Doctors and hospitals posing as charity cases? It’s nauseating

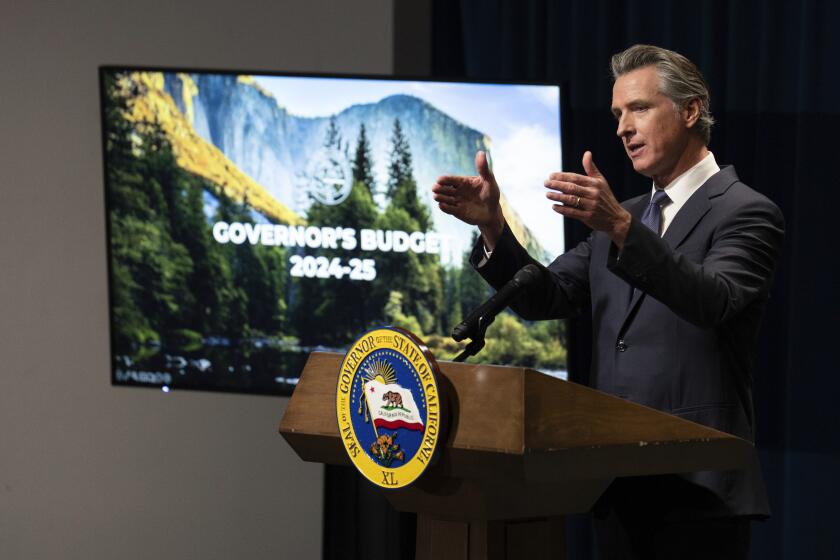

Obamacare was intended, in part, to rein in sky-high healthcare costs.

Yet some doctors and hospitals are responding to the reform law with outstretched palms and brother-can-you-spare-a-dime pleas for more money from patients.

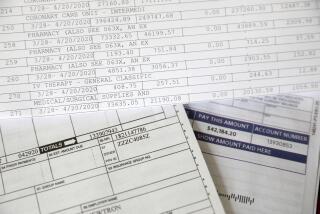

Evelyn Stern, 75, of Brentwood has been treated at UCLA Medical Center for the last few years and always has appreciated the hospital’s gleaming facility and state-of-the-art resources.

“They don’t seem to be hurting for money,” she told me.

So Stern was more than a little surprised to receive a recent solicitation for voluntary donations from the hospital’s Division of Geriatrics.

It included a helpful form with boxes to check for contributions of as much as $10,000. Patients donating at least $1,000 will be listed as “Friends of Geriatrics” and will be invited to a special “donor recognition event hosted by doctors and key faculty members.”

“I get it if the L.A. Philharmonic sends you a letter to support the orchestra,” Stern said. “It’s a little peculiar when you get such a letter from someone you rely on for your well-being.”

It’s hard to imagine UCLA Medical Center giving preferential treatment to a financial “friend” of the hospital. At the same time, some patients might wonder whether there could be repercussions for not ponying up a little baksheesh.

Dr. David Reuben, head of UCLA’s Division of Geriatrics, defended the fundraising effort.

“With federal research dollars and state funding more and more scarce and an aging population, philanthropic support is crucial to fulfilling our mission,” he said.

Roxanne Moster, a spokeswoman for UCLA Health Sciences, said the letter was worded to “ensure there can be no perception that donors are given any different level of care or treatment than non-donors.”

If so, I didn’t see any explicit reference to such a sentiment. I did see, though, where the Division of Geriatrics says it’s launching a new online service, “and an endowment will enable us to name it after you or any person you choose.”

There’s no question that Obamacare can make things tougher for healthcare providers. Tens of millions of new patients are entering the system, many with Medicaid — Medi-Cal in California — coverage that limits reimbursement to doctors and hospitals.

Dr. Dike Drummond, whose Seattle company, TheHappyMD.com, focuses on reducing physician burnout, said many doctors are bracing for “a tidal wave of new patients” and financial pressure to see as many as 30 patients a day to make ends meet.

As a result, he said, an increasing number of doctors are abandoning the conventional insurance system and are switching to so-called concierge practices.

Such practices enable doctors to see fewer patients, but those patients are often required to pay steep annual fees — separate from their medical costs — in return for more comprehensive treatment.

The upshot is a two-tier system in which those who can afford quality healthcare pay for the privilege, and everyone else settles for long waits to see overworked doctors or, if the doctor is too busy, a nurse practitioner.

“As a doctor, I might feel a pang of guilt about making a change like this,” Drummond said. “But it’s my life, and I want to practice medicine the best way I know how.”

Other doctors are trying to walk a middle path.

Dr. Jeffrey S. Helfenstein, a Beverly Hills cardiologist, recently sent a letter to patients saying, “I am sure you are all aware of the changes in medical reimbursement to physicians that are contracted to Medicare and other common insurance carriers.”

He said he considered switching to an “expensive concierge medical practice” or “total cash fee for service.”

Instead, Helfenstein said, he’s decided to have patients pay a “small office fee” of $350 a year to cover everything that insurers won’t pay for, such as extra paperwork and speaking with patients on the phone.

Helfenstein didn’t return calls for comment.

I sympathize with doctors who find themselves buried in bureaucratic nonsense related to dealing with dozens of insurers, each with a different way of doing business.

And if I were in their position, I’d also be unhappy about being paid less because of lower reimbursement rates, even though a 2012 study found that doctors are one of the largest groups in the top 1% of rich people in the United States, along with business executives and lawyers.

A separate study last year by the Medical Group Management Assn. found that median compensation for primary care physicians in this country was $216,462. Median pay for specialists was $388,199.

Are U.S. doctors paid too much? It’s all relative. Compared with movie stars and athletes, no. Compared with most other working stiffs, kind of.

A 2011 study by the consulting firm McKinsey found that general physicians in other developed countries — most of which have government-run insurance systems — earned double what the average worker made, and specialists earned 2.7 times as much.

In the United States, according to McKinsey, primary-care doctors earned five times as much as the average worker and specialists earned 10 times as much.

“The United States would have spent $120 billion less in 2008 if U.S. physicians were compensated in the same proportion to the national average worker as their counterparts in other developed countries,” McKinsey concluded.

Meanwhile, a recent study by researchers at Harvard University found that average compensation for chief executives of U.S. nonprofit hospitals runs about $600,000 a year. Annual pay for CEOs of big-city hospitals can be in the millions of dollars.

I don’t begrudge doctors and hospital execs for trying to maintain the income levels to which they’ve grown accustomed. But at some point, they’re going to have to be part of the solution and not part of the problem.

Americans already pay more for healthcare than anyone else in the world. Hitting patients up for even more money isn’t just counterproductive — it’s offensive.

David Lazarus’ column runs Tuesdays and Fridays. He also can be seen daily on KTLA-TV Channel 5 and followed on Twitter @Davidlaz. Send your tips or feedback to david.lazarus@latimes.com.