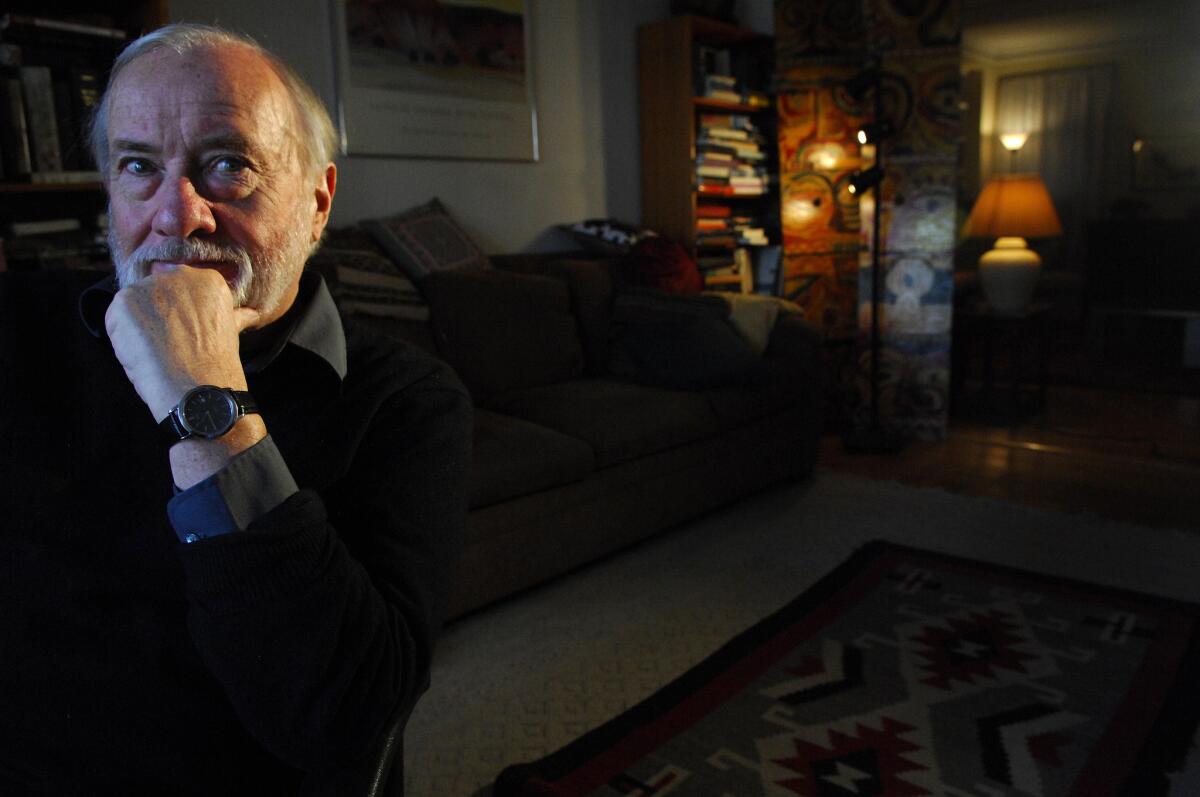

Remembering Robert Stone

Robert Stone was not a joiner. This may be what I admired about him most. During the 1950s, while living in Manhattan, he moved around the edges of the Beat scene (his wife, Janice, worked at the Seven Arts, a Times Square coffee shop and Beat hangout); by the early 1960s, he had relocated to Northern California, where he was part of a Stegner Fellow cohort at Stanford University that included Ken Kesey, Larry McMurtry and Tillie Olsen — and one of the early acid pilgrims in Kesey’s circle, from which the Merry Pranksters would arise.

And yet, for all that this signals a certain engagement, the novelist — who died Saturday at 77 of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — spent much of the last half century standing willfully apart.

“The difference between a lot of those guys and me,” Stone told me in a 2003 interview, referring to his contemporaries in the counterculture, “was that many of them came from solid Western farms, where the questions were all pretty well answered, and they were answered with no talking back. So they were ready to rebel. My situation was very different.”

The same might be said of Stone’s characters, who together form a rogue’s gallery of late American alienation and ennui. There’s Rheinhardt, protagonist of his 1967 debut “A Hall of Mirrors” — a musician turned drifter who ends up working for a right-wing radio station in New Orleans. Or Ray Hicks and John Converse of the National Book Award-winning “Dog Soldiers” (1975), whose scheme to smuggle three kilos of heroin from Vietnam to California goes bleakly, if inevitably, wrong.

To read these books, as I did, in the late 1970s was like coming across some sort of potent tonic. No flower power, no Summer of Love propaganda, just the long, inevitable collapse of 1960s idealism into a more general condition of paranoia and decay.

In his 2007 memoir “Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties,” Stone frames this through the most personal of filters: “Curved, finned, corporate Tomorrowland, as presented at the 1964 world’s fair, was over before it began, and we were borne along with it into a future that no one would have recognized, a world that no one could have wanted. Sex, drugs, and death were demystified. The LSD we took as a tonic of psychic liberation turned out to have been developed by CIA researchers as a weapon of the cold war. We had gone to a party in La Honda in 1963 that followed us out the door and into the street and filled the world with funny colors. But the prank was on us.”

That kaleidoscopic sense of (anti-)destiny had its roots in Stone’s upbringing; born in Brooklyn in 1937, he was abandoned by his father as a young child and spent 2 1/2 years, until he was 8, in a Marist brothers orphanage after his mother was diagnosed with schizophrenia. “I had a lot to lose,” he told me. “I was scared of chaos.”

Chaos became Stone’s lingua franca — politically and cosmically. His vision was fiercely moral and fiercely unrelenting, not unlike that of Conrad or Dostoevsky, defined by the sense that God is an emptiness with which we must continually contend.

“Oh Frank, you lamb,” says the main character of his 1996 short story “Miserere,” to a priest who refuses to bury the unborn fetuses she has stolen from an abortion clinic, “what did your poor mama tell you? Did she say that a world with God was easier than one without him? … Because that would be mistaken, wouldn’t it.”

What Stone meant is not that God does not exist, but that God created the universe and then moved on. “I feel a very deep connection to the existentialist tradition of God as an absence — not a meaningless void, but a negative presence we live in terms of,” he told the Paris Review in 1985.

Such a perspective is hard to refute, living, as we do, in a world of random violence, military rhetoric and terror attacks. It underlies a number of Stone’s novels — not only in “Dog Soldiers” but also 1981’s “A Flag for Sunrise,” and the magnificent “Damascus Gate” (1998), which is, I want to say, his masterpiece, an epic work of fiction that frames Jerusalem as millennial proving ground.

Mostly, though, I think about his characters, alone in a universe that is not so much malevolent as indifferent to their concerns. This is the ethos of “Under the Pitons,” collected in his 1997 book of short fiction. “Bear and His Daughter,” in which two couples, running dope to Martinique, go swimming off their boat in calm waters, only to discover, too late, that no one has put a ladder down.

Stone’s work, it must be said, tailed off after “Damascus Gate”; his 2003 novel “Bay of Souls” is superficial, overblown, while “Prime Green” reads as oddly second hand. He made a return to form, however, with his last novel, 2013’s sharp and moving “Death of the Black-Haired Girl.”

There, he uses a campus abortion debate to evoke characters driven by “an ancient anger … a sense that [they] had been born out of line, raised wrong, lived deserving of some unknowable retribution that it was [their] duty and honor to face down.”

The reality, of course, is that we live with the threat of this retribution every day, every moment, which means that we are all fundamentally outsiders — a state that Stone, as powerfully as any writer I can think of, understood.

Twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.