A murder, a memoir and the secrets that bind them together

The murder occurred in February 1992, in a shabby house in a small town in Louisiana. A 6-year-old boy named Jeremy Guillory was looking for his friend Joey. Beloved BB gun in his hand, he knocked on Joey’s door. The man who opened it was Ricky Langley, a 26-year-old man who lived with Joey’s family and often watched Joey and his sister, Joy. A pedophile who previously served time in Georgia for molesting a little girl, Langley welcomed Jeremy into the house, where he was alone; the boy’s body was found three days later wrapped in a blanket and propped up in a closet, the BB gun leaning against the wall next to him.

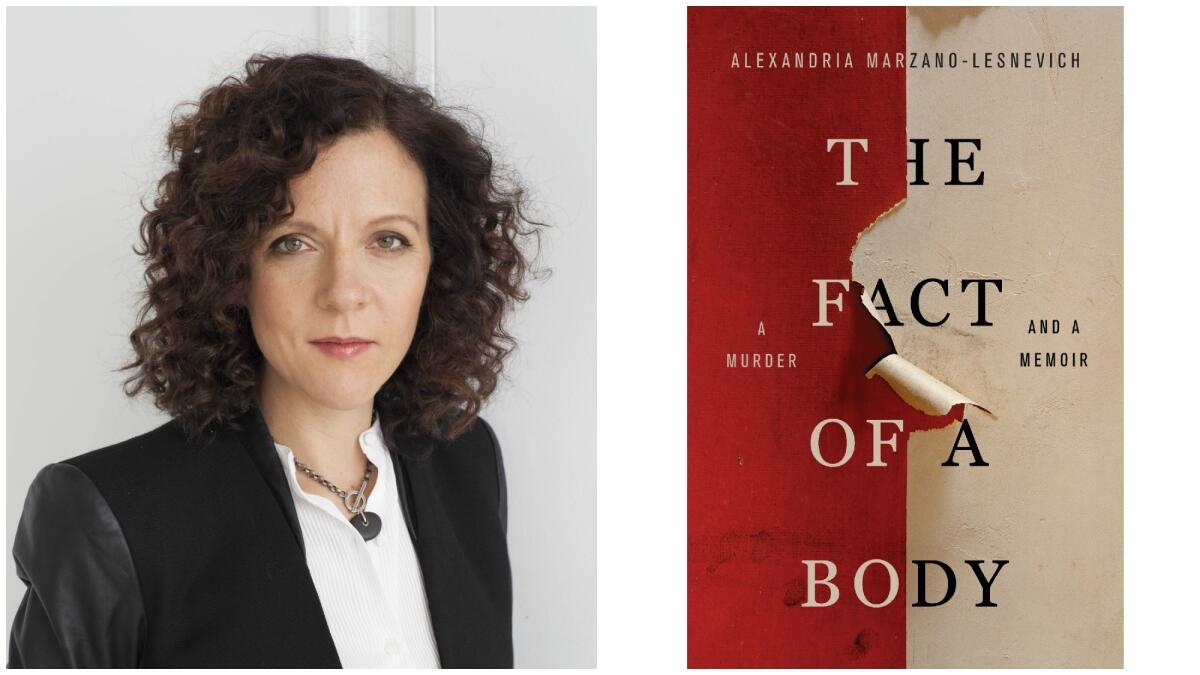

Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich first saw Langley on videotape in a Louisiana law office while working as a summer intern for the firm defending Langley in his death-penalty appeal. She had studied the law even before entering law school; as the child of two lawyers she had absorbed its ethos. The young law student was surprised by her reaction to the man on the tape. “I came here to help save the man on the screen,” she writes.

She felt her previously solid opposition to the death penalty shudder, then crack. “Despite what I’ve trained for, what I’ve come here to work for, despite what I believe,” she writes. “I want Ricky to die.”

In her intense, often harrowing “The Fact of a Body,” Marzano-Lesnevich braids together the story of the Guillory murder and its legal aftermath with her own story, which also includes her sexual abuse as a child by a relative, questions of guilt and punishment and the lingering effects of familial secrets and lies. For Marzano-Lesnevich, these included deeply buried facts about her own birth and infancy, as well as a kind of conspiracy of silence around her grandfather’s habit of entering her childhood bedroom at night. Once they are told, her parents’ response is to “model unaffecteness,” Marzano-Lesnevich writes. “They arrange the memory as carefully as a script.”

Of course, her trauma is no less damaging for its being kept quiet; as she enters adolescence Marzano-Lesnevich struggles with an eating disorder, sinks into a bed-bound depression, her days “webbed and sticky with the cotton of sleep.”

The mission at the heart of this book is Marzano-Lesnevich’s attempt to understand Langley, and her own abuser, by exploring more deeply who she herself is...

Langley, the killer, also bears the scars of family wounds. Born while his mother was in a full-body cast following a car accident that took two of his siblings, he grew up haunted by the shadow of his lost brother, Oscar, and marked by the affects of his mother’s prenatal drinking and drug use. He may or may not have been beaten by an abusive father (accounts differ). He was a strange child, small and friendless, and knew by the time he was a teenager that he had a problem with sexual attraction to little children. As Marzano-Lesnevich recounts, Langley tried to get help, wanted to be cured, but through a combination of institutional bureaucracy and the stubborn, intractable fact of his own pedophilia, never was. “The man at the center of this trial,” she writes, “will remain an enigma. … What you see in Ricky may depend more on who you are than on who he is.”

Stories take on different meanings depending not only on who tells them, but on how they are shaped — who decides when a story starts, when it ends, what the most important characters are? The mission at the heart of this book is Marzano-Lesnevich’s attempt to understand Langley, and her own abuser, by exploring more deeply who she herself is: as a sexual-abuse survivor, a daughter, a sister, a lawyer, a writer. As a law student, she studied the concept of proximate cause through a classic case involving an accident in a railroad station. “The idea of proximate cause is a solution,” she writes, and the problem it solves is one inherent in storytelling as well as law: how far back do we go to understand what happened, and whom to blame for it? How do we make of our lives — or any lives — a story that makes sense?

These questions have always been relevant but feel particularly urgent at the moment. True-crime storytelling has become one of the hottest genres in books and television; Marzano-Lesnevich’s work here shares similar concerns to those raised by the popular documentary series “The Keepers” and “Making a Murderer.” Perhaps inevitably, “The Fact of a Body” also raises some of the same questions about its own fidelity to truth. For a book so concerned with the vast and often unacknowledged power in how we choose to frame our stories, it’s a little disquieting how often Marzano-Lesnevich rearranges reality to suit her own narrative needs. She acknowledges in an author’s note and a separate essay on sources that some scenes are compressed, dialogue invented and details imagined.

This is not to indict book or author. As Marzano-Lesnevich writes, “[n]o one story is simple. No one story complete.” Someone is always selecting the point at which to begin a narrative, the proximate cause to assign credit or blame for every victory or tragedy. Art that both entertains and challenges us to look at very unpleasant truths — even when it poses disorienting questions about the nature of truth itself — is always more vital than art that seeks to comfort, to silence, to bury. So if “The Fact of a Body” ends up making readers question just what a fact is, maybe that’s about as useful as a book can be in today’s world.

Tuttle is the president of the National Book Critics Circle.

“The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir”

Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich

Flatiron Books: 336 pp, $26.99

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.