboratory in Berkeley where a physicist named Arthur Rosenfeld spent much of his career searching for new ways to conserve power and then campaigning for their use.

His efforts were so far-reaching that — as his ideas and practical conservation methods swept the nation — he was credited with saving American consumers billions on their energy bills.

Rosenfeld died Jan. 27 at age 90 in Berkeley, not far from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory where he became known as the “godfather” of energy efficiency.

The slight, bespectacled Alabama native also was a commissioner at the California Energy Commission and an adviser to the U.S. Department of Energy for energy efficiency and renewable energy.

Over the years he received numerous awards and honors, including the National Medal of Technology and Innovation in 2011 – the nation’s highest honor for technological achievement – for the development of energy efficient building technologies.

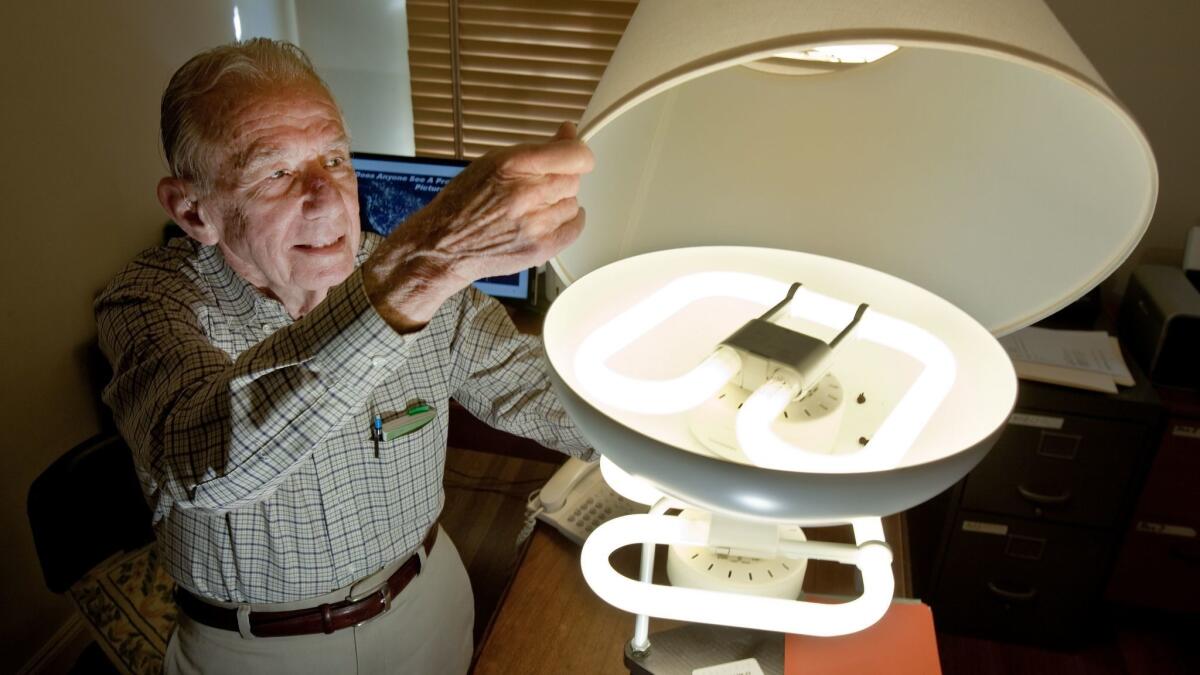

Rosenfeld spent decades doing rigorous analyses that led to breakthroughs in reduced energy for lighting, windows, buildings, refrigerators, televisions and other electronics, while persuading policymakers and utilities to implement his energy-saving ideas.

To use economic terms, Rosenfeld believed the key to energy efficiency was reducing its demand, rather than being preoccupied with increasing energy supplies to accommodate California’s rapid growth.

Rosenfeld not only was “technically brilliant” he also “was so enthusiastic about the things he believed in that you wanted to learn from him,” said Kathryn Phillips, director of the Sierra Club in California.

A key moment in Rosenfeld’s quest to find energy savings occurred on a November night in 1973 during the Arab oil embargo, when oil prices soared and frustrated drivers waited in long lines to buy gasoline.

After turning off the lights in his UC Berkeley office as usual, Rosenfeld started calculating the oil-equivalent savings of turning off the lights in all 20 offices on his floor, and he then proceeded to do just that. He also decided to dedicate himself to conservation.

“The cheapest energy is what you don’t use” became Rosenfeld’s guiding mantra. “It would be more profitable to attack our own wasteful energy use than to attack OPEC,” he once said.

Gov. Jerry Brown recalled that during his first term as governor in 1975, Rosenfeld told him that simply by requiring more efficient refrigerators, California could save as much energy as would be produced by the then-proposed Sundesert Nuclear Power plant.

“We adopted Art’s refrigerator standards and many others, did not build the power plant and moved the country to greater energy efficiency,” Brown said in a statement after Rosenfeld’s death was announced on the Berkeley Lab website.

His admirers noted that the rewards of his diligence could be clearly seen in California where residents today use about the same amount of electricity per capita that they did 30 years ago.

Rosenfeld was born in 1926 in Birmingham, Ala., and spent his early years in New Orleans during the Depression and in Egypt, where his father was an expert in sugar-cane cultivation.

The younger Rosenfeld returned to the United States to get his bachelor’s degree in industrial physics at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, taught radar operators at Navy Pier in Chicago during World War II, then studied particle physics at the University of Chicago under the legendary Enrico Fermi, who built the world’s first nuclear reactor.

In 1954, Rosenfeld took a position at UC Berkeley at what would become the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. He founded what later would become the Lab’s Energy Technologies Area.

Rosenfeld’s stint as an adviser to the Energy Department was during the Clinton Administration from 1994 through 1999, and he was a California Energy Commission commissioner from 2000 to 2010.

In 2006, Rosenfeld won the Enrico Fermi Award, a prestigious science and technology award named after his former teacher and presented by the U.S. Energy Department.

In the tributes to Rosenfeld, many recalled not only his scientific skills but his engaging personality. He was polite, affable, passionate, had a quick wit and could explain scientific matters to the general public. He also was a mentor for others who helped develop energy conservation.

“Over the years, I grew to appreciate how his indefatigable, high-energy devotion to our energy challenges became a role model for a large number of younger scientists, including myself,” former U.S. Energy Secretary Steven Chu said in a statement.

Rosenfeld is survived by daughters Margaret and Anne and six grandchildren.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.