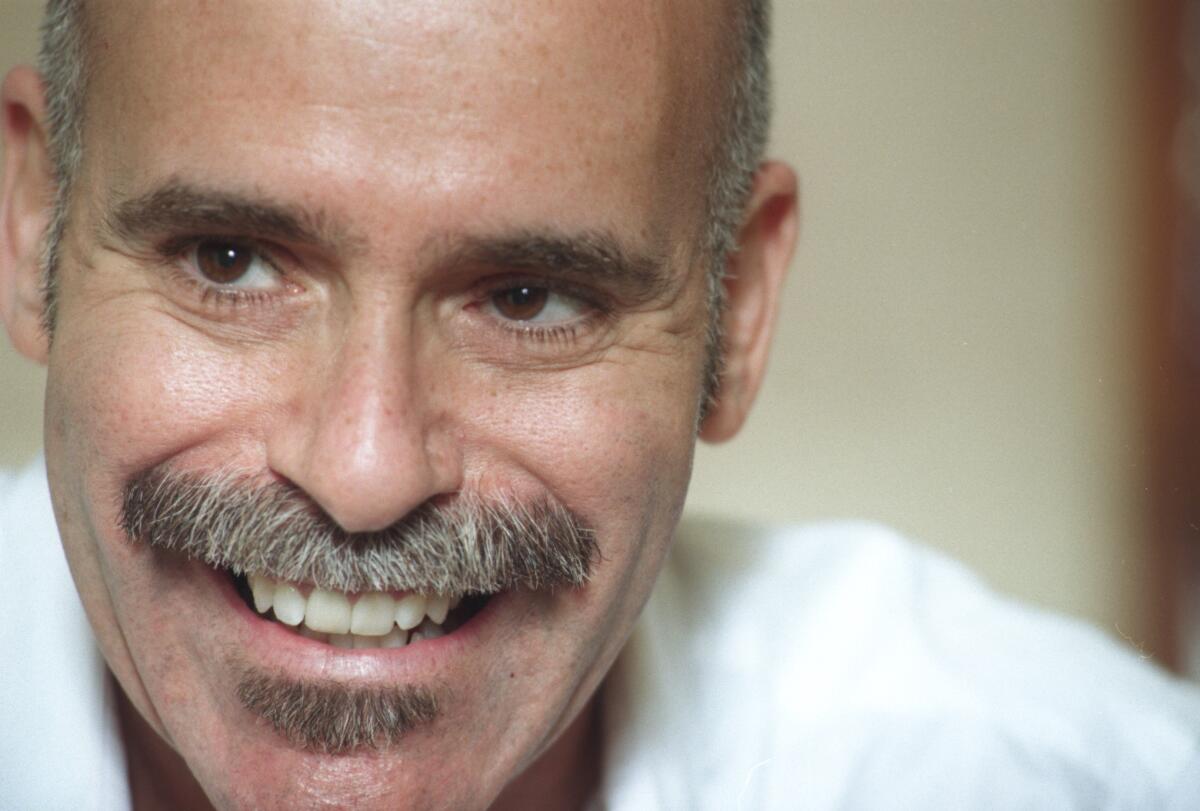

Bernard Cooper’s portrait of the artist as a young man

In the current issue of Granta, Bernard Cooper publishes an excerpt from his memoir “My Avant-Garde Education,” which is due out next year.

Cooper, of course, is a memoirist and fiction writer (“Guess Again,” “The Bill From My Father”) of uncommon subtlety and nuance, who uncovers in the quietness of personal experience the tumult of being alive. Born and raised in Los Angeles, he’s a quintessential local voice, working from out of what D.J. Waldie calls our “sacred ordinariness,” portraying the city not as mythic landscape but as a place where people live.

If you don’t think that’s radical, you might want to think again. Along with Waldie, Wanda Coleman, Susan Straight, Eloise Klein Healy and a handful of others, Cooper is one of the writers responsible for developing a Southern California aesthetic, in which what’s most vivid about the place is everything we might take for granted somewhere else. Work, family, education, sexual and personal identity: This is the substance of his writing, along with a fine-grained eye for observation, a way of seeing situations as they are, not as he wishes they might be.

All of that marks “My Avant-Garde Education” — or at least the section that appears in Granta. Unfolding in New York, where Cooper lived briefly as a student at the School of Visual Arts (he later transferred to Cal Arts), it portrays his creative awakening on the first day of a class taught by the conceptual artist Vito Acconci, who confounds his students by assigning them to “bring in nothing,” and then refuses to explain further, insisting: “Is it the artist’s job to answer questions, or to ask them?”

For Cooper, this was a transformational event. “In a classroom in Manhattan on a rainy day,” he confides, “my perception of art was changed forever. Vito Acconci’s pedagogy was a mixture of persistent enquiry, faith in the invisible and nudges toward the unknown. It struck me for the first time that art might exist beyond the realms of painting and sculpture. This was a mind-boggling revelation, like opening a door in your own house and discovering an entirely new room. My jaw went lax, my breathing deepened. The spirit of conceptualism had entered me, and I became a convert then and there.”

And yet, for all the revelation implied by such a moment, Cooper remains confused and unfulfilled in other ways. Unable to come to terms, or even express, his sexuality, he lives in a shadowy half-world, terrified he will somehow reveal himself as gay while also longing for the men he sees on the street.

This theme recurs throughout his work, most notably in his 1996 collection “Truth Serum.” The title essay deals in part with this same period, tracing a relationship Cooper had with a woman, while “Burl’s” evokes the confusion of a young boy discovering that the line between men and women is not as clear-cut, as distinct, as he had thought.

“My Avant-Garde Education” tracks a similar set of ambiguities but takes them further, exploring the questions raised not just by life but also by the pursuit of art. Is it possible for creativity to redeem us? Can we declare ourselves in some essential sense not only in what we do but also what we make?

Late in the excerpt, Cooper comes face-to-face with this conundrum, when he backs away from his sexuality in a class assignment; the closest he can get is to acknowledge, “Sometimes I’m afraid.” Such a statement, he tells us, “manages to touch on the truth without actually jarring it loose.”

Is this, then, a missed opportunity or a first step? Cooper doesn’t say. But what “My Avant-Garde Education” means to tell us it is that in his reticence, his fear of exposure, Cooper plants the seeds of real expression, that the experience, and the education, cut both ways.

ALSO:

Shelley Jackson’s winter’s tale

The last word on the Holocaust?

The David Cronenberg-Kafka connection

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.