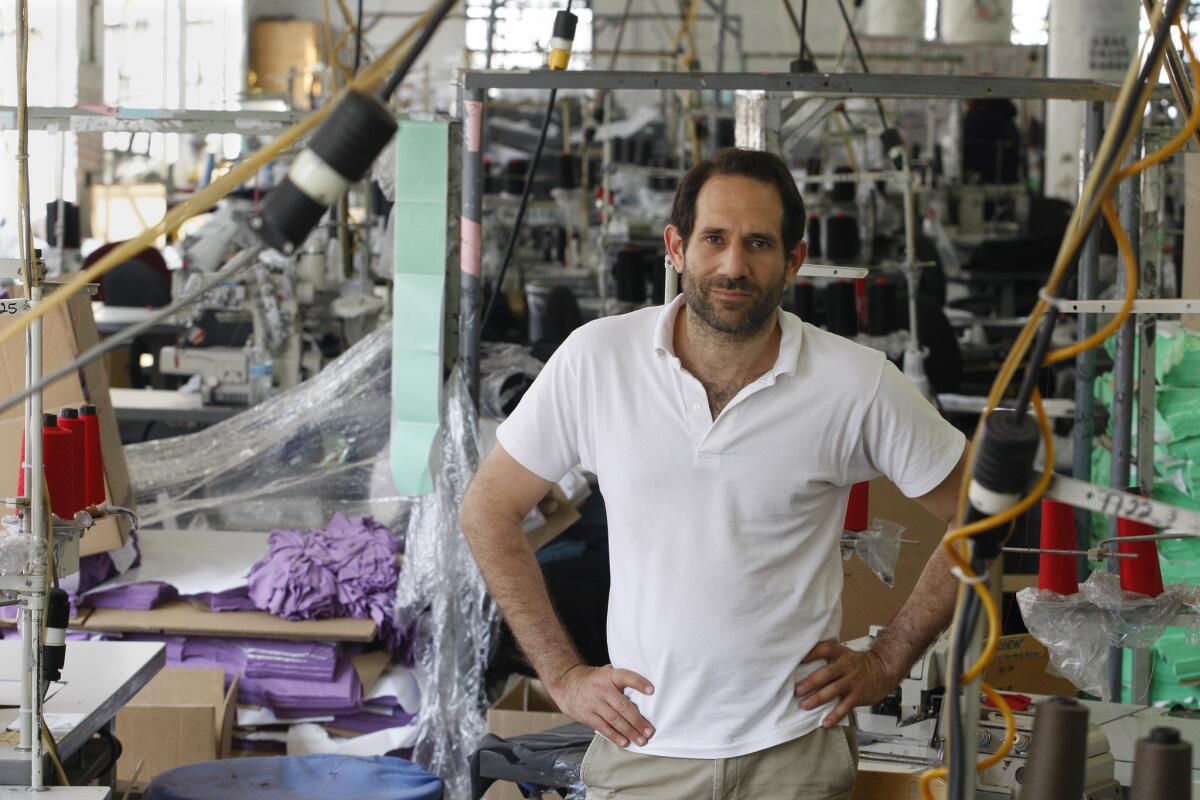

Column: Is the final chapter in Dov Charney’s steamy American Apparel tale being written? [UPDATED]

Courtroom testimony has just ended and a Delaware bankruptcy judge will have the last word, but it’s beginning to look as if the curtain soon will fall on the saga of Dov Charney and his brash clothing retailer, American Apparel.

Bankruptcy Judge Brendan L. Shannon is expected to rule Monday on the Los Angeles company’s plan to emerge from bankruptcy with new financing and with no trace of Charney, the firm’s founder, in management or even behind the scenes. The plan has the approval of creditors and the hedge funds that would be in the driver’s seat.

[Update: Bankruptcy Judge Brendan L. Shannon confirmed American Apparel’s bankruptcy plan Monday, ending founder Dov Charney’s attempt to retake his company with hedge fund backing.]

The one certainty about such an outcome is that without Charney, 46, the retail world will become a lot more boring. Among the uncertainties is whether Charney will go quietly, since he’s still promoting a plan to retake the company, backed by a $300-million hedge fund loan. The American Apparel board rejected the plan, but Charney maintains its hostility is blinding his proposal’s real economic value.

Among the questions yet to be resolved is whether it’s too late for the money-hemorrhaging American Apparel to turn itself around. The board fired Charney as chairman and chief executive in 2014 for a raft of alleged misdeeds, personal and financial. As we observed at the time, the question wasn’t so much why Charney was sacked, but why it had taken so long. The retailer hadn’t notched a profitable year since 2009 and had faced numerous lawsuits targeting Charney for sexual harassment.

One reason for his longevity was that he had shown he could be successful. Starting out in 1989 by “smuggling Hanes T-shirts” across the border from his native Canada, as his official corporate biography put it, he had developed American Apparel into the “largest domestic clothing manufacturer” in North America, with 246 retail stores in 20 countries.

Charney combined theatrically bad-boy manners with a stated commitment to labor, especially immigrant labor, and to the “Made-in-America” movement. Both aspects of his character contributed to the company’s edgy cachet. He once masturbated in front of a reporter for Jane magazine, advising her that “masturbation in front of women is underrated.” American Apparel’s ads and billboards were exceedingly sexualized.

On the other side of the coin, his labor policies were frankly progressive. In 2006, we reported that he was paying an average $12 an hour, about twice the then-minimum wage. He offered company-subsidized health insurance for $8 a week to employees working 32 hours a week.

American Apparel’s most profitable year as a public company was 2007, when it recorded $15.5-million net income on $387 million in sales. Its subsequent slide is the result partially of the recession, partially of Charney’s management. His successor as CEO, Paula Schneider, says she found the place an undisciplined shambles when she arrived in January 2015.

That said, Charney is right to assert, as he did in a court filing last month, that financial results have deteriorated at American since his ouster. The company’s peak sales came in 2013. In the first half of 2015 they fell more than 13% from the same period a year earlier and the loss more than doubled to $45.8 million. In November, the most recent month reported, sales slid to $22.3 million from $29.2 million in October as the holiday buying season heated up. The monthly loss more than doubled from October’s to $14.5 million. Last year was “the worst performing year in the company’s history on almost every level,” Charney stated.

Manufacturing calendars were out of whack with selling seasons, with no process in place “for determining what items would be manufactured, when they should be in the stores, and what ... to do with items that do not sell,” Schneider said in a declaration to the Bankruptcy Court. About 70 people reported directly to Charney. In the five years before her arrival, the company had amassed $250 million in debt, carrying interest rates as high as 17%, and $338 million in losses. The company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in October.

The board and some investors seemed to have twiddled their thumbs while the wreckage piled up, possibly hoping that Charney would eventually bring back the magic. Standard General, a New York investment fund specializing in distressed firms, says it bought into Charney’s “fundamentally compelling vision — a socially conscious mission to manufacture clothing in the USA.” It started backing Charney in June 2014, a week after the American Apparel board suspended him pending a further investigation.

In a lawsuit it filed against Charney after the dime dropped that its would-be partner wasn’t as tamable as it had thought, Standard implies it accepted Charney’s denial of wrongdoing and his repeated assurances “that a neutral investigation — which he claimed he had been denied — would vindicate him.”

The firm says it recognized “that the question was one for the board of the public company not for a prospective investor.”

Its claim that a wait-and-see approach was warranted carries little more weight than the American Apparel board’s explanation that it delayed sacking him because until mid-2014, the charges against him appeared all to be based on “rumors and stories in newspapers.”

Rumors? Stories? The company’s 2013 annual report stated that in August 2010, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission found in a case involving employee Sylvia Hsu that “reasonable cause exists to believe we discriminated against Ms. Hsu and women, as a class, on the basis of their female gender, by subjecting them to sexual harassment.” The company settled the case with a payment to Hsu of undisclosed size.

In 2005, the company tried to make a wrongful termination case filed by former employee Mary Nelson go away by entering an astonishing legal arrangement. Nelson had alleged a hostile work environment. The company agreed to pay her $1.3 million after a sham arbitration in which the arbitrator would issue a pre-cooked “decision” finding Charney blameless. This would enable Charney and American Apparel to issue a press release stating that “an arbitrator has ruled in their favor” and quoting Charney calling the fake ruling a victory for “the role of the First Amendment in the American workplace.” No mention of the payoff would be made. But no real arbitration would take place, either.

The deal collapsed when one of Nelson’s lawyers refused to attend the sham arbitration hearing. Subsequently, a California appeals court suggested that the whole arrangement harbored elements of “illegality, injustice and fraud.” The appellate judges didn’t speak to the spectacle of a public company plotting to lie to the public about a legal proceeding.

In 2011, a number of female employees sued Charney and the company for sexual harassment. As my colleague Andrea Chang reported, Charney’s response was to show reporters photos of some of the plaintiffs “posing nude in suggestive positions, in one case with Charney.”

In his last-ditch appearance last week before Judge Shannon in defense of his reorganization plan, Charney played the familiar role of the mistreated visionary. “I was doing something that was creative,” he said. “If it was unorthodox, it was meant to be. I’m a merchant, I’m a creative artist, I’m a photographer, I’m a marketer, I’m an industrialist.” The bankruptcy filing and the board’s machinations to keep him out were a plot and “coercion,” he said in a nonstop spiel the judge labeled “free associating.”

Whether he is sent off or comes back, Charney left a mark on retailing for the nearly two decades during which he ruled American Apparel. He was a talented and visionary entrepreneur devoted to his company, and more often than not tried to do the right thing by his employees. It was an imperfect effort, sometimes spectacularly so. Few executives in recent memory combine so many appealing and unappealing qualities in one body. Had Charney surrounded himself with people who could steer him from his basest impulses, his legacy might be secure. But it hangs by a thread, and that’s his tragedy.

Michael Hiltzik’s column appears every Sunday. His new book is “Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and the Invention That Launched the Military-Industrial Complex.” Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.