IMF agrees: Decline of union power has increased income inequality

Discussions of the causes of income inequality typically focus on financial deregulation and tax cuts for the wealthy as key drivers of the trend. In a new paper, the International Monetary Fund broadens the debate by taking a closer look at the effect of declining union power.

The IMF’s analysis undermines the accepted wisdom that lower union membership affects chiefly low- and moderate-income workers. The fund’s analysts, Florence Jaumotte and Carolina Osorio Buitron, find instead that the impact of declining unionization is felt across the entire income spectrum. The trend not only reduces the welfare of the lower income worker, they find; it makes the rich richer: “The decline in unionization,” they write, “appears to be a key contributor to the rise of top income shares.”

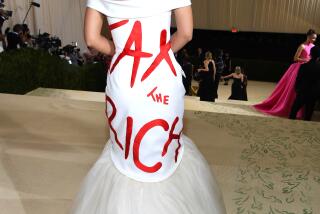

This is important because assaults on union power and members in the U.S. are on the rise. Most recently, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker signed a “right-to-work”--that is, union-busting--law, an action he’s sure to place at the top of his resume when applying to be the GOP nominee for president. The National Labor Relations Board comes under almost constant attack from employers and conservatives in Congress for rulings expanding labor organizing rights.

The backdrop is a nearly steady decline of labor’s share of the U.S. economy since the 1960s, coinciding with a similar drop in union membership in the private sector. (See related graphs.) The IMF analysis suggests these trend lines aren’t merely correlations, but the first is caused, at least partially, by the second. Indeed, the paper says that roughly half the increase in income inequality in advanced economies is “driven by deunionization.”

To the extent that income inequality allows the wealthy to “manipulate the economic and political system,” the analysts say there are grounds for government to take action--and if there’s any doubt that’s happening, just look at the torrent of money from corporations and the wealthy flowing into political campaigns, abetted by a string of Supreme Court decisions.

Among other remedial steps, the IMF points to “corporate governance reforms that give all stakeholders—workers, managers, and shareholders—a say in executive pay decisions; ... and reaffirmation of labor standards that allow willing workers to bargain collectively.”

An important part of the IMF paper is its analysis of how deunionization promotes inequality.

By weakening earnings for middle- and low-income workers by reducing their bargaining power, deunionization “necessarily increases the income share of corporate managers’ pay and shareholder returns....Moreover, weaker unions can reduce workers’ influence on corporate decisions that benefit top earners, such as the size and structure of top executive compensation.”

Unionization and minimum wages, the analysts say, reduce inequality by helping to equalize wage distribution across a corporation, not just at the bottom end of the scale. They dismiss the counterclaim that higher unionization is associated with higher unemployment. “The empirical support for this hypothesis is not very strong,” they say. An OECD survey of 17 studies found only three reporting a linkage.

Americans have become inured to the decline of unions, especially in the private sector, in part because they don’t appreciate the role of organized labor in much of the quality of modern life we all take for granted today--safety and child labor regulations, higher wages overall, retirement and healthcare benefits.

As I wrote last year, “the decline of all these features of the American workplace has coincided exactly with the decline of unions. That should tell you something.” The International Monetary Fund, an unexpected source indeed, has now stepped in with a sober analysis of what is being lost.

Keep up to date with the Economy Hub. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email mhiltzik@latimes.com.