U.S. health system has flaws, but not in quality of care

The healthcare system, like the government, is easy to criticize until you need it. And then it’s indispensable.

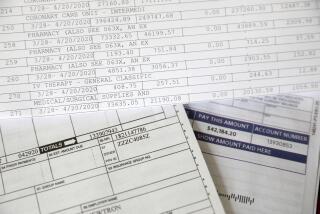

I’ve devoted my fair share of ink and digital bits to talking about what’s wrong with healthcare in the United States. I wrote last week about yet another example of loony billing practices.

Today, let’s appreciate some of the things that make our system extraordinary — maybe not the best in the world, as conservatives are fond of gushing, but pretty darn impressive.

My wife had a seizure a couple of weeks ago after the sodium level in her blood dropped dangerously low. She’s now home after spending eight nights in the intensive care unit at UCLA Medical Center.

I’ll keep details of this family matter private. But what I want to share are some observations based on having been at my wife’s bedside for much of her hospital stay.

First, it’s hard to imagine any other healthcare system in the world that can marshal as many resources as ours. From highly skilled doctors and nurses to every possible medical device and drug, our system is second to none in its capabilities.

No wonder that when foreign leaders fall sick, they often seek treatment here and not at home.

Moreover, once you’ve gained access to the higher levels of the system — admittedly, no small feat — there’s seemingly no limit to efforts that will be made to heal you. Every possible test will be run. Every expert opinion will be sought.

This is undoubtedly wasteful. But when it’s a loved one with his or her life on the line, is there anyone who would seriously cut corners if given a choice?

Ah, but there it is. None of this remarkable care comes cheap. And it’s how we price and bill for such services that makes our healthcare system, for all its merits, unworkable and unsustainable.

“We get what we pay for, and we have a payment system that pays for more,” said Stuart Guterman, vice president of Commonwealth Fund, a healthcare policy organization. “So we get more.”

Here’s an example: My wife told her nurse that she was having trouble going to the bathroom. The nurse didn’t hesitate. She wheeled in a fancy-looking gadget and did an ultrasound on my wife’s bladder to see whether there was any fluid in there. There wasn’t.

It’s unquestionably a good thing to know for sure whether a patient’s plumbing is functioning. It’s the difference between understanding whether she’s experiencing minor discomfort or a major medical issue.

But was the test necessary? Would it have sufficed to just wait and see? I have no idea.

How much did the test cost? Again, I have no idea. One hundred dollars? Five hundred? A thousand? Was it fully covered by our insurer? Partially covered? Not covered at all?

No clue.

As I sat in the ICU watching all the activity in my wife’s and other patients’ rooms, I wondered what it would be like if every treatment came with a price tag prominently displayed, as in any other retail environment.

What if that ultrasound bore a big sign declaring it to be a $500 exam? What if the MRI machine announced itself as a $4,000 experience? What if the mild sedative my wife requested to help her sleep was revealed to cost $100?

Would that change anything?

Perhaps there are some people who would forgo this or that treatment when presented with an actual price. But I think most people wouldn’t hesitate to accept whatever was offered, especially if your doctor believed it was in your best interest.

That’s what makes healthcare so unlike any other consumer product available. The typical shopper is fully capable of making informed decisions about whether to buy Nike or Converse sneakers, or which brand of jeans to wear, or what kind of car to drive.

But is there anyone without medical training who feels qualified to say, “No thanks, we’ll skip that bladder ultrasound and see what happens?”

“Consumers are the last people to make these decisions,” said David Dranove, a healthcare economist at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management. “Nobody should try to play doctor.”

It’s crazy to think that patients will ever be in a position to be equal partners in the healthcare equation. This is the one product in which we have to trust others to be looking out for us.

Yet, along with being caregivers, those others are representatives of financial interests that are mindful of how people’s medical treatment will affect their bottom line.

That’s not to say hospitals, drug companies, medical device makers and even insurers aren’t having a positive effect on society. They are. But they’re also businesses. They measure their overall success not in lives saved but in dollars earned.

As such, it’s important that our healthcare system have the transparency and oversight required to keep patients, not profits, front and center.

The healthcare marketplace doesn’t foster the same economic forces that keep other markets in line. Consumers aren’t making free decisions. Medical businesses exploit their unfair advantage in the form of arbitrary and hidden prices.

Americans pay twice what people in other developed countries pay for healthcare. Yes, we have the best tools. Yes, we have the best medical practitioners.

And, yes, I wouldn’t want my wife to have been treated anywhere else.

But I live in fear of the bill that’s coming down the pike. It will almost certainly run in the six figures. My out-of-pocket costs could run to five figures.

More than 60% of personal bankruptcies in this country are caused by medical bills, according to researchers at Harvard Medical School. And of those who file for bankruptcy, 78% have health insurance.

I’m grateful for the exceptional care my wife received. Our healthcare system is truly a marvel.

Yet I have to ask: What’s the good of having the best tools if no one can afford to use them?

David Lazarus’ column runs Tuesdays and Fridays. He also can be seen daily on KTLA-TV Channel and followed on Twitter @Davidlaz. Send your tips or feedback to david.lazarus@latimes.com.