Opinion: Justice Clarence Thomas dissents from a voting rights ‘victory’ in Alabama

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thomas says his colleagues are fixated on racial quotas instead of voting rights.

Civil rights groups cheered a decision this week in which the Supreme Court revived a lawsuit by the Alabama Legislative Black Caucus challenging the apportionment of the two houses of the Alabama Legislature.

The Black Caucus argued that the Republican-controlled Legislature “packed” more black voters into some districts than was necessary to ensure that African Americans in those areas had an opportunity to “elect the candidate of their choice.” As a result, there were fewer black voters in other districts, a state of affairs that improved the prospects of Republican candidates in those districts.

The Legislature’s defense was that it wanted to maintain pre-exiting black majorities in some districts lest they be accused of perpetrating a “retrogression” of black political influence.

Writing for a five-justice majority, Justice Stephen Breyer rejected that argument. He said that a lower court should take another look at the case to see if the 2012 redistricting plan involved any examples of unconstitutional “racial gerrymandering.”

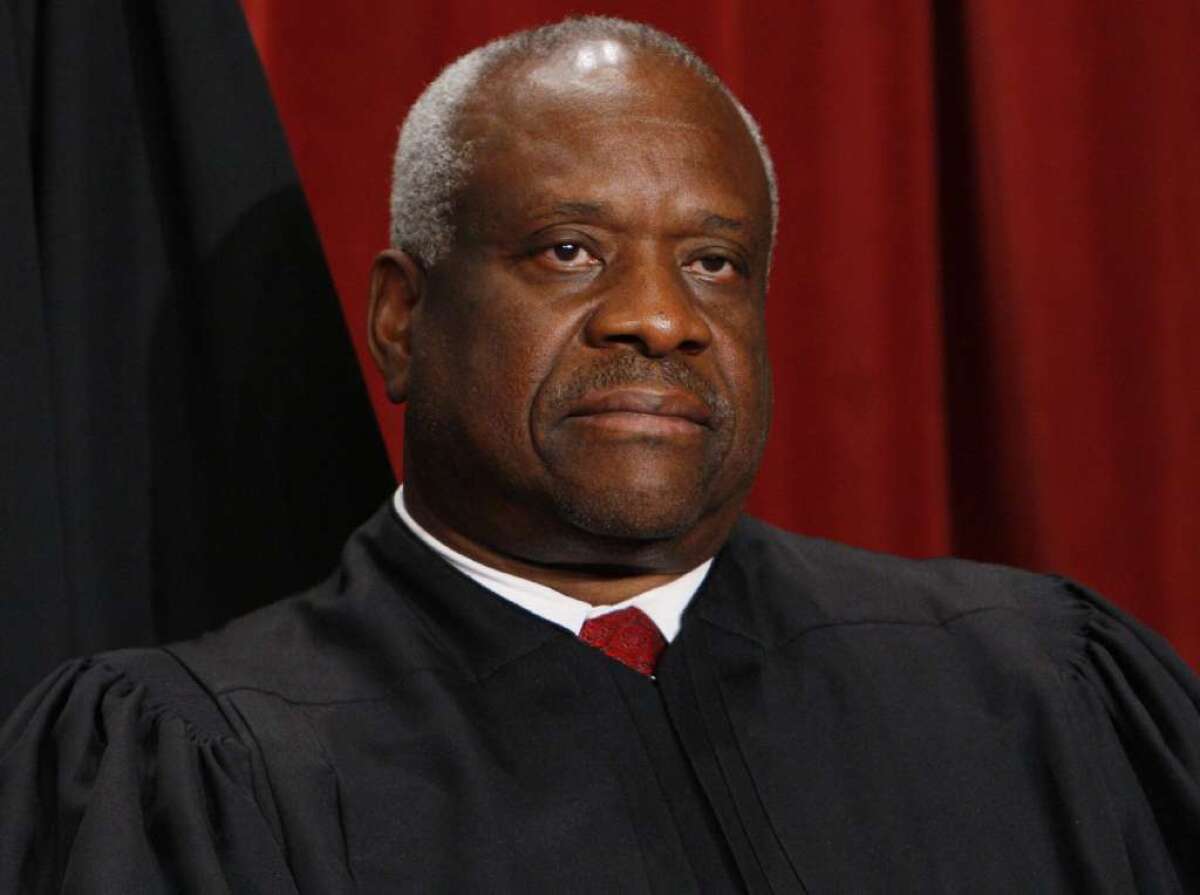

My colleague Timothy Phelps described the decision as “a rare victory for minority voting rights.” But the only African American member of the court, Clarence Thomas, dissented. He lashed out not just at the majority opinion but at a long line of decisions in which he said the court had forced states “to segregate voters based on the color of their skin.”

Thomas’ dissent is worth reading for this larger indictment of the court’s approach to voting rights, which has ranged far beyond eliminating restrictions on individuals’ right to vote -- the original rationale for the Voting Rights Act -- to ensuring that minority votes aren’t “diluted” in the drawing of district lines for Congress and state legislatures.

Thomas said that states “have been whipsawed, first required to create ‘safe’ majority-black districts, then told not to ‘diminish’ the ability to elect, and now told they have been too rigid in preventing any ‘diminishing’ of the ability to elect.”

Instead of focusing on the right to vote, Thomas said, his colleagues were fixated on figuring out what the “correct” racial quotas should be. As a result of this week’s decision, states would be forced to “analyze race even more exhaustively, not less, by accounting for black voter registration and turnout statistics.”

This isn’t a new position for Thomas, and it’s related to his skepticism about racial quotas in other contexts, such as affirmative action in higher education. If the Constitution is color-blind, states shouldn’t be in what Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. once called the “sordid business [of] divvying us up by race.”

In the apportionment context, color-blindness would mean that legislative districts would be designed on the basis of compactness, contiguity and a respect for municipal boundaries -- but never, ever on the basis of race.

The counter-argument, of course, is that, given America’s racial history, it’s natural that racial minorities seek to be represented by legislators who aren’t just attuned to their interests but who look like them. Someday the “black vote” may be as anachronistic a concept as the “Catholic vote,” but that day hasn’t arrived. Meanwhile, it’s appropriate for courts to ensure that the “black vote” (or the “Latino vote”) isn’t diluted.

But even if you think that sort of fine-tuning is beneficial, Thomas’ opinion demonstrates that it comes at a cost.

Twitter: @MichaelMcGough3

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.