Carolyn See’s California, as told to Barbara Isenberg

The celebrated writer and teacher Carolyn See, who died in Santa Monica last week at 82, was born in Los Angeles and never really left home. She described raw silk as the flannel of the desert, and wrote evocatively of her home state in nearly all her books. For her, California was the repository of America’s dreams, a place that is to America what America is to the rest of the world.

Few people tell stories quite the way Carolyn did — leaning across a table and luring you into her confidence, sharing some terrific observation, then punctuating it with a knowing laugh. What was always amazing to me was that she could create that same intimacy on paper. You were hooked whether you were sitting across from her in a restaurant or reading her latest novel by yourself at home.

Her California, the place she lived and wrote, was the subject of an interview I did with her in May 1999, and as the following excerpt shows, few knew the Golden State better than Carolyn See.

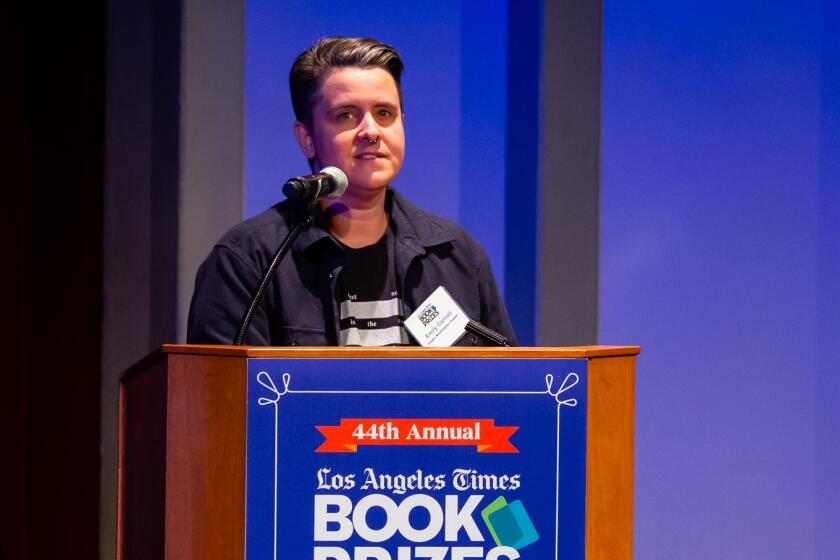

Carolyn See reads an excerpt of her novel “Golden Days” for the L.A. Times Book Prizes in 2008.

See said:

When I talk to my students about writing, I talk about character and plot, space and time, but, most important, geography. Place has always been where you start. The more specific you can get about a particular place, the better chance you have of making it be universal and of really grounding it.

Geography dictates what you write. Any novel depends primarily on setting, more even than on the characters.

It seems to me that’s why California literature is pretty much an entity unto itself. The potential here is still untapped and hasn’t been written, so it doesn’t have to be the same old tiresome tragedy. There is a whole quality of hope here that the future is still open-ended. In the way that people used to come to America -- this is a platitude, but what the hell -- to shed their past and fulfill their dreams, now they come from the East to California.

Clara, my younger daughter, has worked with the homeless in Santa Monica. I was talking to a lady on one of the boards there, and she said, “Our homeless are a cut above because they have the sense to take the bus from downtown where it’s so awful to the beach where the climate is better.” That whole westward movement is, of course, inherent in all of American literature, but also I think in every one of my books there’s been a movement from the center of the city to the beach. When you get to the beach, that’s the end and you feel better.

My novel “Golden Days,” which ends on the beach, is set in Topanga Canyon, where people survive nuclear war because of those sheltering walls of earth. And also because they’re so damn crabby and ornery.

When you wake up in Topanga -- assuming it’s one of those beautiful days -- the birds are going crazy, the coyotes have been yapping all night, the trees are just breathing and the aromas are intense. The acacia is bright, bright yellow. So then you hang out, the same as you would any other place, except you’re hanging out in the most beautiful place in the world.

But when the fires are coming, or when it’s just high summer, it is agony. You wake up in a pool of sweat. You take four showers a day. There are tarantulas in the garage, and rats and snakes, and everybody’s in a bad mood because it’s so hot, including the rats and snakes and tarantulas. We had air conditioning but it didn’t work; it was hotter than the air conditioning could handle.

There was a bitch of a fire in 1995. We’d been through a lot of fires, one after another, in our 32 years in Topanga. But this thing was traveling so fast, and it started so close to us. It was one of those horrible hot days, and I heard a helicopter which of course is the worst news you can have.

Since there’d been fires all over town, we already had the car packed up. We’d certainly gotten out of the house many times. I’d say 15 times in 30 years. That’s what you do when you live up there. You have everything packed up and then you stay until the last minute.

It’s sort of standard procedure if you live in Topanga to always have a list of stuff to take either by your front door or on the refrigerator. My list was always on the refrigerator door: the family Bible, the family photographs, passports, insurance, the portraits by Don Bachardy, and Sleepy and Squarey, the two toys Clara slept with when she was little. Even after she’d moved out of the house, she’d say, “If there’s a fire, be sure and pack Sleepy and Squarey.” When Lisa was home, we had other stuff.

You’re terrified, but you also love it because there’s no other time like it. The air is so dry that you’re almost dehydrating. You can’t catch your breath. You’re gasping. Your mouth and eyes are dry. Your breath rattles in your throat. Your adrenaline is so high you’re trembling. There are times when the fire goes through and you watch it, and it makes a sound like a train bearing down on you. It sucks the oxygen out of the air.

When the floods come, people get very depressed. A flood is a whole different thing. It’s cold and damp and nasty. You’re wet, and it takes forever to get finished. But the fires go by so fast. They crackle. They’re so spectacularly beautiful, so awe- inspiringly dangerous, that you go through a fire on an adrenaline rush. All this stuff is very biblical, you know, which again leads you to write a little bit beyond the constraints of ordinary life.

Even in Los Angeles you’re just three or four days away from dying of thirst and exposure if anything happened to the water supply, because we’re in the desert. This is one of the few cosmopolitan cities that goes so against nature. That’s why people in the East are always foretelling our doom, and they may be right, although it hasn’t happened yet.

There’s that giddiness that also may have to do with Hollywood and the hope that you might strike it rich. It’s a sense that although there are sociological classes, they’re still amorphous enough that you can crash through one class to another. You can still be upwardly mobile here.

Most of our futures are probably grim, and probably, for most of us, this is still a vale of tears. But in California there is the gold rush, okay? Simon Rodia had a vision that had to do with air and trash and he turned that into the Watts Towers. There are lame-brain starlets who make it in the movies. There are businessmen who look out on nothing, see tract houses and turn from dumb contractors into multimillionaires. And there are baggy old crones who go to good plastic surgeons and turn back into 30-year-olds.

These are things that you can’t get away with in other parts of the country, I don’t believe. People would say, “You’re 65, for God’s sake, Mother! How could you humiliate us by changing your appearance?”

Midwestern books are mostly about endurance and hard times, and novels set in New York, Connecticut and those places are about class and pressure on the individual. Frankly I’m glad that I live out here because I love writing about futures that aren’t set in stone, and pasts that you can invent and reinvent.

In my books people pretty much end up on a voyage or on the beach, going somewhere in a state of hope or in a state of happiness. And that’s true even in “Golden Days” where I used some of the worst images of nuclear war that I could find. The sand on the beach melts into glass, and I thought, well okay, what do you do with it then? You windsurf on it. So when the characters come down out of the canyon, the beach is glass, it’s the colors of a juke box, and a few hearty souls are wind-surfing.

At a cocktail party in New York some years ago, a gentleman said to me, “Ah, yes, you’re from California. I always feel that New York is the brains of America, and California is the genitalia.” He gave me this big dumb smile, and I thought, Given that choice, which he presented so clearly, where would you rather be?

See’s remarks are excerpted from Barbara Isenberg’s book, “State of the Arts: California Artists Talk About Their Work,” published by William Morrow in 2000.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.