Editorial: Trump’s tax-code plan is short on reform and long on tax cuts for the wealthy

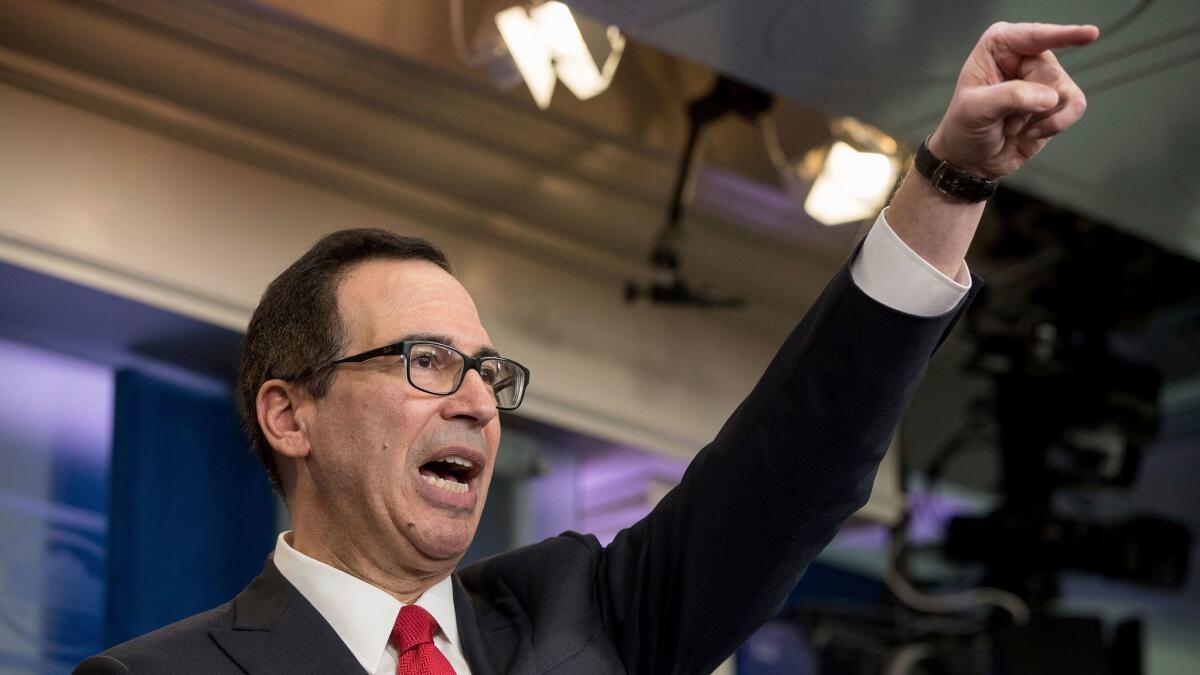

Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin laid out the Trump administration’s blueprint for tax cuts Wednesday, and like much of what the administration has done thus far, it was long on promises but short on detail and realism. We’d welcome White House leadership on a bipartisan effort to clean up the overly complex and easily gamed U.S. tax code, as President Reagan and Congress attempted in the Tax Reform Act of 1986. But that goal has taken a back seat to President Trump’s desire for headline-grabbing tax cuts that would pile on more debt and widen the gap between rich Americans and everyone else.

Administration officials had been promising a plan that would iron out so many of the wrinkles in the tax code that the vast majority of Americans could file their annual returns on a form no bigger than a postcard. And perhaps they will offer such a proposal someday. What Mnuchin shared Wednesday, though, was a one-page outline with 11 bullet points, none of which addressed the biggest problems with the tax code — including the multiple categories of income and the byzantine rules for calculating what portion of that money is taxable.

Granted, we’re barely four months into Trump’s term, and tax policy is as difficult as they come. It’s probably too much to ask for a fully baked plan at this point. But a coherent and credible outline of a plan with a clear and worthwhile goal is not too much to ask for, and it’s hard to discern one here.

Washington can’t push a button on tax cuts and make the economy grow; that’s akin to eating sugar in the hope that it will help you run a marathon.

Tax cuts to stimulate the economy make some sense when the nation is in a recession and unemployment is high, leaving a lot of capacity unused. The problem with the U.S. economy today is different: The recession is long over and unemployment is low, but we remain stuck with slow growth, held back by low productivity gains and an aging workforce. Even rock-bottom interest rates haven’t helped the economy break out of its rut.

A tax reform plan that made the code more efficient while removing disincentives to invest and take risks could help promote growth over the long term, and there are a few elements of Trump’s blueprint that aim in that direction. For example, it tries to reduce the incentive for large U.S. businesses to leave profits overseas — they’ve stashed an estimated $2.5 trillion on the books of their foreign subsidiaries— instead of reinvesting them here. That’s a good goal, if it can be paired with an effective way to prevent U.S. companies from shifting their profits to foreign tax havens.

But aside from having something else to tout for Trump’s first 100 days, the administration’s main interest appears to be enacting “the biggest individual and business tax cut in American history,” not overhauling the code. To that end, the blueprint calls for lowering most individual tax rates modestly (although the effect could be dramatic, depending on how the brackets are structured) and business rates dramatically, from a top rate of 35% to 15%.

The immediate problem with that idea is the potentially enormous increase in the federal debt. According to the budget hawks at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Trump’s cuts could result in an additional $5.5-trillion increase in the federal debt over 10 years beyond the current, deficit-laden path. That’s even factoring in the elimination of “targeted tax breaks that mainly benefit the wealthiest taxpayers” and “tax breaks for special interests.” What these might be wasn’t disclosed, although Mnuchin suggested ending the federal tax deduction for state and local income taxes — a break enjoyed by millions of middle-income taxpayers in California and other high-tax (read: “blue”) states.

Mnuchin argued that the deep cuts would pay for themselves by spurring the economy to grow fast enough to make up for all the lost revenue, but that’s magical thinking. Again, Washington can’t push a button on tax cuts and make the economy grow; that’s akin to eating sugar in the hope that it will help you run a marathon.

The one clear beneficiary of the Trump plan would be highly paid professionals who work in partnerships, small companies and as solo practitioners — like, say, the limited partnerships Trump formed for his real estate ventures. Today, the income those taxpayers collect from their businesses are taxed at the same rate as an ordinary worker’s paycheck, up to a maximum of 39.6%. The Trump outline would instead apply the same rate as large corporations — 15%.

That change would create a whole new incentive to game the tax code, encouraging corporations to change how they’re structured or how their employees are classified in order to slash workers’ tax payments. What goal would this serve? It’s just another one of the confounding aspects of Trump’s tax plan.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.