Our national parks can also be reminders of America’s history of race and civil rights

REPORTING FROM TULELAKE, CALIF.

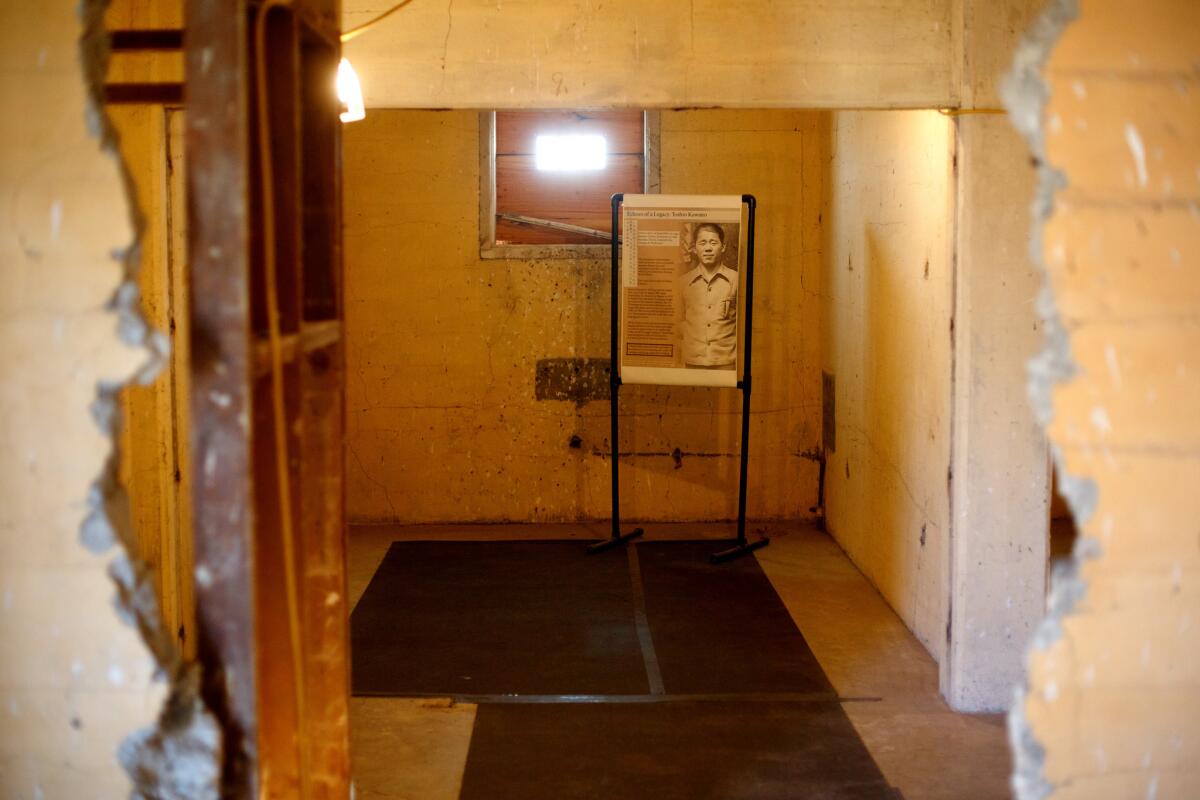

On a late October afternoon, as icy shards of rain pelleted the high desert, Angela Sutton pries open the metal door that seals off the old jail that once belonged to the Tule Lake war relocation camp.

The door swings open and we step into the pitch darkness, into air redolent of musty concrete.

Tule Lake, in a rural community in Northern California just a few minutes shy of the Oregon line, was the biggest and most notorious of the Japanese American internment camps established by the U.S. government during World War II, when almost 120,000 people (mainly U.S. citizens) were incarcerated for no other reason than their ancestry.

The jail is one of the camp’s few remnants and is now maintained by the National Park Service — one of a rising number of such sites that deal with contentious issues of race and ethnicity in American history.

Full series: Celebrating our national parks »

Sutton, an energetic young ranger who has worked with the Tule Lake Unit since it was established in 2008, picks her way through the darkness and brings a flashlight beam to rest on one corner.

It illuminates three columns of faded Japanese characters, marking a name and birth date: “Kawano, Toshio, year of 1919” — a man leaving humble evidence of his existence in what must have been dire circumstances.

“One piece of graffiti tells us this story of a person,” Sutton said. “And that is just one story of the thousands of people that came through this camp.”

When the National Park Service was established 100 years ago, it was with the intent of creating a federal agency that would “conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects” in the nation’s wilderness area. But over the decades, the NPS’ portfolio has expanded. Of its 413 units, more than a third are historic places and sites — and it’s through some of these that the park service has begun dialogues about race.

‘Complete American narrative’

That is the case at Tule Lake, as well as at the Nicodemus National Historic Site in Kansas, which harbors a roughly century-old settlement established by freed slaves after the Civil War, and the 54-mile Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail in Alabama, which marks the path of the fraught 1965 march to secure equal voting rights for African Americans in the U.S.

“It’s an inherent mission and responsibility to tell the complete American narrative,” said NPS Director John Jarvis. “Not just the good and rosy stories, but the full story.”

That may raise an eyebrow given the diversity issues that have plagued the park service — from its disproportionately white visitor pool to its largely white staff. But the service has made inroads in recent years, and 20% of its staff is now composed of minorities.

Plus, Jarvis thinks the development of sites such as Tule Lake can continue to alter the equation.

“By tackling these issues, we have the potential to change both the demographics of our visitation and our work force,” he said.

He also noted that the park service has a long track record of interpreting American history. (It has managed Civil War battlefields since the 1930s.)

But it’s been only relatively recently that it has grown comfortable addressing issues of race. Case in point: those Civil War battlefields. For much of the 20th century, interpretation at these sites avoided the issue of slavery, focusing instead on anecdotes about battle strategy and historical armaments.

“It was just an unwritten policy from the ’30s until the mid 1990s — 60 years — that the park service just didn’t want to go there,” said Dwight T. Pitcaithley, a historian at New Mexico State University, who has also served as chief historian for the NPS.

These aren’t just sites of Japanese American history or African American history. They are sites of American history.

— Myron Floyd

That began to change in the 1990s, with the approaching sesquicentennial of the Civil War, when parks began to incorporate discussions of slavery into their materials and guided tours.

It was also during the ’90s that the NPS began to establish and manage historic sites that directly addressed issues of race and civil rights — including Nicodemus, Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas (where in 1957 the Army helped to forcibly desegregate the student body on the orders of President Eisenhower) and Manzanar, the former Japanese American internment camp in the Owens Valley 220 miles north of Los Angeles.

In California, others have been added since.

There is the César E. Chávez National Monument, in bucolic Keene, outside of Bakersfield. The site was an organizing center for the farmworker movement of the ’60s and ’70s and serves as the final resting place of the Mexican American labor leader whose struggles often intersected with issues of race and civil rights.

The monument, established in 2012, is still in its infancy; it’s in the process of creating the interpretive plan that will tell the myriad stories of the farmworker movement, which involved key contributions from women and Filipino organizers.

The inclusion of such sites in the NPS portfolio makes an important statement, said Myron Floyd, who oversees the department of recreation and tourism management at North Carolina State University and who has studied issues of diversity in the national parks.

“It’s saying that these are places or histories of national significance,” he said. “These aren’t just sites of Japanese American history or African American history. They are sites of American history.”

And as such, they illuminate aspects of U.S. history that don’t always get a lot of play in the textbooks.

Powerful stories

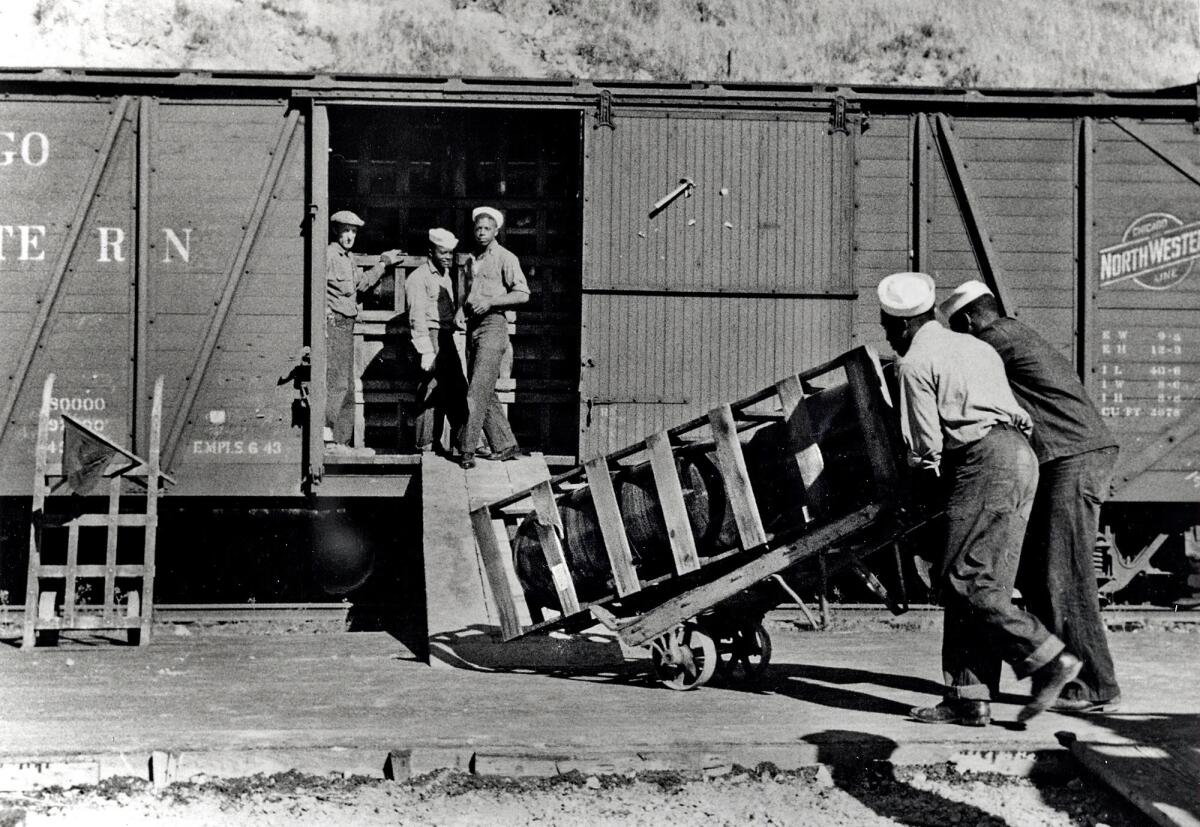

Historical photo taken after the blast of some 5000 tons of TNT that rocked the U.S. Navy’s Port Chicago on July 17, 1944, kiling 320 people. This is an Exterior view of barracks with sailors visible in windows.

In late October, shortly after my visit to Tule Lake, I found myself standing over the remnants of an old pier in Suisun Bay, near Concord, Calif.

The Port Chicago Naval Magazine was an important World War II-era site, where segregated units of African American seaman — with little training or proper equipment — had the arduous, life-threatening task of loading munitions onto ships for the war effort in the Pacific.

In July 1944, an accident lighted up a pair of munitions ships and triggered an explosion so massive that it registered 3.4 on the Richter scale. The 320 men on site, most of them African American, were killed instantly. For most, their remains were never found.

320 men on site, most of them African American, were killed instantly.

After the disaster, 258 black seamen refused to continue loading because they feared a similar fate. The Navy threatened them with mutiny charges, and 50 men were ultimately convicted — convictions that were never overturned. But the widely publicized case helped launch a debate that eventually led to the desegregation of the armed forces in 1948.

Port Chicago is complicated to visit. (It’s on an active military base and tours can be canceled at any time.) All that remains of the site is a triangular arrangement of battered wood pilings. But the stories it tells — of race and injustice, of war and change — couldn’t be more powerful.

“You don’t hear about this on the History Channel,” ranger Stephanie Meckler said as she walked a small clutch of visitors along the bay, the sound of water lapping on the shore.

“This story gets passed around through conversation.”

The NPS has helped keep that conversation alive.

Telling the other stories at Tulelake and Manzanar

Visit the town of Tulelake, Calif., today and you will find a spot that is more field than town, a place where arrow-straight highways pierce plantings of potatoes and onions.

It is small, with a population of about 1,000 — many descended from 19th century pioneers.

It is also remote — hugging California 139 in the austerely beautiful Modoc Plateau, known for craggy outcroppings of ancient lava. The nearest interstate is 77 miles away; the nearest major commercial airport, more than 100.

Its isolation led the U.S. government to choose it as the location for the largest and most punitive of its World War II-era Japanese internment camps.

Japanese Americans deemed “disloyal” were sent to the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, the only one of the 10 camps with a stockade and jail.

At its peak, it housed nearly 19,000 people, making it the most populous California settlement north of Sacramento. (Among them: future “Star Trek” actor George Takei.)

“It was like a city,” said Angela Sutton, a fourth-generation Tulelake native who works as a ranger for the National Park Service, which manages what’s left of the camp.

“There were 300 people to a block, 28 bathrooms to a block — people were really jammed in there.”

Today, little remains of the internment center — a few building foundations, a handful of weathered barracks and the chilly jail — that was spread over various sites around Tulelake.

This includes the Tule Lake Segregation Center, where tens of thousands of people were held, as well as Camp Tulelake, an old Civilian Conservation Corps camp that served as an early detention center for Japanese American resisters, and later for German and Italian prisoners of war.

“Our mandate is to tell the story of Japanese Americans at Tule Lake,” said Larry Whalon, who oversees the Tule Lake site —one of a series of park service units that commemorate World War II in the Pacific — as well as the nearby Lava Beds National Monument.

“But we also need to tell the other stories too: What the place was like before, the story of the Native Americans, the story of the lake, of agriculture, of the people who lived there, the stories that came after.

“All of those stories give context.”

It’s a story that the rangers at Manzanar National Historic Site, California’s other Japanese American interment camp, in the Owens Valley, about 220 miles north of Los Angeles, have been developing for more than two decades.

That site, a square-mile park within view of Mt. Whitney, contains robust displays on the incarceration experience that include audio of oral histories with survivors.

“It’s a history that is still alive,” said Alisa Lynch, Manzanar’s longtime chief of interpretation. “We can connect with people who experienced it. It’s a history that is relevant today.”

“Relevant” is a word you’ll hear a lot of at Tule Lake and Manzanar:

Sutton said it’s a story worth examining.

“We take a dark spot in our own history, something other countries might want to cover up,” she said, “and we maintain it and preserve it so that future generations can learn.”

A journey to Tule Lake couldn’t be timelier.

Visiting NPS sites in California

With national park sites spread around remote parts of California, get ready to do a little flying and a lot of driving.

Tule Lake Unit

How to get there: United offers connecting service (change of planes) to Redding, one of the main points of departure for visits to the park. Restricted round-trip airfare from $459, including taxes and fees. From Redding, it’s a scenic 154-mile drive north on Interstate 5, before switching to U.S. 97 and California 161 and 139.

When to visit: The visitor center is staffed from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Memorial Day to Labor Day, but the only way to enter the sites is on a ranger-led tour. During the season, two-hour tours of the Tule Lake Segregation Center are given at 10 a.m. Saturdays (except on the first Saturday of each month, when it is at 1 p.m.). One-hour tours of Camp Tule Lake are at 1 p.m. Saturdays. (except the first Saturday of the month, when the tour is canceled). Guided visits can be scheduled for other times with two weeks’ notice by calling (530) 260-0537.

Conditions: Tule Lake is 4,035 feet above sea level in high desert, so temperatures can fluctuate wildly — from 40 to 80 degrees in a single day in the peak of summer. There is regular snowfall from November through March.

Information: The National Park Service office is inside the Tulelake-Butte Valley Fairgrounds office at 800 Main St., Tulelake ([530] 260-0537 or [530] 667-8113), where there is a small museum that includes displays on the segregation center.

Sleep: Fe’s Bed and Breakfast, 660 Main St., Tulelake; (541) 892-2892, (877) 478-0184. A wooden home with four bedrooms has shared baths and hearty breakfasts. Doubles from $80.

Port Chicago Naval Magazine

How to get there: Port Chicago is in Concord, in the greater Bay Area, and is accessed through the park service office in Martinez, 28 miles northeast of Oakland and 38 miles northeast of San Francisco.

How to visit: Because the site is on an active military base, access is exclusively through a 90-minute ranger-led tour at 12:45 p.m. Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays. These require reservations two weeks in advance and a valid, government-issued ID. To reserve: (925) 228-8860, Ext. 6520.

Information: The National Park Service office for Port Chicago is at the John Muir National Historic Site, 4202 Alhambra Ave., Martine; (925) 228-8860, Ext. 6520.

Manzanar National Historic Site

How to get there: Manzanar is about 220 miles north of downtown Los Angeles in the Owens Valley, off U.S. 395 between Lone Pine and Independence.

When to visit: The park is open 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily. Visitors can go on self-guided tours of the on-site museum and tour the camp on foot and by car.

Conditions: The park is in the high desert at 3,727 feet, and the weather can be extreme and windy, with winter highs of 40 degrees and summer temperatures in the 100s.

Information: The National Park Service office is at 5001 Highway 395, Independence; (760) 878-2194, Ext. 3310..

Sleep: Dow Villa Motel, 310 S. Main St., Lone Pine; (760) 876-5521. A 1923 inn where John Wayne once stayed features 92 rooms (20 have shared bathrooms) spread through a historic building as well as a comfortable new motel-style wing. Winter season doubles from $70; summer season from $90.

César E. Chavez National Monument

How to get there: The site is in the Tehachapi Mountains 31 miles east of Bakersfield and about 127 miles north of downtown Los Angeles off California 58.

When to visit: The park is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. daily, and visitors are welcome to explore the gallery and the Chavez burial site on self-guided tours.

Information: 29700 Woodford-Tehachapi Road., Keene, Calif.; (661) 823-6134.

Sleep: Padre Hotel, 1702 18th St., Bakersfield; (661) 427-4900. This Spanish revival structure from 1928 was recently revamped. It has 112 rooms, a cafe and a popular bar. Doubles from $129.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

Produced by Denise Florez

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.