Samuel Charters dies at 85; influential historian of blues and jazz

Samuel Charters, a vital historian of American blues, folk and jazz who helped introduce a generation of music lovers to Robert Johnson, Blind Willie McTell and other performers, died Wednesday in Stockholm. He was 85.

The cause was a bone marrow disorder after a serious illness, according to his wife, Ann Charters.

Along with such musicologists as Alan Lomax and Harry Smith, Charters helped bring mainstream attention to once-obscure musicians from the South and Appalachia and make possible the blues revival of the 1960s. His first book, “The Country Blues,” came out in 1959 alongside an album of recordings by Johnson, McTell, Sleepy John Estes and others that reached a small but influential base of fans.

Bob Dylan would include a version of Bukka White’s “Fixin’ to Die Blues” on his debut album and later wrote a song about McTell. By the mid-’60s, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton and other rock stars were routinely performing blues songs.

“Sam Charters brought the country blues alive, and with great intelligence,” historian Sean Wilentz told the Associated Press. “His book was a touchstone at once enlightening and mysterious; the record, along with Harry Smith’s collection and a few others, was a thrilling informant.”

Charters, a native of Pittsburgh, moved to Scandinavia in 1970 to work as a producer for the Swedish record company Sonet Records.

A dual Swedish-U.S. citizen, he was best known for his books on the history of the blues and jazz, although his subjects also extended to Swedish fiddlers and poetry.

Early in his life, Charters became enamored of blues and jazz. In 1951, he moved to New Orleans and lived there for several years.

“He felt that the black musicians of New Orleans needed more recognition,” Ann Charters said in an interview with the AP.

His last book, “A Trumpet Around the Corner: The Story of New Orleans Jazz,” was published seven years ago.

In between, he published poetry and novels, produced records, and translated, among others, poems of 2011 Nobel literature prize winner Tomas Transtromer into English.

Among his nonfiction books was “The Roots of the Blues: An African Search” (1981), which documented his travels through West Africa studying the influence of the continent’s music on American blues.

“If Charters were not such a gifted writer, his book would be merely superb travelogue,” reviewer Ben Reuven wrote in The Times in 1982. “Charters is also a storyteller, a scholar, a sensitive observer of folkways and folk wisdom.”

Charters was born Aug. 1, 1929, in Pittsburgh and grew up there and in Sacramento. He served in the Army during the Korean War, then attended Tulane University in New Orleans and Harvard University before receiving his bachelor’s degree from UC Berkeley in 1956.

In 1959, Charters married his second wife, Ann, a leading authority on the Beat Generation who wrote the first biography of Jack Kerouac in 1973 and taught at the University of Connecticut. Together the couple was involved with the U.S. civil rights movement and became ardent critics of the Vietnam War.

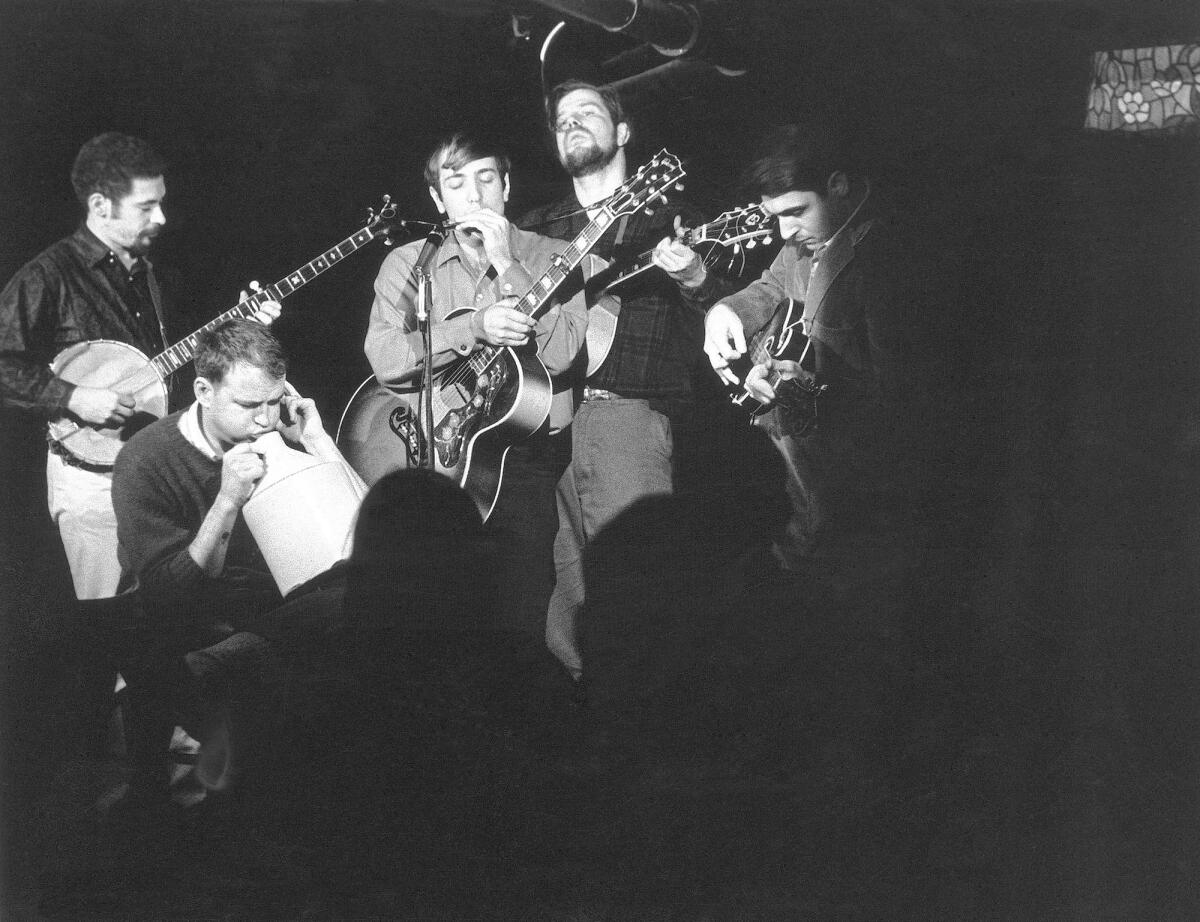

In the ‘60s, Charters produced albums by Country Joe and the Fish and the band’s anti-war hit “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag.”

Ann Charters said the couple became disillusioned with the U.S. political scene and in 1970 moved to Sweden, which she described as “a neutral country.”

His career continued in Sweden, where he became a respected figure among blues, folk and jazz musicians. He received Swedish citizenship in 2002.

His papers were donated to the University of Connecticut.

Besides his wife, Charters is survived by a son from an earlier marriage and two daughters.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.