Review: Roz Chast wryly recalls her elderly parents in a graphic memoir

There’s an image a few pages into “Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?” whose layout will be familiar to anyone who’s seen Roz Chast’s cartoons before: a scritchy little figure is surrounded by a handful of sly little captions addressing different half-formed perspectives. (“My mother referred to the entire episode as ‘that mess’”). The image is, in fact, a drawing of Chast’s prematurely born sister who lived only for a day — and Chast’s gift for comedic pacing, applied to her tentative understanding of a tragedy, brings out a much bleaker, bitingly self-aware kind of comedy.

That’s the ingenious trick of perspective that drives Chast’s memoir of her parents’ slow decline and death, presented partly as comics and partly as handwritten prose. There’s no experience that’s both more awful and more universal than the stumble toward the grave; there’s nothing funny about it in itself. But the human capacity for denying it (and, in particular, George and Elizabeth Chast’s extraordinary appetite for denial), and the little indignities scattered along the way, are exactly the kind of folly that fuels her best comedy.

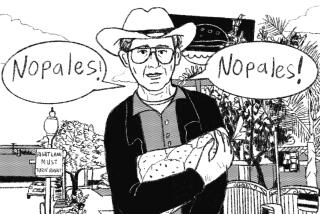

Chast’s cartoons are among the reliable pleasures of the New Yorker: jittery, acerbic and finely observed, they slice to the bone of a certain kind of high-strung East Coaster. Her knack for letting characters reveal mountains about themselves in a few words shows up even before the first page, as her parents bicker neurotically about the table of contents they find next to them. Her father is as twitchy about it as he was about anything unfamiliar; her mother reassures him with a nonsensical rhyme — “stop getting nervous in the service” — and advises him to make some tea with a used tea bag that Chast draws, soggy and cold, on a little saucer: “it still has plenty of juice in it.”

The story proper begins with an account of Chast’s 2001 visit to her octogenarian parents’ house for the first time in more than a decade. It became clear over the next few years that their situation wasn’t sustainable in the long term — they were getting far too old to take care of themselves — but they also didn’t want to make a deliberate change in the routine they’d had as a couple for decades, quarrels and all. They also refused to confront the reality of their failing bodies, because that always seemed to be followed by unspeakable horrors.

In one scene, Elizabeth tells Roz of a couple who signed their money over to their daughter: “Next thing you know, she puts them into a nursing home ... and she buys a drawerful of cashmere sweaters!” (This last is accompanied by a shift to one of the rageful facial expressions that make regular, hilarious appearances in Chast’s cartoons.)

Their stubbornness is funny until it becomes catastrophic. Elizabeth falls repeatedly and refuses to go to a hospital; George, his memory failing, frets constantly about a bunch of ancient bank books. (A drawing of them is grimly hilarious in its own right: There’s a mass of them, large and tiny, their pages fluttering open, with names like “Scrimp ‘N’ Save” and “You Never Know Savings Bank.”) The bank books are a pointed symbol: As Chast discovers when her parents finally do move to a retirement home (“the Place”), elder care is hellaciously expensive, and it gets only more so after her father dies and her mother requires full-time care. That’s another unpleasant subject that she forces herself to face, although it’s harder for her to be funny about that.

Unsurprisingly, family history bubbles up throughout the book and especially in its second half — unresolved, powerful feelings are always fuel for Chast’s cartoons, and her drawings of her Russian-immigrant paternal grandmother Katie practically rumble with a mixture of viciousness and compassion. At the bottom of that page is the brutal payoff: “She died in 1972. In a Place.”

Chast manages to find things to wisecrack about in some really unlikely spots: She punctuates her discussion of her mother’s understandable depression over wearing a do-not-resuscitate bracelet with a drawing of her in a tourist-style ensemble of DNR T-shirt, bag, hat and umbrella, captioned: “Limited time offer! Not available in stores! Get the entire ensemble!”

A few times, Chast shifts away from her gleeful cartooning to reproduce things to which its tone couldn’t do justice: photographs of the clutter her parents left behind in their apartment when they moved to a retirement home and, at the end of the book, the somber drawings she made of her mother immediately after she died. Fair enough — but there’s genuine tenderness beneath her scribbled, glowering caricatures, and turning her family’s slow disaster into gallows humor is clearly an act of love.

Wolk is the author of “Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean.”

Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?

A memoir

Roz Chast

Bloomsbury: 240 pp., $35

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.