Grand Rapids boasts the large manufacturing sector Trump wants, but is it a model for the nation?

For a metropolitan area of about 1 million people, Grand Rapids has retained the open, friendly feel of a small town, with the tree-lined streets and well-kept houses common in the Midwestern heartland.

It also has what may be a more important distinction, something President Trump says the whole country needs: manufacturing jobs — lots of them.

Fully 20% of workers here make things. That share of manufacturing jobs is more than twice the national average.

Grand Rapids is hardly the land of “rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones” that Trump evoked in his inauguration address.

Manufacturing has helped drive unemployment down to less than 3%, below the U.S. average, and a shortage of workers has led employers to raise starting pay, even to offer signing bonuses and give jobs to ex-offenders. That’s one reason the share of people working or looking for work here was nearly 69% last year, much higher than the nationwide average.

But neither is Grand Rapids a model for the rest of the country. For all its successes, wages overall remain relatively low on average – well below where they were when U.S. manufacturing dominated world markets.

And manufacturing here seems to have had a limited ripple effect. Four out of 10 households cannot afford to cover basic necessities such as housing, food and healthcare, according to a detailed United Way study updated this year.

It raises questions about the viability of Trump’s plan to fuel economic growth by returning the manufacturing sector to its heyday, and it leaves unresolved a fundamental problem of the modern-day American economy: how to provide stable jobs that pay enough to let workers live modestly comfortable lives.

“If you’re looking for overall economic well-being, the path to prosperity is no longer factories,” said Lou Glazer, president of Michigan Future, a nonpartisan think tank in Ann Arbor.

Of the nation’s 52 metro areas with a population of at least 1 million, he notes, Grand Rapids is No. 1 in manufacturing as a percentage of overall employment. But it’s in the bottom five when it comes to income per resident.

“You don’t want the rest of the country to look like this,” he said.

Even so, the Grand Rapids area remains home to some big manufacturers that have shown a high degree of creative flexibility and willingness to adapt to challenges in the global economy. Among them are Haworth Inc., a $2 billion firm in nearby Holland that makes office furniture. It not only survived the Great Recession but came out stronger, more focused on contemporary design and customizing workspaces for companies.

“We don’t make widgets,” says Franco Bianchi, Haworth’s chief executive, using shorthand for old-fashioned manufacturing that focused on mass production of a single item or product – an approach that is often not nimble or flexible enough to meet the needs of rapidly changing consumers. Haworth employs 2,700 in the area.

Grand Rapids also boasts smaller industrial firms that use imaginative ways to meet the challenges they face.

Wolverine Coil Spring Co. has been family-owned since 1946. Today it is more diversified than in the past, making parts for rear-view mirrors, dishwasher doors, office chairs, blood-circulation machines.

But Wolverine’s president, Jay Dunwell, worries about the prospect of labor shortages down the road, considering the already low unemployment. So the 52-year-old executive has gone on the road himself.

He visits schoolchildren to talk up careers in manufacturing. To catch their interest, he uses some of Wolverine’s old products – grenade casings and ashtrays with springs inside to hold cigarettes.

Dunwell, like many other employers, has also responded to low unemployment by offering better pay. But even so, the median hourly rate for production work in the Grand Rapids area — the midpoint where half make more and half less — was $14.51 last year, or about $30,000 a year.

That was no better than the earnings for workers in sales occupations, and it was about $2 an hour less than what office and administrative-support jobs paid, according to Michigan labor statistics.

That’s a stark change from the past, when manufacturing jobs on average paid significantly more than sales and lower-level white-collar jobs.

The median pay for all workers in the area was $16.41 an hour. That translates into roughly $34,000 a year.

As in most of the country, the causes include global competition, mechanizing and outsourcing, and a decline in unions — though unions were never as big in western Michigan as they were in Detroit and other industrial centers to the east.

Glazer of Michigan Future noted that the two biggest factors driving economic prosperity nationally are college education and the proportion of knowledge-based services in the local economy.

Grand Rapids is below average on both counts. As in Pittsburgh, Cleveland and other traditional bastions of industry, what’s growing fastest are healthcare and business services, which employ many salaried professionals but also large numbers of relatively low-skilled, less-educated and less well-paid workers.

“If you care about people’s ability to pay their bills, you’ve got to figure out how to get them into high-wage work, and factories are not high-wage work,” Glazer says.

There are high-wage jobs in manufacturing, of course, but these increasingly require a college degree or special skills. For the 81,200 production workers in the Grand Rapids area, only 10% earned more than $25.13 an hour last year, or about $52,000 a year, according to the Michigan Bureau of Labor Market Information.

Factory worker Ross Tenharmsel, 32, says manufacturing is in his blood.

His grandfather retired from a General Motors body plant that once operated in the Grand Rapids area. Some 15 years ago, straight out of high school, Tenharmsel followed his father into the factory at RoMan Manufacturing, a maker of transformers for the auto industry and other customers.

He started out at RoMan making $10.50 an hour and now earns a little more than double that doing pretty much the same job he did at the beginning: working the brazing torch. He stands at a spartan work station, where he keeps one small photo of his stay-at-home wife and two young daughters, 4 and 1.

He’s been able to break into the top 10% of earners for production workers, sharply boosting his standard of living, but only by putting in a lot of overtime. During one stretch last year, he worked 60 hours a week for nine straight weeks. Altogether, he pulled down $70,000 last year, enough to sock away a little after paying the mortgage on his custom-built house and other bills.

It helped that, as with many other places in the Midwest, living costs here are modest. A resale home in the Grand Rapids area fetched a median price of $164,000 in the first quarter, versus $232,000 nationally. A gallon of milk costs $2 at a local Meijer supermarket, a buck less than the U.S. city average.

“It’s a business you’re not going to get rich in, but if you play your cards right, you can make a decent living,” Tenharmsel said. And he still gets a lot of satisfaction at his job, taking pieces of parts and turning them into something. “At the end of the day, I feel productive,” he said.

Overtime is one way manufacturers have dealt with the dwindling labor supply. Companies like RoMan, which employs 140 people, also have been raising wages in the last couple of years, but most manufacturing firms, small and large, are still offering $11 to $13 an hour to start for basic production work like machine operators.

Many manufacturers are doing what they can to draw and keep employees without raising wages more. Flexible work hours mean Wolverine Coil Spring’s managers have to juggle multiple schedules on the first shift to give more workers a shot at the more desirable work hours.

Dunwell said the company’s been more generous with bonuses and time off, and is trying to create a more inviting work culture by sponsoring weekly walks and monthly games and contests.

He acknowledges that living on $12 an hour, the firm’s starting pay for production work, “is going to be very challenging,” but says labor rates are dictated by what the market will bear.

“When those are the cards that are dealt, you have to be cost-conscious,” he says.

Despite the limits of manufacturing jobs, industry continues to have a powerful hold here.

For nearly a century Grand Rapids was the nation’s center of home-furniture manufacturing — attracting Dutch, Polish and other immigrants from Europe -- until western Michigan pretty much ran out of lumber and the industry moved to North Carolina by the 1960s.

The Grand Rapids area is still tops in office furniture, and it remains a major supplier to the state’s auto industry. Amway, which is based in Grand Rapids and plays a leading role in the region’s economy and revitalization of downtown, has a large manufacturing plant in Ada, a suburb.

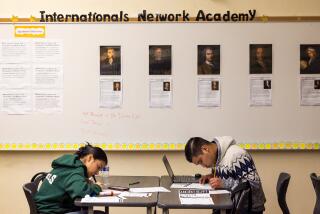

Kathy Crosby, president of Grand Rapids’ Goodwill Industries and 37-year veteran of the nonprofit job-training services, is thankful for the area’s strong industrial sector. She calls manufacturing “comfort food” for a region that believes in making things with your hands. And she says the labor shortage is opening doors into factories, some with career paths, for more low-skilled workers and those on the margins of the economy.

Yet Crosby isn’t counting on manufacturing, either. Like many experts, she thinks automation will continue to curb job growth. Even if industries keep growing in places like Grand Rapids, she doesn’t see the glory days of manufacturing coming back — the days when her father, who went no further than the seventh grade, made a handsome living working in GM’s plant in Pontiac, Mich.

So she and her staff are trying to help workers to go beyond manufacturing, to raise their skills and earn certifications in healthcare, for example. For many in this manufacturing stronghold, Crosby said, the question is the same: “How are we going to lift wages so the entire community can move forward?”

Follow me at @dleelatimes

ALSO

Trump attorney signals a firm stance in dealing with special prosecutor

A new generation of Democrats isn’t waiting for the party to tell it what to do