Dairies Moving Out of Inland Empire

Once home to one of the nation’s largest concentrations of dairy farms, the Inland Empire’s $500-million dairy industry is rapidly evaporating as dozens of farmers sell out to real estate developers.

In the last two years, more than 160 dairies — nearly 80% of those operating just a year ago — have either been sold or are in escrow, according to the Milk Producers Council, a trade association based in Chino.

The industry could be virtually gone within five years. The pace of sales has accelerated as land values in the region have soared.

“There is not a dairy left that has not had a significant number of developers knocking on the door trying to buy it,” said Randall Lewis, executive vice president of Lewis Operating Corp., a developer in Upland.

The dairy lands of San Bernardino and Riverside counties make up some of the largest undeveloped tracts in metropolitan Southern California.

Developers are offering $400,000 to $500,000 an acre, and sometimes more, for land farmers purchased decades ago at just a fraction of that price. Five years ago, the same land sold for $50,000 to $100,000 an acre, Lewis said.

“The money is in the land, not the cows,” said dairy farmer Jean Gastelluberry, who purchased his first 20 acres of pasture in Ontario 36 years ago for $160,000.

To be sure, farmers fleeing urban sprawl is nothing new.

“People and cows don’t mix,” said longtime dairyman Bill Van Leeuwen.

But the speed with which the milk industry is leaving the region — turbocharged by large jumps in land values in recent years — is surprising even to longtime area dairymen such as Van Leeuwen.

And unlike previous cycles, dairy farming is leaving Southern California for good as milk producers move to Fresno, Kern, Kings and Tulare counties, and even as far as New Mexico and North Texas.

Open land, the proximity of large, milk-hungry cheese and ice cream plants in the San Joaquin Valley and the ability to sell off fertilizer to crop farmers have turned those counties into the nation’s milk shed.

In Ontario, Gastelluberry spends $240,000 annually to have the manure from his 2,500-cow herd hauled away because there are no nearby farms that can use the waste.

“We have lost 41% of our Southern California milk in the last three years,” said Gary Korsmeier, chief executive of Artesia-based California Dairies Inc., a farmer-owned cooperative that markets almost half of the milk produced in the state.

That milk is being replaced by shipments from the growing dairies in the San Joaquin Valley, he said. But because of the way milk prices are regulated in California, the northward shift in production isn’t expected to add to the wholesale price of milk, he said.

Most of the Inland Empire dairymen are the descendants of Dutch and Basque immigrants who settled in what is now Cerritos, Artesia and Paramount starting in the 1920s. Almost five decades ago, a younger generation started the migration to the Inland Empire as the last pastures in Los Angeles County gave way to housing tracts, shopping centers and, later, auto malls.

There still are dozens of dairies with names such as D&S Vander Schaaf Dairy — a windmill and two statues of kissing Dutch children decorate the entrance — and Rioseco Dairy lining either side of Schaefer Avenue as it heads east from Chino into Ontario.

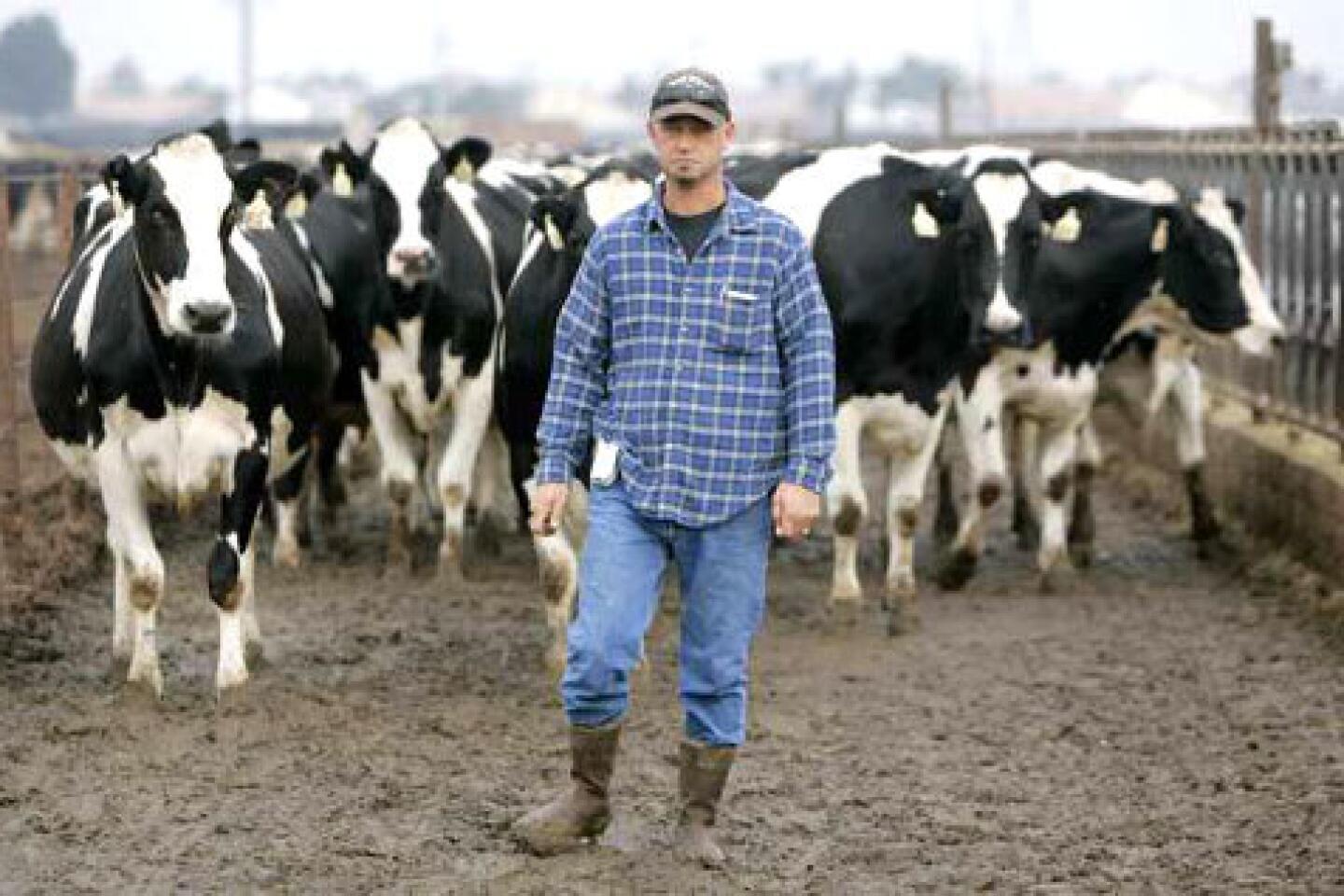

Hundreds of black-and-white Holsteins jostle each other almost up to the street and many of the farms have signs hanging out front offering “Free Fertilizer.”

For residents new to the area, it is impossible to miss the presence of the dairy industry. The smell of manure hangs in the air. On Riverside Drive in Ontario, residents looking out the windows of their stucco homes see Holsteins across the street. Errant shots on goal by soccer players at Colony High School have a good chance of hitting cows at the dairy next door.

At one point in the late 1980s about 400 dairies called San Bernardino County home, making it the largest milk producing county in the nation, said Nathan de Boom, the Milk Producers Council’s chief of staff.

The Van Leeuwen family illustrates the generational trek to the Inland Empire.

Bill Van Leeuwen’s grandfather moved to Paramount from the Netherlands in the late 1920s, opening a small dairy where he milked 60 cows by hand each day.

The next generation purchased 17 acres in Norwalk in 1945 where Bill Van Leeuwen helped his father care for a herd of 180 cows, and the family had upgraded to mechanical milking. The family’s milk was sold to the old Arden Farms brand.

But the post-World War II building boom made Van Leeuwen’s father feel fenced in and he sold the dairy land for $17,000 and moved to Chino in 1957.

Two decades later and another move, Bill Van Leeuwen went out on his own, purchasing 131 acres in the Eastvale area of Riverside County, where he milked 1,600 cows. But as land values rose, the family saw yet another opportunity to sell and expand. Van Leeuwen sold 40 acres to a developer two years ago for more than $10 million.

Two of his sons, now the fourth generation of Van Leeuwen dairymen in Southern California, operate a 2,600-cow dairy in the Imperial Valley. A third son still runs a dairy in Riverside County. But the rented land has been sold, and he will have to move on in the next year or so too.

Dairy farmers “will say they were forced out by urbanization,” Van Leeuwen said. “But really we were enticed to leave.”

Lewis is one of those doing the enticing. In recent years, his company has purchased 30 dairies ranging in size from 20 to 250 acres.

Most of the acquisitions have been in an area now called The Preserve at Chino, where Lewis has more than 1,000 acres for a 7,300-home planned community.

“A big appeal of this real estate is that it is so close to the job centers and the freeways,” said Lewis, whose company continues to seek out more dairy land. “This is how you get scale.”

The open space is so desirable for building that developers put up with the extra expense required to convert former dairies to homes.

The biggest problem is figuring out what to do with the years of manure that have piled up on the sites.

Ontario requires developers to check for methane gas and to take soil samples throughout the sites. Sometimes, they have to haul away soils “with high organic content,” said Jerry Blum, the city’s planning director. They then have to bring in clean soil, mix it with the remaining dirt, then regrade and compact the earth.

The decline of the dairy industry has not hurt the region’s economy. Dairies account for about 2,000 jobs in the region, down from about 2,600 four years ago, according to the state Employment Development Department. The Inland Empire has generated 19,300 new jobs over the last 12 months. At the same time, the unemployment rate has dipped to 5% from 5.3% a year ago, the state agency says.

Construction employment has jumped 5.2% as retail centers, warehouses and homes take shape on former dairy land.

Nonetheless, the northward migration of the dairy industry is forcing vendors and suppliers left behind to diversify in order to survive.

Valley Equipment Co., a longtime supplier of milking and sanitation systems, has shifted its product mix to swimming pool toys, pool chemicals and spas. Dairy supplies fill up a small space in the back of its Euclid Avenue store in Ontario.

Owner Norm Zuidema Jr. still sells to dairies, but he is preparing for the day when they are gone, a likelihood that’s hard for him to miss.

The dairy that had been next door to Valley Equipment was closed down. It’s now a tumbleweed-strewn lot.

And Dairy Center Inc., on the other side of Zuidema’s store, now sells pet products.

“It scaring me to death,” Zuidema said. “Not all of us are going to make it through” this transition.

Through a quirk of geography, Bob Dejager, owner of Dairyland Hay Co. in Chino, said his business will survive, but not in its current form. It turns out that Chino serves as a midway point between the hay fields of the Imperial Valley and the Central Valley dairies.

Dejager will send his fleet of 50 trucks to collect the animal feed and haul it over the Tejon Pass to Bakersfield and Tulare.

And as the dairies move north, there’s going to be a greater need for trucks to move milk back to the urban areas, providing Dejager with more milk hauling opportunities.

Although he is losing local clients, Dejager stands to benefit because the state’s dairy business remains strong.

California produces a fifth of the nation’s milk and its market share is growing. It is also about to become the leading cheese-producing state, surpassing Wisconsin.

California has about 2,100 dairies, a 5% decline from five years ago. But the number of dairy cows has jumped 14%, to more than 1.7 million, during that same period as the average size of the dairy farms has grown.

“When these dairymen move, almost all of them grow because they reinvest the capital generated by the sale of the property into a bigger dairy,” said Korsmeier of California Dairies.

Although he sees all these trends, Gastelluberry, 70, says he’s one farmer who doesn’t plan to leave Ontario anytime soon: “There’s no reason to go anyplace else. I am going to retire from here.”

And when he does, “I will make 10 times in real estate what I did during a lifetime of dairy.”