Ban lifted for green-card applicants with HIV

A stamp in Heidemarie Kremer’s passport reveals her health status as HIV-positive.

Because of the disease, Kremer -- a native of Germany -- has been barred from becoming a legal resident of the United States. She and her two children are fighting possible deportation, and their plans for the future are on hold.

But that soon may change.

This month, the federal government cleared the way for HIV-positive foreigners to visit the country and apply for green cards, lifting a bar that has been in place for more than two decades.

Kremer, 46, a trained physician and HIV researcher who lives in Miami, said she was relieved that her case might be resolved when she returned to court in February. But she said she also felt a sense of responsibility.

“This is not the end of the story,” she said. “What about all the lives that the HIV travel and immigration ban ruined?”

Immigration lawyers in California and around the nation said the ban had caused families to be separated; foreigners to avoid being tested or to go without medication; and highly skilled workers to return to their home countries.

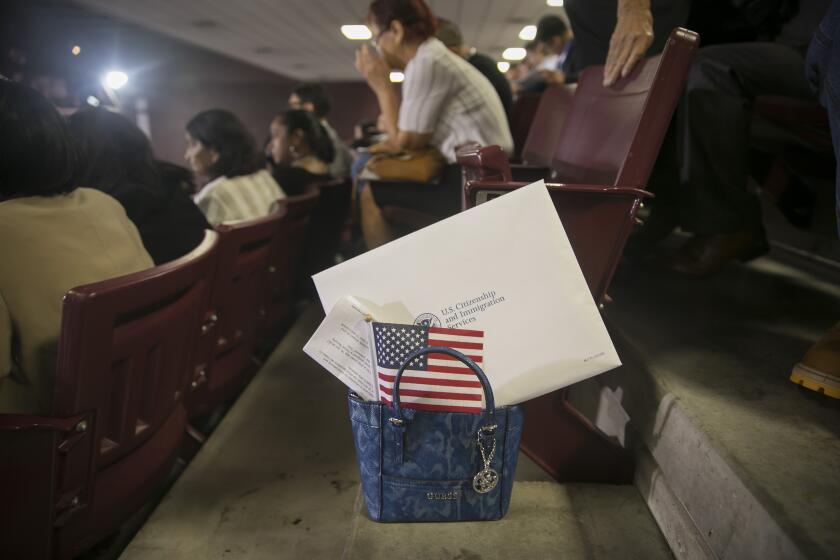

Since the announcement, Los Angeles immigration lawyer J Craig Fong and other lawyers said they had received a flurry of calls and e-mails from HIV-positive foreigners who now had renewed hope. The new rules, including the elimination of HIV testing for green-card applicants, take effect Jan. 4.

“To finally be in a position where I can tell people that they can come to the United States to visit their family or that they can get a green card and stay here with their partner is just incredible,” said Victoria Neilson, legal director for Immigration Equality, a national organization that advocated for lifting the ban.

But Mark Krikorian, executive director for the Center for Immigration Studies, said the decision to remove HIV as a bar was based on politics, not science. “It was clearly a politically motivated move,” Krikorian said, adding that the decision could have real consequences -- more HIV cases and more costs. “It is extra healthcare spending that we wouldn’t have otherwise.”

An analysis by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that in the first year, an estimated 4,275 people infected with HIV could come into the U.S. at a cost of about $25,000 each.

The ban on infected foreigners began in 1987, when federal health officials added HIV to the list of communicable diseases that prevented people from entering the country. In 1993, Congress made it law.

“At the time, much less was known about HIV,” Neilson said. “People were really scared that HIV status was a death sentence.”

People could apply for waivers, but for most applicants that required proof that the foreigner had a family member in the U.S. legally. Because same-sex partners don’t qualify as family members under the law, the requirement was difficult for many to meet.

Last year, Congress changed the law, and this month, the CDC removed HIV from the list of diseases restricting foreigners’ entry.

Kremer was infected as a medical student in Germany. In 2001, she received a visa to come to the U.S. on an educational exchange program and later qualified for a visa for highly skilled workers. Her original waiver -- granted by a sympathetic consular officer in Berlin -- was automatically renewed.

But when Kremer applied last year for a green card, she was denied based on her HIV status, and she and her family were placed in removal proceedings. “I was fuming,” she said. “My whole future was built up to stay in the United States.”

Knowing the change in policy was coming, her lawyers pushed to get her case postponed until after the new year. Kremer, whose treatment is paid for by the German government, said she was thankful to have both medical coverage and immigration lawyers.

“I am concerned about other people who have been affected who aren’t fortunate enough to have attorneys who know how to navigate the system and keep people from being deported,” she said.

Another HIV-positive visa holder, who lives in Southern California, has also had access to an immigration lawyer but hasn’t been able to apply for legal residency.

Dave, who did not want his full name or occupation used because his HIV status is unknown to his employer, arrived from Canada a decade ago as a visitor. He soon found a job and was able to get an H1B visa for high-skilled workers. Now, he earns six figures and manages million-dollar projects.

Dave’s employer offered to sponsor him for a green card, but Dave couldn’t move forward because he knew how it would end -- with a denial. His visa expires next year, and he had started looking for new job opportunities.

“Everything had a finite end to it,” he said. “You were working within certain boundaries. Now those boundaries have been removed.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.