Give the doctor a checkup before ordering a house call

He refers to himself as Dr. House Call. In glossy brochures mailed recently to thousands of well-to-do households from Malibu to Brentwood, he said he was seeking to be a “caring, old-fashioned Marcus Welby kind of good doctor without the office hassles.”

Dr. House Call -- a.k.a. Dr. Herbert Rubin -- is an example of a small but growing trend in medicine as physicians cut themselves free from insurance companies and enter into direct relationships with patients who can afford more personalized healthcare.

He’s also an example of why people may want to shop around before inviting a so-called concierge physician into their homes. Although his brochure doesn’t mention it, Rubin is on probation with the Medical Board of California for accusations that include gross negligence, incompetence and insurance fraud.

“Accusations have been made,” he told me over coffee the other day at a Pacific Palisades restaurant near his home. “I absolutely deny them. They were all false.”

No one knows precisely how many concierge practices exist nationwide. Neither the American Medical Assn. nor the American College of Physicians keeps such data, but healthcare professionals peg the number at fewer than 1,000 and growing as doctors seek alternatives amid rising costs and cutbacks in reimbursement by insurers.

In most cases, a concierge physician chooses to limit his or her practice to only a few hundred patients, rather than the usual 2,000 or 3,000. Patients may pay the physician an annual retainer that can run as high as $15,000 or an hourly fee of hundreds of dollars, on top of whatever costs may accrue as a result of treatment.

Critics of concierge medicine point out that such practices generally target the wealthy and create a tiered system whereby people who can afford it get first-class medical treatment, and everyone else gets what they get.

Proponents say concierge physicians offer a legitimate service and charge only what the market will bear.

The American Medical Assn. says what it calls retainer practices “are consistent with pluralism in the delivery and financing of healthcare.” However, the industry group also warns that such practices “raise ethical concerns,” particularly if they “become so widespread as to threaten access to care.”

“All patients are entitled to courtesy, respect, dignity, responsiveness and timely attention to their needs,” the association says.

Rubin, 67, has been practicing medicine since 1975. Much of that time was spent in Beverly Hills, where he focused on gastroenterology, or matters related to the digestive system.

Rubin said he decided around 2000 to stop dealing with insurers. They were more trouble than they were worth, he said, and interfered in his dealings with patients.

In 2006, Rubin said, he concluded that it was time to retire from medicine. “It stopped being fun,” he said. “I loved the patient-care part. But all the rules, regulations, restrictions -- I didn’t want to do it any more.”

But after a year pursuing other interests, Rubin said he missed practicing medicine. He saw that many physicians who shared his frustrations with the healthcare system had turned to concierge practices.

Dr. House Call was established about eight months ago. First Rubin set up a website. Then he started sending his brochures to about 15,000 Westside households selected by a marketing firm for their high income or property value.

No prices are listed in the brochure. But Rubin’s website, Doctorhousecall.md, says he charges $450 for most new-patient visits, $300 for follow-up visits, $400 for hospital visits and $250 for telephone consultations. “I now have about 150 patients,” Rubin said, smiling. “I only need to see one or two patients a day to be in the black.”

His face fell when I asked about his troubles with the Medical Board. Rubin described the matter as “billing questions” and called it “ancient history.”

The board’s accusation says that, among other things, Rubin failed to follow up on a patient he sent to a hospital in 2002 for colitis, a gastrointestinal disorder, and failed to arrange for another doctor to care for the patient while Rubin was out of town.

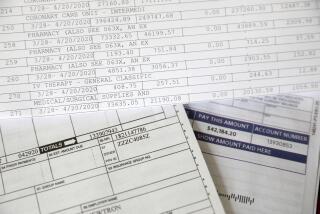

It says he failed to release a patient’s medical records to another physician in 2001 and billed patients and insurance companies for the same treatment. The accusation also says Rubin “billed for tests that were not rendered or were not documented” and “medical visits, a surgery, supplies and X-ray or lab services that did not occur.”

In his June 2005 settlement with the agency, Rubin stipulated that although he did not admit that the accusations against him were true, he acknowledged that the board could make a strong case against him if the matter proceeded to a hearing.

Rubin was placed on probation for five years and was required to take courses on ethics and record-keeping. He is permitted to continue practicing in California and is not required to disclose his probationary status to patients.

After the settlement was reached in California, Rubin was forced to surrender a separate New York medical license, preventing him from practicing in the state. He also had his medical privileges terminated by Brotman Medical Center in Culver City, requiring Rubin to rely on other doctors in the event that a patient is hospitalized there.

Out of 125,000 physicians licensed by California, Rubin was one of only 92 placed on probation in the fiscal year that ended June 2007, according to Medical Board figures.

I asked Rubin how he could have been accused of filing false claims to insurance companies if he’d stopped dealing with insurers in 2000. He told me the state’s investigators had their facts wrong.

Debbie Nelson, a spokeswoman for the Medical Board, said the board stood behind its findings in the accusation.

I also asked Rubin why he settled with the board and agreed to the terms of his probation if the accusations against him were false.

“A lot of doctors settle rather than fight,” he replied. “Doctors have been bankrupted by lawyers. Doctors are at the mercy of any accusation the Medical Board makes.”

As for his new gig as Dr. House Call, Rubin said he’d already received calls from other physicians asking for advice on setting up their own concierge practices. He described the healthcare system as “a slow-motion train wreck” and said that “the only doctors left will be the ones whose practices are one on one.”

“I don’t think healthcare is a right,” Rubin said. “It’s a service like any other service.”

And like any other service, the old saw applies: Buyer beware.

To check the status of any licensed physician in California, go to the Medbd.ca.gov website and click on “Check Your Doctor.”

Consumer Confidential runs Wednesdays and Sundays. Send your tips or feedback to david.lazarus@latimes.com.