China’s moon landing is part of a new space race by emerging nations

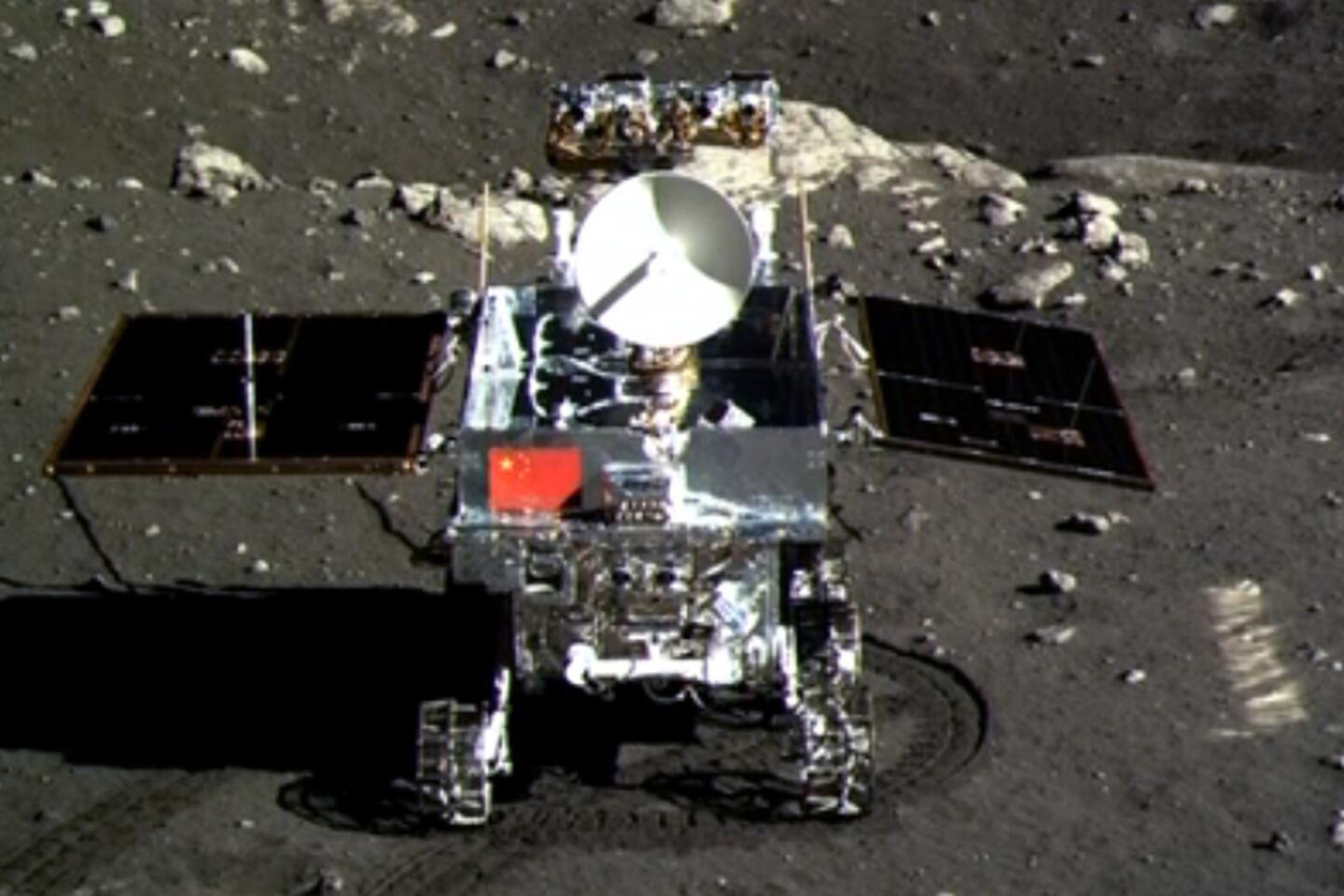

China watched this month as the nation’s first lunar rover rolled across the moon’s surface.

It was a moment of national pride when images of the six-wheel rover, dubbed Jade Rabbit, were transmitted live back to Earth, showing the red and gold Chinese flag on the moon for the first time.

“Now as Jade Rabbit has made its touchdown on the moon surface,” the state-run Xinhua news agency said, “the whole world again marvels at China’s remarkable space capabilities.”

The lunar triumph offered many Americans their first glimpse at an unfolding new space race involving countries with emerging economies. Space exploration, once the exclusive domain of the world’s superpowers, is now being undertaken by dozens of nations aiming to show the world their technological prowess.

Although these countries are still decades behind the United States in space technology, their push into the cosmos comes at a time when NASA has been wrestling with budgetary restraints and struggling to achieve new milestones in space flight.

It prompted Buzz Aldrin, the former astronaut now from Los Angeles and the second man to walk on the moon, to say in an interview that U.S. government officials lack leadership in space exploration.

“They are ignoring the achievements of what we risked our lives for,” he said. NASA’s funding “is totally inadequate for an endeavor that brings so much inspiration to the American people and educating the next generation.”

The U.S. must stay at the forefront of space exploration by helping all countries, including China, advance their programs, he said. An existing law prohibits NASA from working with China, but Rep. Frank R. Wolf (R-Va.), the fiercest opponent of international cooperation with the country, announced his retirement this month.

“A number of nations have evolved their capabilities to put humans into space and beyond Earth,” Aldrin said. “We should help contribute to their exploration.”

According to the aerospace consulting firm Futron Corp., China has had 15 launches this year with one more planned. Russia has had 32 launches, and three more are slated before the end of the year. The U.S. will finish with 19.

But space exploration has reached far beyond these three countries. About 70 nations have space programs.

Last week, the European Space Agency launched its $1.3-billion Gaia spacecraft, which is designed to map out more than 1 billion stars in the Milky Way. Iran has sent two monkeys into space — most recently last week — and has plans for a manned mission.

In November, India launched its first robotic probe to Mars. The country has already sent a probe to the moon and plans to send a second one by 2017.

None of these missions approaches the difficulty of the highly choreographed landing on Mars that NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada-Flintridge executed last year with its 1-ton Curiosity rover. But there are questions in the aerospace industry about what NASA’s next major milestones will be and how they will be funded.

The nationwide fascination and allure of the Apollo era is long gone. NASA accounted for more than 4% of the federal budget during the 1960s; now it is less than one-half of 1%.

NASA’s proposed budget is expected to be about $18 billion next year, and some in Congress want to slash it further.

To many Americans, routine flights of the space shuttle-era have made the feat rather mundane. There were major accomplishments and fatal accidents during the 30-year program, but it never captured the public’s imagination like the Apollo program. As a result, Congress feels little pressure to fund ambitious space travel at a time when the U.S. economy is sputtering.

In a study published this year, the Congressional Budget Office proposed cutting human spaceflight altogether. According to estimates, the move would save NASA $73 billion from 2015 to 2023.

Currently NASA has no way to get its astronauts to the International Space Station, other than paying $71 million to Russia for a ride.

NASA ultimately wants private companies to take astronauts to the station, but that hardware isn’t yet ready. The space agency also has plans to build a new launch system to send humans on deep space missions, including a mission to land on an asteroid by the mid-2020s.

But that plan has failed to gain widespread support, reflecting serious concerns about billions of federal dollars needed to accomplish such a feat and the lack of detail about the most difficult aspects of the mission. The total cost of the program and which asteroid NASA would visit remain unknown.

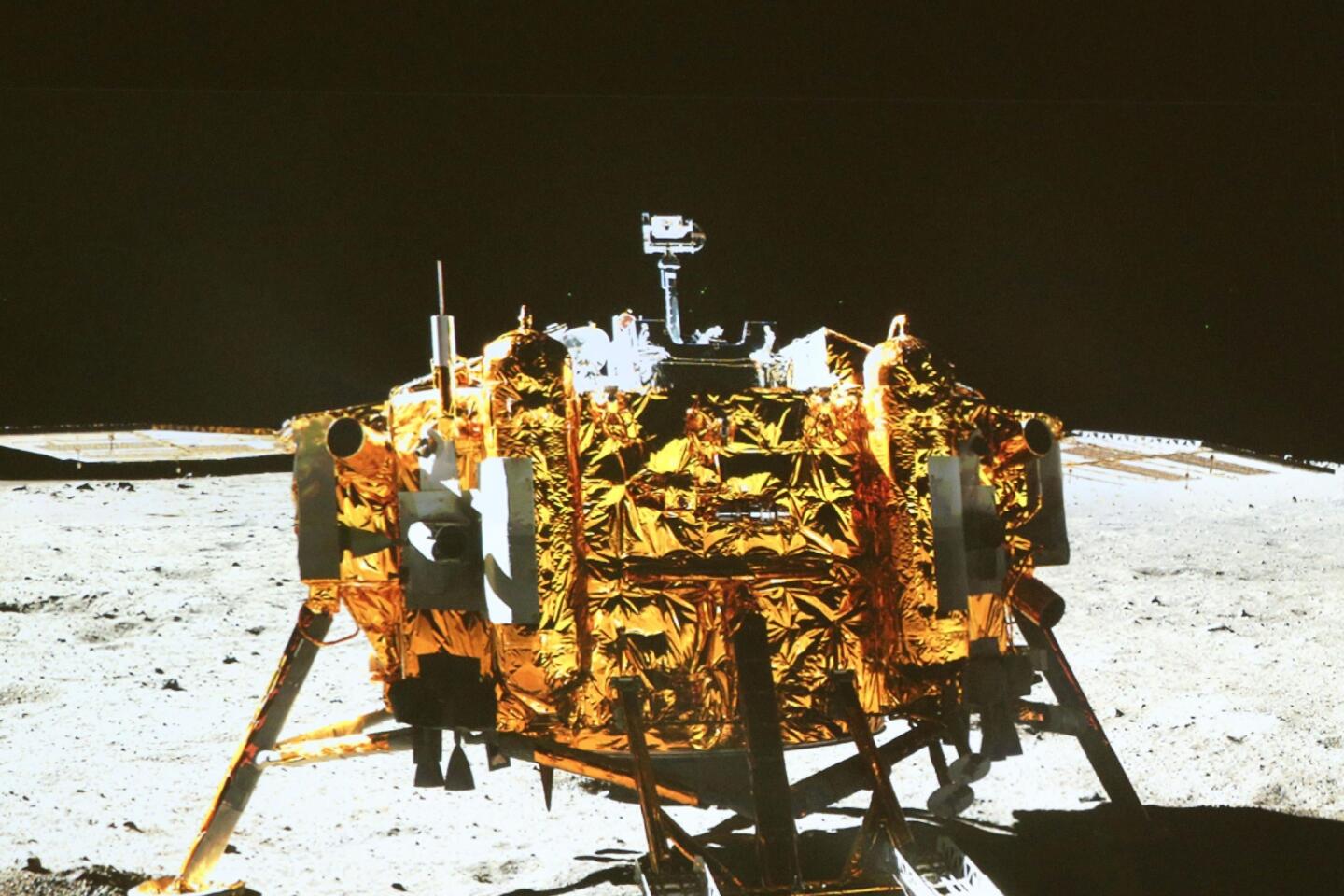

In a statement, NASA said it welcomes “all countries’ peaceful exploration of space, and looks forward to China’s public release of the scientific results from the Chang’e 3 mission to the moon.”

Gregory Kulacki, a member of the Union of Concerned Scientists who is based in Beijing, said the country is following an agenda that was laid out in the mid-1980s after the chaos of the Cultural Revolution subsided.

“They have very clear goals and a very clear agenda,” he said. “The Chinese aren’t racing anyone toward achieving those goals. Rather, they would like to be recognized for their contributions to space exploration.”

In 2003, China became the third country to send a human into space. The country has already launched 10 astronauts — or “taikonauts” — into outer space and has a test lab in orbit. It hopes to open its own space station in 2020 — the same year that the International Space Station is scheduled to shut down and de-orbit.

The Chinese government is building a 3,000-acre space center on Hainan Island in the South China Sea that will be capable of handling a new, more-powerful line of rockets. When the facility is finished, it will be the country’s fourth launch facility.

On Saturday, China became only the third nation to “soft land” on the lunar surface. The other two? The U.S. and the Soviet Union.

Frank Slazer of the Aerospace Industries Assn. trade group, said he expects that many of the exciting things in U.S. spaceflight will be done by private “new” space companies such as Hawthorne rocket maker Space Exploration Technologies Corp., or SpaceX, and British billionaire Richard Branson’s space tourism venture Virgin Galactic.

The government has done a good job of helping these firms along but needs to spend more in order to further push technological boundaries and inspire a generation of youth to pursue careers in science and technology, Slazer said.

“We have great aspirations, but we’re not adequately funding programs,” he said. “If we’re not careful, we could take our leadership in space for granted.”