California legislation would tighten rules on Internet sales tax

Mindy Benham knows how to pinch a penny.

That’s why the Costa Mesa resident does a lot of her shopping on the Internet. She particularly favors Amazon.com Inc. because the giant e-retailer doesn’t collect California state sales taxes on her purchases.

“There’s something about Milwaukee, where I’m from, that people take pride in how little they pay for something,” said Benham, a magazine art director, who recently bought a pair of eyeglasses and a sofa online. “I don’t want to pay taxes on something if I don’t have to pay taxes. If I can save a couple of bucks, I’ll do it.”

Benham’s frugal ways are shared by millions of shoppers nationwide, whose enthusiasm for tax-free Internet purchases has driven up e-commerce sales 300% over the last eight years. In-store purchases rose about 120% in that time.

That tax-free ride, though, could be running out of gas.

For the third time in three years, California lawmakers are pushing for legislation to make it harder for Internet sellers to avoid collecting sales taxes, and prospects for getting it passed are stronger than ever.

Passing the bill is a question of “e-fairness,” said Assemblywoman Nancy Skinner (D-Berkeley), who is sponsoring one of several Internet sales tax bills.

It also would put an extra $300 million into the state’s depleted coffers in its first year as a law, Skinner said, and would add California to the growing group of states creating their own Internet sales tax rules.

“Out-of-state online retailers designed their business model to avoid collecting sales tax,” she said. “This puts our Main Street businesses, which play by the rules, at a competitive disadvantage. It’s not fair to hurt California businesses that are struggling to keep their doors open.”

Rosemary Rodd, owner of Leo’s Professional Audio in Oakland, said her retail prices for high-tech mixing boards, synthesizers, speakers and guitars are as low or lower than the best Internet deals — before taxes.

But because her online competitors don’t collect sales tax and often provide free shipping, they are able to undercut her by nearly 10%.

“We get people who come in here and try the thing out and talk to my people about what works best for them,” Rodd said. “Then they buy it on the Internet and tell me, ‘I’m a musician. I’m broke. The $200 I saved was just too much.’ ”

What’s more, she noted, out-of-state competitors don’t support local charities or help pay for police and fire protection, schools, road repairs and other government services.

Skinner’s bill, AB 153, is based on a 2008 New York law that so far has survived court challenges. New York is leading more than a dozen states’ efforts to put retailers that sell through clicks online on a level playing field with those that sell through bricks and mortar.

Some states refer to proposed legislation as “Amazon bills” because Amazon, the Internet’s biggest retailer with $13 billion in revenue in last year’s fourth quarter, has opposed state sales tax collection measures.

Amazon and other Internet sellers have argued that the New York law violates the U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause, which gives Congress the power to regulate commerce among the states, as interpreted by a 1992 U.S. Supreme Court decision.

The court ruled then that it would be too burdensome to require out-of-state retailers to collect sales taxes, except in states where they have a “physical presence,” such as a store, warehouse, marketing call center or office. Since then, Congress has failed to come up with a uniform sales tax plan that could be applied nationwide.

Skinner’s proposal is supported by major corporations, including Wal-Mart Stores Inc., Target Corp., Best Buy Co. and Barnes & Noble Inc., as well as thousands of small bricks-and-mortar businesses, such as independent bookstores and clothing boutiques.

“This is not a new tax. It’s a collection issue,” said Bill Dombrowski, president of the California Retailers Assn.

Opponents also are a formidable lot. They include major online retailers Amazon, EBay Inc. and Overstock.com Inc., as well as about 25,000 affiliated website marketers that earn commissions by referring sales to the big online retailers. Those affiliates attract potential business by offering discounts and other deals when viewers click on icons to go to retail sites.

“To try to force a marketer not located in the state to learn the tax rates for 7,500 jurisdictions within the United States would constitute a burden on interstate commerce,” said Jerry Cerasale of the Direct Marketing Assn., an Internet, television and catalog sales trade group.

Opponents contend that any effort by California to tax Internet sales would backfire by harming small, start-up Internet companies — mainly, those affiliate marketers.

“Tax barriers that block small business from using the Internet will stifle job growth, reduce competition for retail giants and undermine entrepreneurial small business trying to spur economic growth,” said David London, EBay’s director of U.S. government relations.

Amazon, which opposes Skinner’s bill, and Google Inc. and Yahoo Inc., both of which opposed past Internet sales tax legislation in California, declined to comment.

The state has long had a back-up tax. A 35-year-old statute requires both businesses and individuals to pay a use tax on purchases when sales taxes aren’t collected. While businesses have shown spotty compliance, individuals almost universally ignore the use tax, experts said.

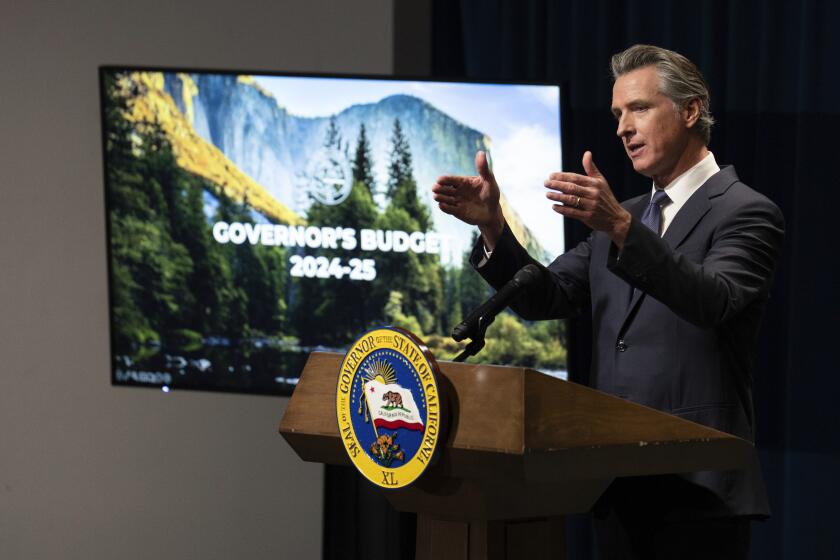

Democrats, who control both houses of the Legislature, are expected to approve Skinner’s bill. And Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown may not be able to say no to a source of new funds to help him fill a $25-billion budget hole.

Over the last decade, the National Conference of State Legislatures has persuaded 24 states, including Georgia, Michigan, New Jersey and Ohio, to join the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement. The agreement sets uniform tax definitions and administrative procedures that could become the foundation for a sales tax compact among the states, should Congress agree.

A University of Tennessee study estimates that states will miss out on about $10.1 billion in tax revenue from online purchases this year, and California will be the biggest loser with $1.7 billion going uncollected. Proposed statutes would recoup some but not all of that amount because, under the Supreme Court ruling, out-of-state Internet merchants can’t be required to collect the taxes if they don’t have offices or affiliates in the state.

But both national and state lawmakers might be ready to get their hands on more of the uncollected sales taxes to ease massive budget deficits.

“This could be ripe in Congress,” said Neal Osten, the conference’s federal affairs counsel. “Congress could give the states [the money] without having to find a dime to pay for it.”

If sales tax collections are going to be required, online retailers such as Overstock and Amazon would prefer that one set of national rules be adopted, rather than state-by-state laws, Osten said.

Meantime, more states are considering their own version of the New York law.

“I do think that we will reach a point of critical mass of states wanting to put this tax responsibility on e-tailers,” said Betty Yee, a member of the California Board of Equalization. “Consumers should not bear the responsibility to calculate the tax they owe and give it to the state. The people from whom they buy should calculate it for them.”

New York contends that online retailers already have the court-required bricks-and-mortar presence through their networks of in-state affiliates. Rhode Island and North Carolina, which passed their own New York-style laws, agreed. Late last year, the Illinois Legislature passed a similar measure, which is awaiting the governor’s signature.

In Texas, revenue officials last year handed Amazon a $269-million bill for back sales tax, contending the company owed the money because it operated a suburban Dallas distribution center. Amazon has since announced it will close the facility April 12 because Texas has an “unfavorable regulatory climate.”

Colorado may have gone too far by passing a law that requires Internet sellers to report information about their customers’ purchases to state tax officials. A federal judge issued a preliminary injunction Jan. 26 to halt enforcement of that law.

The judge’s ruling buttressed Overstock’s contention that various states “can’t make an out-of-state company be your tax collector,” said Overstock’s president, Jonathan Johnson.

Overstock would immediately sever its ties with California marketers rather than be forced to collect sales taxes based on any single state’s law, Johnson said.

“We ended them in New York, Rhode Island and North Carolina, and it hasn’t hurt our sales,” he said. “People like to find coupons and deals from affiliate marketers. If they don’t find them from a Los Angeles- or San Bernardino-based affiliate marketer, they’ll find them from somebody in Dallas or San Antonio.”

The affiliates fear they’ll lose a big part of their revenues if Overstock, Amazon and others cut them off as the retailers have threatened to do should California pass an Internet sales tax law.

“Roughly 15% to 20% of my business would go away. I’d have to lay off my workforce,” said Loren Bendele, owner of Savings.com, a West Los Angeles website that links viewers to hundreds of money-saving deals. “It would make me think, ‘Is California the right place to operate my business?’ ”

Ken Rockwell of San Diego, the owner of a 12-year-old photography website, Kenrockwell.com, predicted he’d lose 90% of his income if he lost his affiliate status.

“I happen to be in California,” he said, “but I can do what I do if I move to Tahiti or the south of France.”