Book review: ‘Caribou Island’ by David Vann

Caribou Island

A Novel

David Vann

Harper: 296 pp., $25.99

“Caribou Island” is disturbing, as dark as it is moving, powerful far beyond the dimensions of many debut novels. The book focuses tightly on a small group of characters. If you’ve read the stories in David Vann’s “Legend of a Suicide” or his “A Mile Down: The True Story of a Disastrous Career at Sea,” you may recognize some of them. And as in his previous books, Vann ranges over the landscape of his childhood: the cold rain forest of Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula, the ocean, fishing vessels, storms, narcissism, suicide.

At the center of the novel is Irene, a recently retired preschool teacher. Vann’s compassion for her — as she writhes from the pain of a headache with no identifiable source and the pain of a frayed 30-year marriage — is weighty from our first glimpse of her.

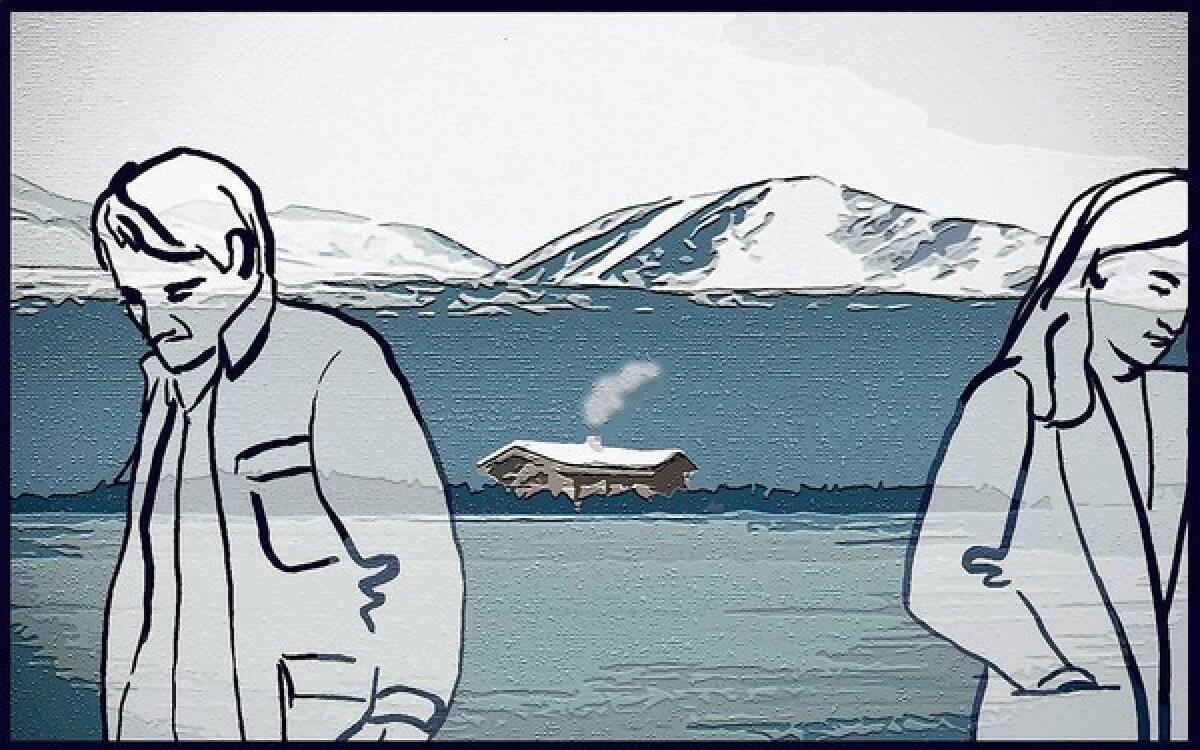

Consumed with rage, Irene helps her husband, Gary, in his latest “impossible project,” to build a small cabin that is to be their new home on a small island in Skilak Lake. They work side by side, though emotionally miles apart. Gary is a UC Berkeley dropout from the medieval studies program who in his 20s went to Alaska in pursuit of a frontier life. He is impatient and confused by Irene’s anger; he’s a “champion of regret” who can’t shake the feeling that he’s been cheated.

Though there have been no specific transgressions, Irene’s disappointment with Gary is acute. Her bitterness is ugly, but her condemnations are mostly true. “He can’t take care of anyone except himself,” she says.

Rhoda, Irene and Gary’s daughter, is a veterinary assistant who tries to care for her parents and her dentist boyfriend, Jim, who explores the shallows of his narcissism while Rhoda pines for their imagined wedding. Rhoda’s brother, Mark, is on the social margins: He lives in the woods with his girlfriend, Karen, under circumstances much like the frontier experience his father craved years ago: He and Karen don’t care that there isn’t any running water; they’re content to fish and get high.

A stunning young tourist, Monique, arrives, bringing sexual manipulation and heat to the novel: She is a deus ex machina both hellish and sublime. The book is powerfully propulsive, in part because Vann organizes chapters and sections from each of these characters’ points of view — and these alternations temper the claustrophobic misery of Irene and Gary’s relationship and create a dizzying momentum as well.

Vann locates his characters in an utterly convincing Alaska, but the natural world provides no ease for human anguish — nor is nature anything except a mirror in which these characters see what they wish to see: “Irene didn’t know how it could change so completely in even a day. A different lake now.” As the cabin-building project inches forward, Gary and Irene read their misery, and their punishment, in the world that engulfs their project. “Gary leaned into blasts of wind and rain as he tried to nail the next layer of logs,” Vann writes. “Time. He hadn’t finished on time, and now he would pay the price. A thirty-degree drop in temperature, the sky gone dark, a malevolence, a beast physical and intent.”

Vann’s writing is confident — concrete and efficient. His characters’ emotions and experiences bleed directly into the reader; Irene, bone-chilled from an exhausting, wet day working on the cabin, finally gets into a hot bath, and the reader feels its heat: “She sank into it and closed her eyes, found herself crying carefully, without sound, her mouth underwater. Stupid, she told herself. You can’t have what no longer exists.”

Vann clearly has gifts for capturing emotional isolation and suffering. But it’s his ability to spin a riveting story from these dark materials that is distinctive. “Gary wanted to be desolate, alone, not even Irene to witness. He wanted her to disappear, vanish, never have been. Bitter woman, sulking in the tent, contriving punishments worse than any storm.”

Vann’s people are hurtling irretrievably toward a dark outcome, and while putting the book down might save you from it, you can’t stop reading, just as you can’t unlearn its truths.

Roper is an editor at Wired.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.