Book Review: ‘An Ideal Wine’ by David Darlington

An Ideal Wine

One Generation’s Pursuit of Perfection — and Profit — in California

David Darlington

Harper: 356 pp., $26.99

The California wine business is full of contradictions. Little wonder.

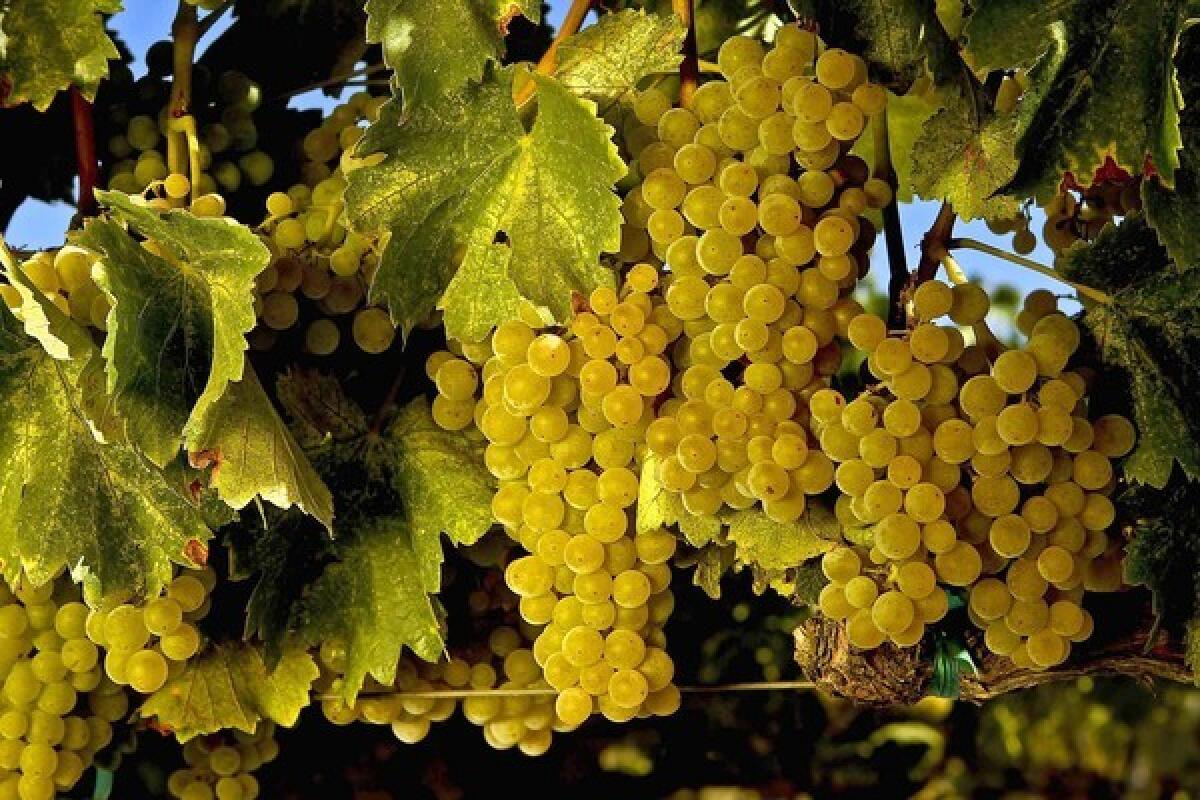

On the one hand, the industry cultivates an image of wine being an almost accidental beverage, a product of a munificent nature that takes ripe fruit from sun-dappled vineyards and somehow, magically, transforms it into a liquid symphony that can ennoble not only those who consume it but also those who make it.

On the other, it is a ruthless, cutthroat business, one that accounts for more than $18 billion in sales every year — 80% of which goes through fewer than a dozen large corporations. And as important as the image of a rustic vigneron might be, the specialty equipment and chemical enhancements used in most modern wineries are capable of spinning neutral grape juice into salable product.

This is the radically separated right-brain, left-brain world described so ably by David Darlington in “An Ideal Wine,” one of the best books written about how modern wine is really made and sold.

Darlington is a fine reporter and writer whose earlier books have covered subjects as varied as the Mojave Desert and Area 51. He previously assayed the wine world in “Angels’ Visits,” which pondered the mysteries of Zinfandel. In this book, he approached wine more from the point of view of a besotted admirer. Now, 20 years later, his gaze is a little more distanced and his appreciation a lot more nuanced.

This is not at all to suggest that “An Ideal Wine” is a tell-all screed. One of Darlington’s strengths is that he is able to pull back the curtain on the wine business without ever losing sight that the beverage itself is capable of great magic. He takes us into the worlds of utterly opposite wine figures — or so it seems.

The first is Leo McCloskey. He is Mr. Left Brain: His influential company, Enologix, claims to be able to predict critical scores and potential sales for wines based strictly on a chemical analysis of the grapes — even while they are hanging in the vineyard.

Has there ever been a more right-brained winemaker than Darlington’s other subject, Randall Grahm? One shudders to think. The founder of Bonny Doon Vineyard, originally in the Santa Cruz Mountains, Grahm plays the vinous butterfly, flitting from here to there, dabbling in hermetic biodynamic practices, inventing new wines from old, underappreciated grapes, and selling them all through marketing materials that can best be described as Mad magazine meets Jacques Derrida. (Of course, underlying this seemingly quixotic nature is a canny salesman who pushed Bonny Doon to produce as much as 450,000 cases a year at its peak, making it one of the couple of dozen biggest wineries in the country.)

It does become fairly clear that Grahm is the subject who captured Darlington’s heart — is there a wine writer so cold he has not been seduced by Grahm’s magic? He’s the smartest, funniest, most introspective and, quite often, wisest geek you could ever hope to meet.

But the book’s core strength is the way Darlington is able to regard both characters sympathetically without ever falling for either’s shtick. This is true whether he is describing McCloskey’s proprietary calculations that turn esoteric measurements of an immature grape’s tannins, flavonoids and other chemical compounds into predictions of potential sales, or Grahm’s penchant for biodynamic “crystallizations” that purport to show “wine’s degree of connectedness to the soil, to its organizing and growth forces.”

Surprisingly, the two winemakers seem pretty close on the existential wine question of the existence of terroir (the notion that the flavor of a wine can reveal a sense of the place where the grapes were grown, often derided as touchy-feely by analytic winemakers). For Grahm, this is the be-all, end-all of his wine quest. And, it seems, McCloskey is sympathetic — to a point. After all, his doctoral dissertation was in chemical ecology, based on the idea that plants change chemically in response to the areas in which they live. In the end, then, it seems that McCloskey and Grahm — whose approaches seem so different — may have more in common on some key points than you (or they) might have expected.

Still, the two are on different planets when it comes to terroir’s necessity, or even desirability, in a fine wine. Given the choice between gobs of jammy ripe fruit and a mineral-laden sense of place, it’s easy to predict which each man would prefer.

On a more fundamental level, though, they also seem to agree on wine as a metaphor, though for starkly opposing world views. For Grahm, wine at its best allows the sensitive taster to glimpse the hidden workings of nature, to revel in unseen connections and to better understand his place in the universe. For McCloskey, to be at its best, wine requires the skilled technician’s ability to transform the imperfect raw materials nature provides into a product that gives pleasure to the masses (and income to its producers).

To really understand California wine today, you have to be able to hold both ideas in your head at the same time. Is it any wonder, then, that winemakers seem so eccentric?

Parsons is The Times’ food editor.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.