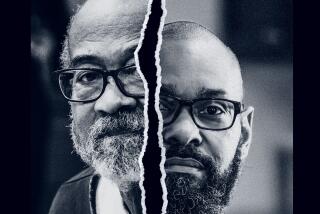

How I Made It: Wayne Bradshaw rose from humble beginnings to shepherd black banks through turmoil

Wayne-Kent Bradshaw, 71, is chief executive of Broadway Federal Bank, an institution he helped rescue from fraud and the recession. It’s now the last African American bank headquartered in the Western United States, and the probable last stop in a successful career that would have seemed unlikely as a teenager in Jamaica. Bradshaw says he has been guided by the firm belief that banking can be a force for good.

Island native

Born and raised in Kingston by a single mother, Bradshaw showed early promise. He took and passed a national exam that got him admitted to Wolmer’s, an august prep school that once was reserved only for the children of wealthy families. When he was 14, though, Bradshaw’s mother, Gloria, left Jamaica to find work in Los Angeles, where the job prospects were better. (She applied for a job at Broadway Federal, the bank Bradshaw now runs, but didn’t get the position.)

“I’ve been on my own essentially since I was 14,” he recounts. He lived with a few families — his mother had made arrangements and sent back money — and later with his paternal grandparents. Despite his aptitude, he didn’t take school seriously, was held back and even dropped out for a time. His life turned around after some of his teachers took him under their wing. “I got a lot of help. I was just that lucky kid everybody chose.”

Silver screen

When he was 19, he joined his mother in Los Angeles and started classes at L.A. City College. He had visited Southern California only once before, but the city nevertheless felt familiar — a result of Bradshaw’s love of cinema.

“I’m someone who lived in movie theaters — I still do,” he said. “That gave me a sanitized view of Hollywood, but still a pretty universal picture of L.A. In Jamaica, I lived next to an open-air theater where they’d show triple features — B gangster movies, shoot-’em-ups.”

One of his favorites, though, was “My Fair Lady,” the story of professor Henry Higgins and his quest to help cockney-accented Eliza Doolittle speak like a lady. The tale, adapted from George Bernard Shaw’s “Pygmalion” — itself rooted in Greek myth — contained for him a vital management lesson.

“The professor really believed in Eliza Doolittle — that she could be a lady with training. I’m committed to believing people can be really great. And people pick up on that. People don’t want to disappoint someone who believes in them.”

Motivating factors

After two years in L.A., he earned an athletic scholarship to the University of Arizona, where he ran the 400 meters and studied economics — a subject he felt naturally drawn to. “I’ve always had a tremendous interest in what motivates people, and it seemed to me that economics is a key motivating factor in most cases.”

He planned to continue studying economics and earn a doctorate, but took an interest in banking instead after working for Union Bank during his last summer in college. He started full time at Union Bank in 1970 and earned an MBA from USC, taking classes five nights a week.

He spent 17 years with Union Bank, but not all at once. He left for a few years to work for an engineering firm, then returned and left again to serve as chief deputy superintendent of the California State Banking Department. He went on to co-found Industrial Bank, a Van Nuys lender that was later acquired, before returning to Union Bank once more.

“Banking is a lot like economics. It just seems very, very natural to me. I like the idea of being someone who gets up every day and is allocating resources to help make a difference.”

More success stories from How I Made It »

Second chapter

In 1988, Bradshaw took the job that would change the course of his career: He took over Founders Savings and Loan, one of only a few black-owned financial institutions in Los Angeles at the time. It was on the verge of failure, losing millions of dollars a year and straining under the weight of bad loans.

Bradshaw helped clean up the bank’s books before it was sold to new investors. He quickly moved on to another black bank, Family Savings Bank in Crenshaw, that was also struggling. There, he helped clean up a troubled loan portfolio and also raised capital that helped the bank stay in business.

“The problem is always the same: You make bad loans and after a while those loans start to bleed away the value of the company. And the turnaround process is the same: You bring in talented people and start the repairs and come up with something that can sustain the institution going forward.”

No bag man

In 2003, when Family Savings was acquired by another bank, Bradshaw went to work for Washington Mutual as a community development executive, a role he kept after Washington Mutual was acquired a few years later by JPMorgan Chase.

He describes his role as being little more than a corporate “bag man.” Instead of working with the bank to make loans that would help improve communities, he said his marching orders were to give donations to community groups that might otherwise cause trouble for the bank.

“You’re more of a gatekeeper than a proactive change agent. You’re provided with resources to placate community organizations — ‘Here’s a check and some nice things you can say about us that will help us get a good rating from regulators.’”

So he left Chase in 2009 to join Broadway as president and chief operating officer. He turned out to be the right hire at the right time.

Unexpected turnaround

When he joined the bank, it was in good shape, despite the financial crisis. Broadway, founded in 1946 to make home loans to black Angelenos shut out by white banks, hadn’t been part of the subprime mortgage mess and its books looked good.

But as the recession worsened, the bank faltered, stung by a growing number of delinquencies on loans made to churches. Many of those loans were approved by a Broadway loan officer who, years later, pleaded guilty to accepting kickbacks from loan brokers in exchange for making loans that would not have met the bank’s credit standards.

Though his previous positions had been focused on turning around troubled banks, Bradshaw hadn’t been looking for that type of posting when he joined Broadway. But in 2012, Broadway needed saving and the bank’s board wanted Bradshaw to take over.

“I could be either CEO or unemployed. It turns out, after quite a stellar career, this is the best job I’ve ever had.”

Today, Broadway is healthy and profitable — and it no longer makes church loans. Instead, it lends to buyers of small apartment buildings in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods across Southern California. Those loans, Bradshaw said, help maintain a stock of affordable housing.

“We focus on the working poor and providing affordable living spaces for people. Having that kind of opportunity, I feel blessed.”

Jamaica drive

Bradshaw’s previous institutions, Founders and Family, were both acquired by Boston-based OneUnited Bank. That leaves Broadway as not only the last black bank based in Los Angeles, but the only one headquartered west of Dallas. Bradshaw said this will be his last stop, too.

“There are no more left, so I guess I’m at the end of my career.”

Bradshaw and his wife, Mary, herself a former bank executive, have two grown daughters: Kelley, an attorney in Northern California, and Christine, who graduated from USC in May and will start law school at UC Berkeley in August.

Bradshaw lives in Calabasas, which makes for a long commute to Broadway’s Mid-Wilshire headquarters, but he enjoys the drive. Instead of braving the 101, he takes Old Topanga Canyon Road to Pacific Coast Highway — a route that reminds him of his native Jamaica.

“It’s so beautiful and so bucolic — it’s a nice way to start the day. Then I turn onto the 10 freeway and it hits me: I really am going to work.”