Michael Ondaatje’s novel ‘Warlight’ is a masterpiece of shifting memory

It happens in the time it takes to read a phrase: an epileptic seizure described as “some deadly shore recently passed.” You understand that the work you’re reading is both more complicated and more beautiful than the otherwise plain prose might indicate.

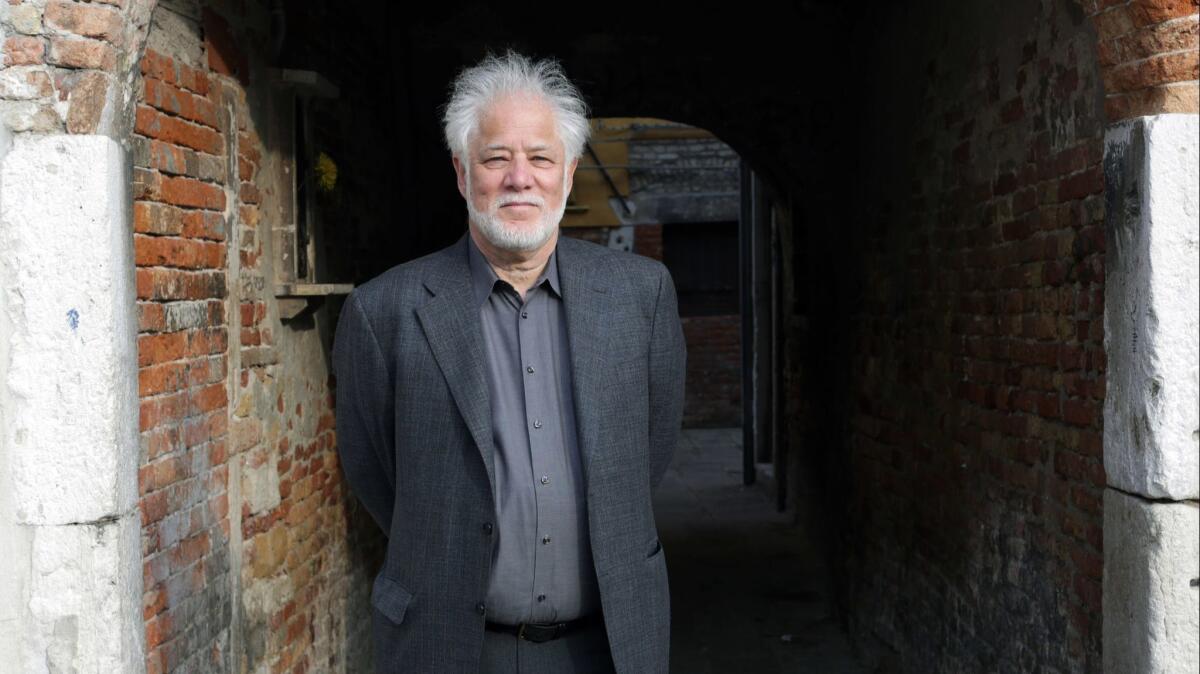

Of course, you already knew that, because you’re reading a book by Michael Ondaatje. Many readers recognize his name primarily because of his bestselling novel “The English Patient,” which was made into the 1996 blockbuster movie that received nine Academy Awards. But while that book shares with this new one a World War II setting, “Warlight” owes more to Ondaatje’s career as a poet than it does to that famous novel.

The title alone casts the entire story in an eerie glow; “Warlight” was the official name given to lights allowed on for emergency traffic during blackout hours in Blitz-ridden London.

“Warlight” begins as Nathaniel’s story. He is 14 and living with his parents and 16-year-old sister Rachel. It is 1945, the war has just ended, and the parents announce they are heading to Singapore, where the father will take a new position as head of marketing for Unilever Asia. The mother carefully packs her trunk: “We watched as she filled it with frocks, shoes, necklaces, English fiction, maps, along with objects and equipment she did not expect to find in the East.” The siblings are distressed at being left to enter British boarding schools, but more distressed at being left in the care of a very odd family friend, a man they privately refer to as “The Moth.”

The adventures that follow for Nathaniel are triggered both by hormones and by finding, with his sister, their mother’s full, unsent trunk in the basement. The game’s afoot, but no one will tell them any of its truths. One night, dancing at a club, Nathaniel thinks he glimpses his mother, Rose. She’s supposed to still be in Singapore. Has she returned? Why would she stay on the periphery of her children’s lives?

Not until years later, when Nathaniel has taken an archivist position with British Intelligence — it comes open for him with strange convenience — will he learn some of the answers. Each layer of this unusual family’s history arrives via flickers of memory, and not all the layers are primly opaque: Rachel begins experiencing epilepsy’s grand mal seizures. Barges transport illegal greyhounds to dog tracks. Rose has arms crisscrossed by terrible scars.

Despite the spotty parenting, Nathaniel comes to realize how strongly he and Rachel have been cared for. Some of the strange arrangements Ondaatje dreams up and pieces together make it seem as if the whole of Britain were involved in spy craft, that every farmer and member of “Dad’s Army” was fighting for the cause. Especially strong are Nathaniel’s work for and interactions with one Mr. Malakite, strong as a workhorse but also able to keep a secret as well as any of his colleagues.

Props to the Knopf design department for its evocation of the glow on the book jacket, which includes black-and-white photography along with various shades of blush, indicating how sodium lamps might have appeared through fog — and how the novel’s mysterious layers appear and disappear in Nathaniel’s memory.

The story’s second half takes a sharp turn, starting with an anecdote about a young boy in a thatching family who fell off a roof and had to be cared for by 8-year-old Rose. That boy is Marsh Felon, who grows into a “gatherer,” a man who recruits people for intelligence services during wartime and long after.

It’s important for Nathaniel to re-create scenes of his mother’s interactions with Felon and other operatives, both to understand her devotion to her trade and to understand the life she lived apart from her children. The result is quite a look at what it was like to be a loyal foot soldier in a war while being a working mother, decades before women were officially allowed as military combatants in most Western countries.

Ondaatje has further to go with his artistic purpose, however. As Nathaniel grapples with the documents and information available to him at work, he also grapples with the characters from his past, including the man who smuggled greyhounds, a man Nathaniel and his sister called “The Darter.”

Giving too much information about their relationship might be considered a spoiler, but their postwar nighttime river jaunts turn out to have had a more serious purpose than Nathaniel could have known.

Which is, at the heart of it, what connects the natural world to the human one of war and intrigue for Ondaatje. A girlfriend of “The Darter,” Olive Lawrence, is an ethnographer (at least in part), and at one point, she takes Nathaniel and Rachel on nighttime walks in London. As she points out sights and sounds, including cricket hums and the rasping of badger paws, she reminds Nathaniel, “Your own story is just the one, and perhaps not the important one. The self is not the principal thing.” The poetic use of natural imagery in “Warlight” will keep readers ruminating on how easily the world around us adapts to human foibles.

And yet, the world is also messy. Nathaniel seeks to create a narrative of the war years, but his life and his stories have plenty of holes. Do we need to obtain answers, this novel asks, or might we learn to relish ambiguity? In a book made lush through layers of experience instead of description, the latter feels possible.

Patrick is a writer and critic whose work appears in the Washington Post and on NPR Books.

“Warlight”

Michael Ondaatje

Knopf: 304 pp., $26.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.