Op-Ed: The president wants to ‘fast track’ two massive trade deals. Congress should slow him down.

President Obama is asking Congress to grant him trade promotion authority, the ability to “fast track” two massive trade deals with Europe and Asia: the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. This would allow him to pass those deals just as his negotiators will soon deliver them.

Fast track commits Congress to an up-or-down vote on whatever the administration negotiates, without the possibility of filibuster or amendments. It essentially excludes Congress from oversight and enables an efficient, executive-driven approach to international commerce. The purpose of this special treatment is to keep the House and Senate from inflicting death by a thousand cuts on delicate negotiating positions and specific concessions. Fast-track authority also bolsters the U.S. negotiating position with its foreign partners.

Most U.S. trade deals have been passed using fast-track authority, but the Asian and European partnerships under consideration now aren’t like the fast-tracked deals of the past. In significant respects, they’re not really trade agreements at all. Their new target is not trade tariffs but “behind-the-border” domestic regulations. Fast-tracking that kind of agreement would be a mistake.

Fast track was invented by President Franklin Roosevelt, and it became central to Depression-era trade policies and the liberalized post-World War II economic order. The original version of fast track allowed the president to enter into reciprocal deals that reduced tariffs within congressionally set limits. Congress pre-approved the broad terms of any agreement and otherwise delegated negotiating authority to the executive branch.

These trade policies — buoyed by fast track — were successful. Tariffs and export subsidies have mostly disappeared, except in the difficult and contentious case of agriculture. But instead of declaring victory, the trade agenda has become far more amorphous and consequential. What trade agreements now seek is to harmonize regulatory standards across countries. Fast track now serves a new purpose: not governance of trade but governance through trade.

The new agenda focuses on “non-tariff barriers,” first put on the table by the U.S. during international trade negotiations in the 1970s. A non-tariff barrier might be any national policy thought to be “trade-restrictive,” the idea being that such barriers constitute protectionism by other means — an indirect discrimination on the basis of national origin.

The U.S. endorsed the idea in part because tariffs were already so low that non-tariff barriers had become more important, but also because the success of trade liberalization had led to new competition from our European and Asian allies. Refocusing the agenda on non-tariff barriers allowed the United States to understand its declining competitiveness as the result of trade protectionism and not as a challenge to the idea of free trade itself.

The new agenda culminated in the trade deals of the 1990s, including the World Trade Organization and the North American Free Trade Agreement, which go far beyond tariff reduction. They include rules about industrial methods and production standards; environmental, health and social policies; intellectual property protections; the regulation of professional work; and the management of cross-border capital flows. The focus of such agreements is extremely ambitious: international policy convergence in support of global economic integration. In essence, the target of the new trade agenda is the kind of rules that make one national economy distinct from another.

Which brings us back to the two partnerships under negotiation now, TPP and TTIP. What the American public has seen so far of these agreements comes from leaks by concerned negotiators. On Wednesday, WikiLeaks released the Pacific deal’s chapter on investment, which appears to commit all parties to full liberalization of financial flows and the use of special arbitrators instead of normal courts. This will exacerbate concerns that public health, consumer advocacy, labor and environmental groups have already raised about previously leaked TPP chapters on intellectual property and the environment.

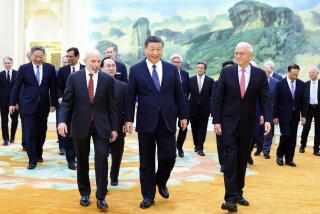

We know that the president has brought in industry groups — representatives of Big Pharma, Big Agriculture and Wall Street among others — to shape the closed-door negotiations, even though Congress is kept out. But congressional deliberation about these deals is not an obstacle to avoid; these policies are exactly what elected representatives should debate and decide. Alas, Congress is riven by partisanship and hamstrung by its extremes; it is widely and perhaps properly mistrusted. And yet Congress is the branch of government charged by the Constitution to represent us in our legislation. It is only through congressional oversight that ordinary Americans can participate in deciding “behind the border” issues.

Presidents may require the authority to negotiate tariffs and subsidies within limits, but the current negotiations go far beyond such concerns. Congress, for all its flaws, should not be allowed to exclude itself — and with it, the American people — from the process.

David Singh Grewal is an associate professor at Yale Law School, where he teaches international trade law.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.