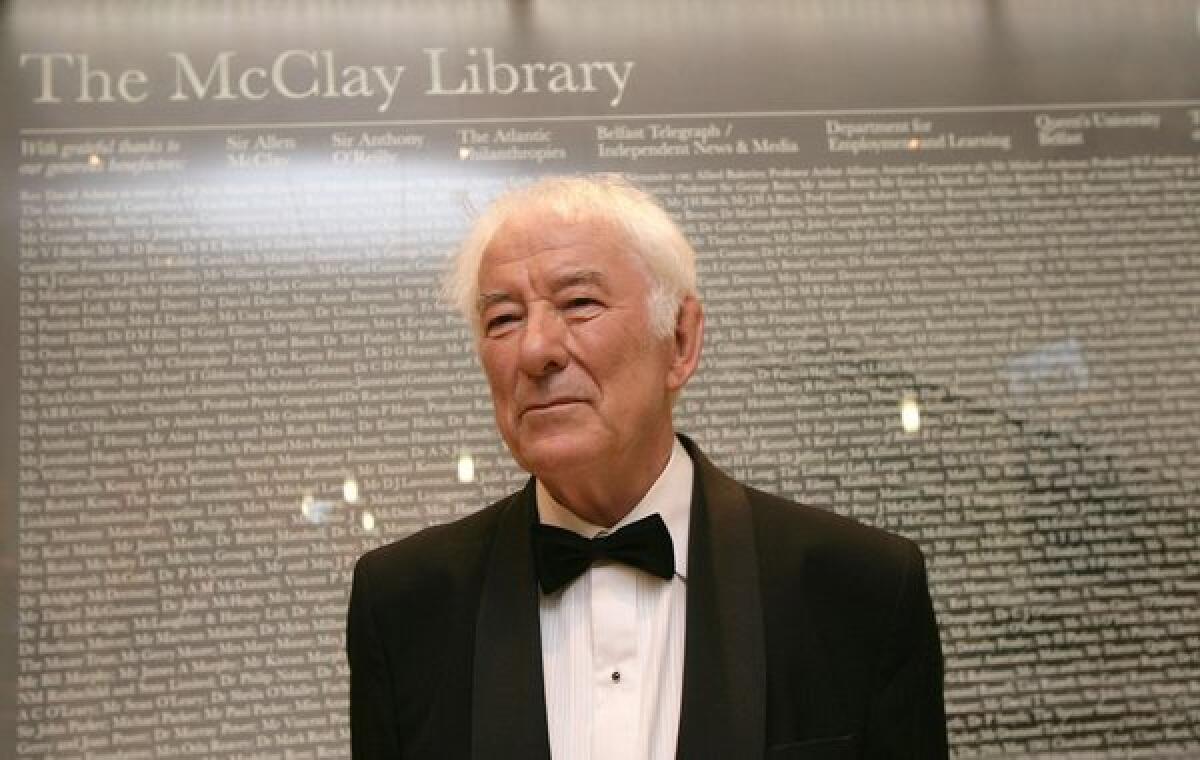

Seamus Heaney, Nobel Prize-winning poet, has died

Seamus Heaney, the poet and essayist from Ireland who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1995, has died. He was 74.

An Irish Catholic who was growing up in Ulster when the Troubles began and who later moved to Dublin, Heaney engaged with the violence in Northern Ireland, sometimes through history and myth, exploring the conflicting emotions it raised. “We lived deep in a land of optative moods, / under high, banked clouds of resignation,” he wrote in “From the canton of expectation.”

The Nobel committee cited Heaney’s “works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past.”

After winning the Nobel, Heaney’s work broadened in scope. In his 2001 collection “Electric Light,” the L.A. Times said, “The echoes of the prehistoric past, classical mythology and Celtic mysticism have been sounded without any loss of immediacy: Heaney’s capacity for capturing sensory experience is undiminished.”

Heaney talked about poetry with Chinese writer Bei Ling in the 1990s. “The form of expression which we call poetry always involves memory, some sense that a sacred truth is being kept for us, some sense of a civilization having been won, and then valued and then made alive again each time.”

Later in the interview, Heaney addressed the language of poetry. “What goes into our poems and how do we write? Where does the sound come from? Does it come from previous poetry we have read? Partly. Stanzas, rhythms and meters are part of our formation and so there is the inclination to repeat those tunes. But then there are the sounds we make as biological creatures, creatures of our habitat, our grunts and yells and mating calls, you know, our equipment of barks and moos. Poetry is also involved with those primal speech acts. Robert Frost was very wise about these matters; he said that in poetry we hear what he called the “sound of sense.” If you are listening through a wall, for example, and hear a conversation going on, you can understand from the sound they are making whether it’s argument or intimate conversation or desultory chat or whatever. Even if you don’t hear the content of the speech, the posture of the voice is making sense, suggesting meaning. I am a firm believer in the undergraph, the graph as it were of our intent to speak. That is very important in poetry, in the cadences, in what affects the listener. It lets the thing be H-E-A-R-D.”

In the L.A. Times, critic Richard Eder wrote of his work, “He employs poetry’s power to tell truth, and the artist’s power to make us know that it is a truth we need. His poems, elegant fountains, are also water; we realize it and grow thirsty.”

Ultimately, Heaney will be remembered for his poetry, like 1972’s “Gifts of rain”:

I

Cloudburst and steady downpour now

for days.

Still mammal,

straw-footed on the mud,

he begins to sense weather

by his skin.

A nimble snout of flood

Licks over stepping stones

And goes uprooting

he fords

his life by sounding.

Soundings.

II

A man wading lost fields

breaks the pane of flood:

a flower of mud -

water blooms up to his reflection

like a cut swaying

its red spoors through a basin.

His hands grub

where the spade has uncastled

sunken drills, an atlantis

he depends on. So

he is hooped to where he planted

and sky and ground

are running naturally among his arms

that grope the cropping land.

III

When rains were gathering

there would be an all-night

roaring off the ford.

Their world-schooled ear

Could monitor the usual

confabulations, the race

slabbering past the gable,

the Moyola harping on

its gravel beds:

all spouts by daylight

brimmed with their own airs

and overflowed each barrel

in long tresses.

I cock my ear

at an absence -

in the shared calling of blood

arrives my need

for antediluvian lore.

Soft voices of the dead

are whispering by the shore

that I would question

(and for my children’s sake)

about crops rotted, river mud

glazing the baked clay floor.

IV

The tawny guttural water

spells itself: Moyola

is its own score and consort,

bedding the locale

in the utterance,

reed music, an old chanter

breathing its mists

through vowels and history.

A swollen river,

a mating call of sound

rises to pleasure me, Dives,

hoarder of common ground.

ALSO:

Finding lost Philip Roth in a Provincetown used bookstore

Randall Kennedy targets affirmative action in ‘For Discrimination’

Sexual assault allegations are filed against Amazon Publishing head

Carolyn Kellogg: Join me on Twitter, Facebook and Google+

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.