Remembering Carolyn Kozo Cole, whose ‘Shades of L.A.’ photo project revealed the city’s diversity

Carolyn Kozo Cole gave Los Angeles one of of its richest gifts — a deeper, broader and more complex visual record of itself.

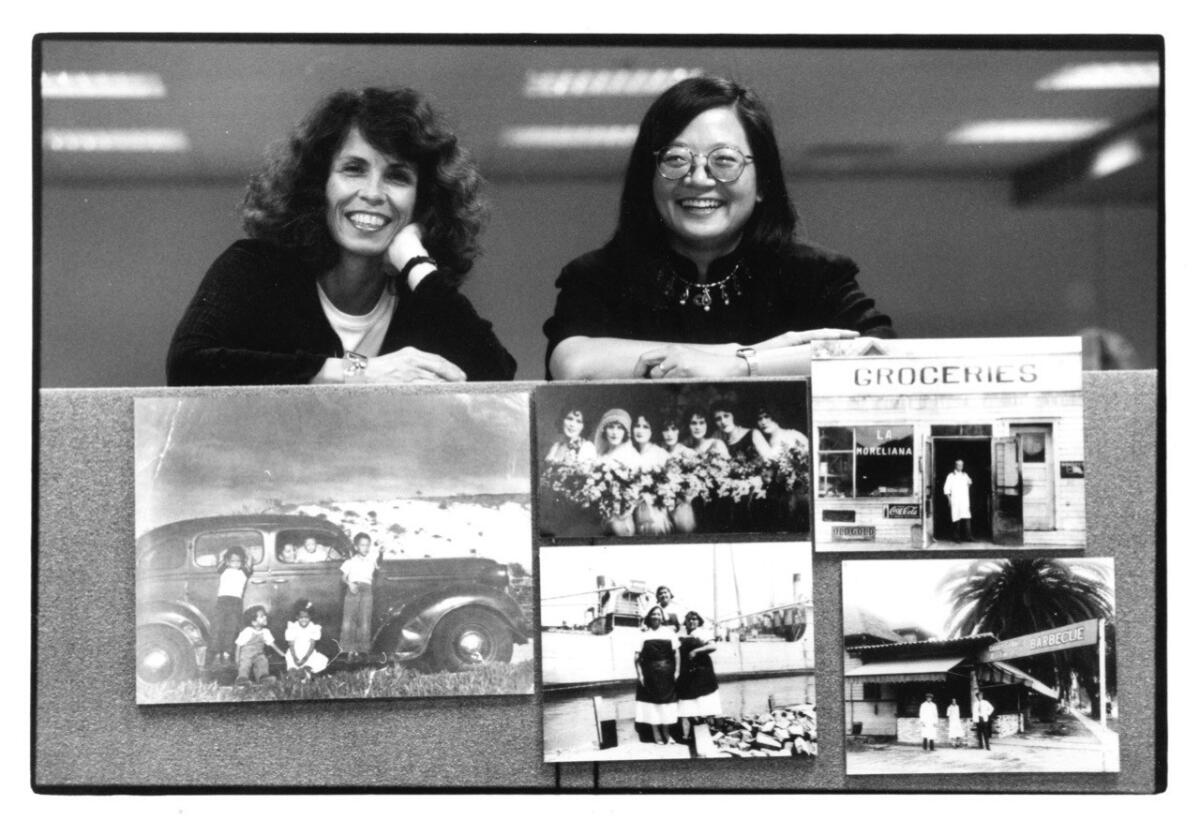

As head of Los Angeles Public Library photo collection for almost 20 years, Cole, who died Dec. 6 because of complications of Alzheimer’s disease, is best known for her landmark project, “Shades of L.A.” The initiative collected thousands of photos from across the region — including a Japanese American family in their Sunday best posed before Disneyland’s Sleeping Beauty Castle to African American couples relaxing at the Last Word club on Central Avenue — to create more reflective vision of our city in the world’s imagination.

Cole dreamed up “Shades of L.A.” after hunting through the central library’s 2.2-million-piece archive looking for quotidian photos of life in Watts — houses, business, nightlife — before the 1965 uprisings. She was struck by what she didn’t see. L.A.’s landmark buildings were present . She found images of some now-vanished neighborhoods, civic life, suits and ties, ribbon-cuttings; and Hollywood and society life. But what of day-to-day Los Angeles life? And more specifically: what about ethnic Los Angeles — Boyle Heights, Maravilla, Jefferson Park, Central Avenue?

Where was that rich L.A. tapestry?

I first met Cole in the early ’90s while on assignment for the now long-gone L.A. Style magazine. When I arrived at the small South L.A. library branch with my notebook and recorder, ready to do some reporting on the inaugural “Shades” photo gathering project, I didn’t know quite what to expect. Neither did the folks who were running things that day. Including Cole. It was all brand-new; an exciting experiment.

It occurred to me that the city’s missing history might be found in family albums.

— Carolyn Kozo Cole

The idea was that people would bring in their casual snapshots from their family collections and the photographers would copy them on the spot. Inside the library, a small photo crew was set up in a studio, with a camera mounted on a stand. Outside, we stood in the library’s parking lot and took in the details, chatting with an enthusiastic gathering of locals — early birds, loaded down with totes and frayed at-the-edges photo albums. Some carried shoe boxes and hat boxes, while others cradled bankers’ boxes. Some participants had just had pulled framed photos right off their mantels, walls or nightstands.

Cole was looking for the quieter moments that would explain the diverse lifestyles in the city: What did people plant in their gardens? What did a backyard birthday party look like? Who had cookouts in Griffith Park? What was it like to sunbathe on a segregated beach?

But where would one find photos like these?

Her brainstorming took her back to her childhood in Virginia: “I would spend long hours in my grandfather’s portrait studio, watching his assistant develop prints of family portraits and snapshots,” she would reflect years later in the introduction to the book “Shades of L.A.,” which showcased the project’s highlights. “It occurred to me that the city’s missing history might be found in family albums.”

The crush of waiting residents lining up as the day progressed said it all. Word of mouth brought even more. Her instincts were on the nose. The “Shades of L.A.” project would become a model for collecting programs across the state, and later the country.

People stood in snaking lines, but there didn’t seem to be a moment of impatience. Neighbors — current and former — chatted amiably as they waited. I watched and listened as communities from 30, 40, 50 years ago vividly reemerged, and old friends reconnected in the space of a small library reading room.

Carolyn was looking for the quieter moments that would explain the diverse lifestyles in the city.

I devoted a few more weekends following Cole and her caravan, watching her crew collect images and the serendipitous histories that went along with them. Her enthusiasm was as bottomless as it was contagious. These gatherings were festive; they had the spirit of reunions, each story about each photograph would fill in a gap not just in the library’s holdings but in our own collective memory.

These sessions were so transformative that once my story went to press, I volunteered to continue helping Cole — interviewing scores of Angelenos about the faces in and context of those frames.

Over time, the collection amassed about 10,000 images that explicitly and indelibly showcased Los Angeles’s diversity — both of people and place.

I remained in conversation with Cole for many years after “Shades.” She remembered my passions and passed along little packages of ephemera — books, business cards, old letterheads from a vanished Los Angeles. “This told me it belonged to you!” I would call her with questions or would hunt her down if someone had “gifted” me a lost family member’s photo archive. More often I would consult her if I knew of someone who needed to find the impossible. If anyone could, it was Carolyn. Novelists, playwrights, historians, set designers and musicians have spent hours in the collection looking to reanimate or understand Los Angeles.

I don’t know anyone who loved Los Angeles quite the way Cole did. Photographs — and photographers — alter our perspectives, allow us see the world in a fresh and unique way. And while I encountered Cole as a librarian, I learned soon after that she also was a photographer. She understood her archiving approach the same way a photographer might view subject matter through the lens — writing with light, reframing expectations, preserving the fleeting and capturing the unexpected.

Lynell George is an L.A.-based writer. She is the author of “After/Image: Los Angeles Outside the Frame.” She won a 2017 Grammy for her liner notes for “Otis Redding Live at the Whisky A Go Go: The Complete Recordings.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.