Julia Wertz excavates herself

Over at narrative.ly, Julia Wertz has an essay, “The Fart Party’s Over,” about her struggles with alcohol and depression, which is also, in part, the subject of her 2010 book-length comic “Drinking at the Movies.”

“The Fart Party” is the name of Wertz’s autobiographical comic strip – humorous, self-lacerating – and, among other things, the essay explores the limitations of the persona it imposed. “During the height of my career thus far (2009 to 2010),” Wertz tells us, “I found myself living the classic double life of appearing well in public but going to hell in private.”

To evoke that experience, she interweaves short prose passages with art “taken from three different sources: 1) A completed, yet unpublished book about my alcoholism, 2) sketchbook diaries I made while bottoming out, and 3) pages from ‘The Infinite Wait and Other Stories,’ the first book I ever made while sober.” The result is a fascinating hybrid, as well as a telling glimpse into Wertz’s process, and a meditation on how art gets made.

Wertz has always been self-revealing; “Drinking at the Movies” opens with her coming “to consciousness at 3 a.m. in a twenty-four-hour laundromat in Brooklyn, New York, eating Cracker Jacks in my pajamas,” the tail end of a drinking binge. In her narrative.ly essay, however, she takes us inside the process, teasing out the relationship between her life and her work.

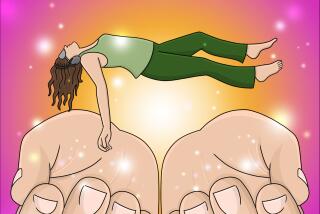

“The way I presented myself in comics,” she writes, “was in a cartoony style, with short black hair and bug eyes. It was a style I’d settled on years ago, based on a hairstyle I had once, for about two weeks. I chose the style quickly, without much thought, but perhaps I subconsciously did it to separate my real self from my cartoon self. My cartoon self made my problems seem funny, but when I drew my real self in secret diary comics, the tone and style was completely different and much more reflective of the truth during that year.”

To make the point explicit, she sandwiches this passage between two very different types of visual material: first, a sequence, featuring her comics alter ego, that takes us through all the stories she told herself to justify her drinking, and then a series of sketchbook pages, impressionistic and full of longing, the “secret diary comics” to which she refers.

“I don’t keep mirrors in my studio,” she writes above two incidental self-portraits, “and when I catch a glimpse of myself in the window, I’m surprised at how young I look … as though I expect a much older face to be looking back.”

The effect is tentative -- fleeting, almost -- as if the artist herself were shell-shocked.

Eventually, Wertz ended up in rehab, which she describes in a letter as “like a mad day at summer camp except for the part where it never stopped sucking.” Her willingness to reproduce these bits and pieces is what makes her essay so moving, with its implication that she is holding nothing back.

This, of course, is part of the point, and the illusion; as she told me in a 2012 email interview: “I’m very careful about what I present and what I leave out. I omit a lot. I’ll let the reader into my head for a while, which seems very intimate and confessional, but then I’ll leave out huge chunks of time or difficult experiences I don’t want the public to know.”

And yet, in the interplay here between art and writing, between more polished work and the rawness of her correspondence and her sketchbooks, Wertz has taken autobiography to a different level, where it is the questions, rather than the answers, that resonate.

Like many other people, she has struggled to maintain her sobriety, and struggled even more to remain engaged. After the publication of “The Infinite Wait” in 2012, she “put away all my drawing supplies” and became an urban explorer, investigating derelict buildings such as the Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in Morris Plains, N.J., which she has also written about for narrative.ly.

“I am still a cartoonist, don’t get me wrong,” she writes late in her essay, but the larger point is that she has come to some sort of (open-ended) accommodation with herself.

“So the question,” she asks, “that probably didn’t cross your mind until I put it there is, if I’m happy and healthy, does it have a negative effect on my comedic work? And the answer is that I don’t know.”

ALSO:

Shelley Jackson’s winter’s tale

Imagining Borges’ ‘Library of Babel’

In ‘Dockwood,’ a geography of tiny images

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.