Q&A: Junot Diaz on reading, writing, and America’s amnesia about race

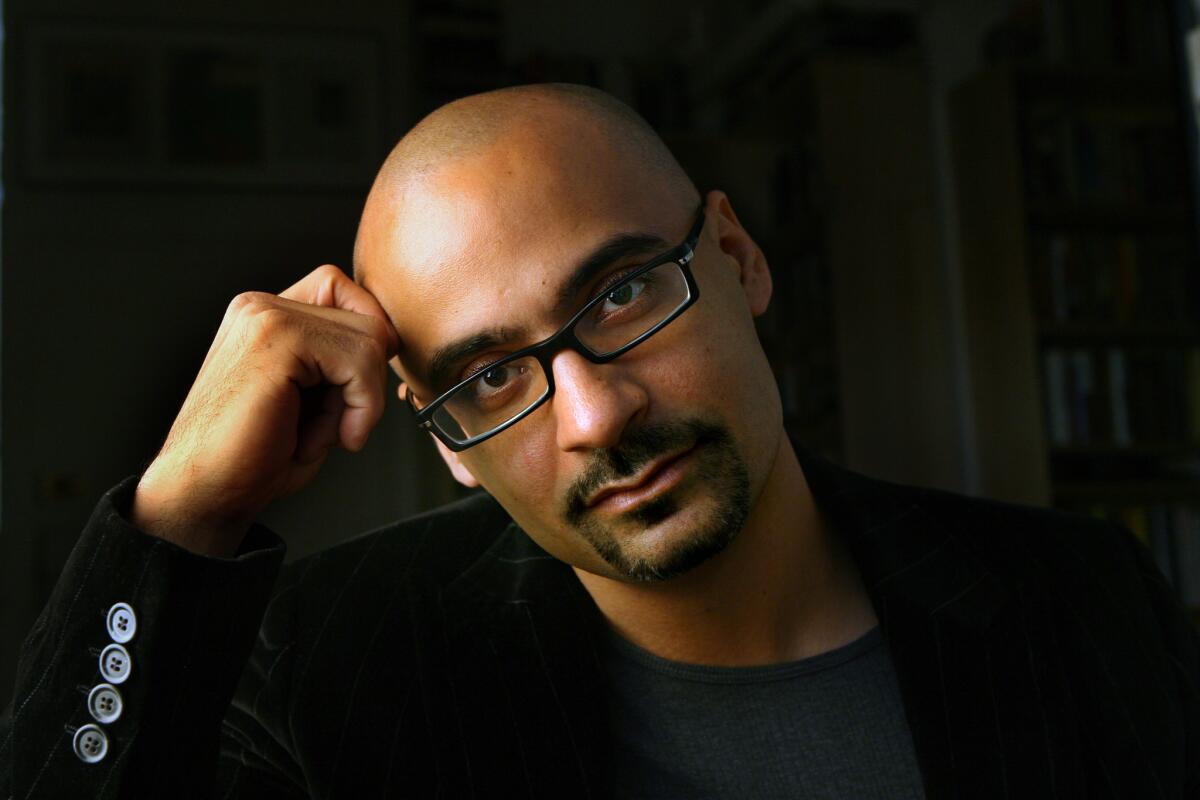

Pulitzer-Prize-winning author Junot Diaz.

When Junot Diaz published “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao” in 2007, fans had been waiting almost a decade since his stellar debut, the short story collection “Drown.” The wait paid off: “Oscar Wao” was a wildly engaging novel about a Dominican teen in New Jersey. The novel hit bestseller lists and scooped up a heap of literary awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Diaz followed that up with a number of short stories published in the New Yorker and later in the 2012 collection “This Is How You Lose Her,” a National Book Award finalist.

Now a writing teacher at MIT, the Dominican Republic-born, New Jersey-raised Diaz doesn’t make it to the West Coast very often. He’ll be visiting Occidental on Tuesday at 7 p.m. to read from his work, which he’ll discuss with writer Danzy Senna. The event is free and open to the public.

Diaz categorizes his stories in different ways -- “family loss,” “masculine stupidity” -- but hasn’t yet decided what he’ll read. As a frequent presenter of his work, Diaz says he waits until the last minute, wanting to get a feel for the room and the audience.

A reading is always going to be just a slice of a novel or an excerpt of a short story. When you’re reading, how do you give people a sense of the scope of the complete work of fiction?

The idea is that there is no replacing the experience of reading a text. The very private interaction, the intimate communion of reading, sitting down with a book, living with it, having the book dwell inside of you -- there is no substitute for that. Writers, when we’re in the public, we’re sort of ambassadors for our books. I think that the idea is that you attempt to re-create a much more simple version of the concerns and aesthetic work that your book is doing. ...

For me, when I do a reading or a public presentation, I feel like I’m there as an advocate of reading, that kind of magic that comes out of reading. The life of the mind, and the sympathetic practices, the imaginative practices, and the literary and linguistic textual practices that reading evokes.

It’s also an opportunity and an excuse to come into contact with readers. That’s the one thing that usually happens at a reading for me; it’s this convocation of what I would call my nation. These are the people that I feel most identified with. I don’t feel organically identified with writers; I feel I am a reader. For me being around other readers and talking about reading and talking about the love of books is very natural. I sometimes think I became a writer as a pretext of being a full-time reader.

Tell me something you’re reading now that you like very much.

I’m reading this book called “Poetic Justice: The Literary Imagination in Public Life” by Martha Nussbaum [1996]. ... Terrance Hayes’ “How To Be Drawn” [2015]. I’m re-reading Natalie Diaz’s “When My Brother Was an Aztec” [2012] -- that book’s a killer. That is not to be missed.

Last year you wrote a widely-discussed essay criticizing creative writing MFA programs for lacking diversity and for their students being blind to “race as a lens.” Do you think that our culture is now more openly discussing race, with wider reporting of police violence and the Black Lives Matter movement?

I think that, as a country, Black Lives Matter more than amply showed we have great difficulty in dealing with the effects and the legacy of white supremacy. It’s not something that as a nation we’ve ever handled well. ... Certainly those of us who were trying to have this discussion are showing an enormous amount of leadership and an enormous amount of courage pushing this stuff forward. A lot of the new generation is doing a tremendous amount of work; the people who sparked the Black Lives Matter movement are women for the most part, people without a lot of institutional power.

But the pushback is extreme. And I think that we’re in another moment where historically, periodically issues of race and the kind of panorama in which we live becomes more clear and comes into focus. But we also historically have a great habit of allowing these moments to dissipate; for the landscape to become murky; for the conversation to slip away. Our amnesia around this and our ability to change the subject is really unmatched.

Twitter: @paperhaus

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.