Automation is increasingly reducing U.S. workforces

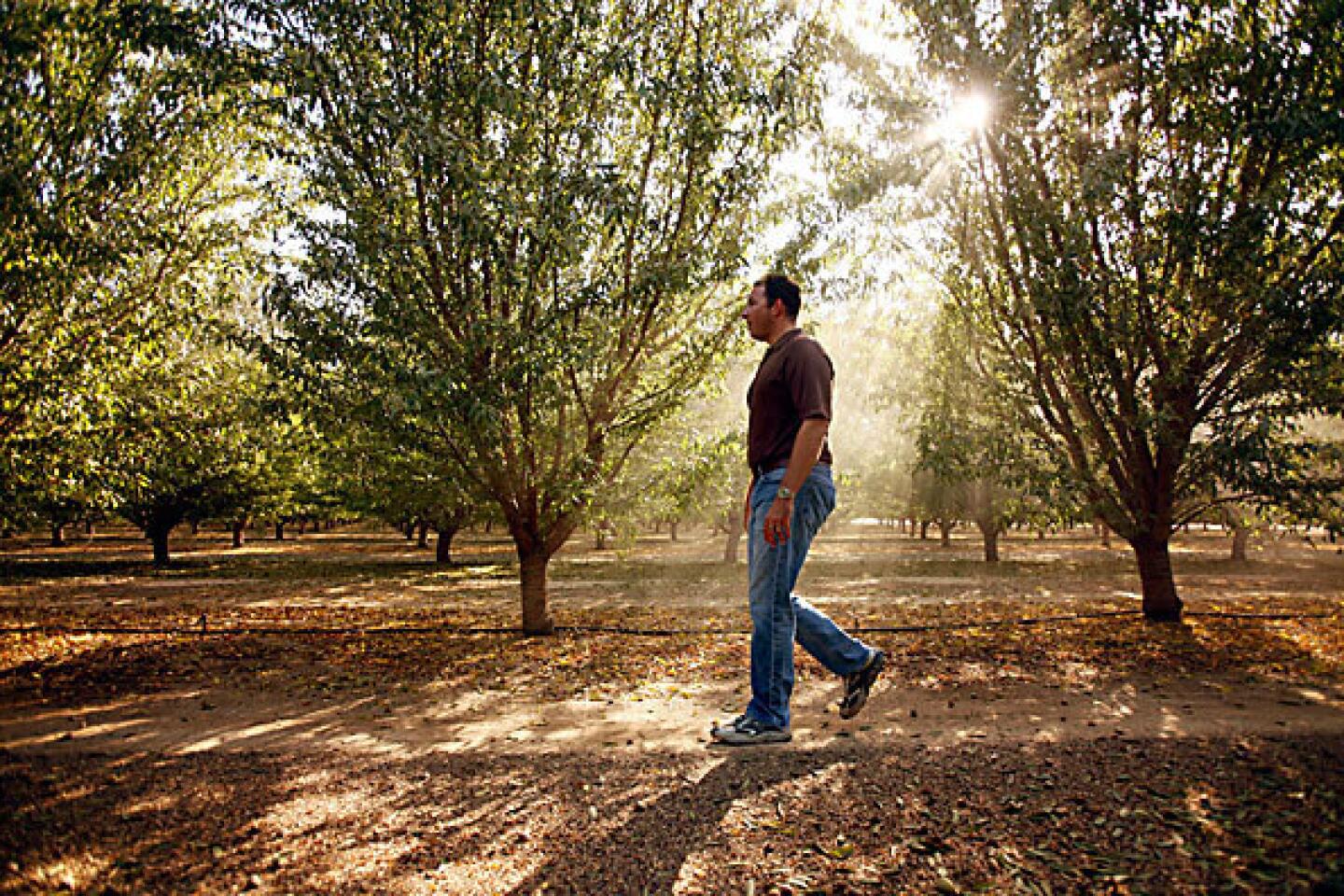

The ground trembles on Mike Young’s almond farm as the forklift-size yellow machine grabs a tree trunk and shakes it hard. Nuts rain like hailstones to the ground, where they’ll lie until another machine comes and sorts them.

Young once grew tomatoes, cucumbers and cotton. But in recent years, he’s shifted almost exclusively to nuts as worldwide demand has made the crop more profitable.

There’s another reason for abandoning row crops: Employees are a headache. Automation means Young no longer needs large crews of farmworkers to plant or harvest — and no more worrying about status, pay or benefits.

“Labor is so expensive,” said Young, whose great-grandfather started farming row crops in Kern County in 1910. “There’s their wages, truck, insurance, workers’ comp and the safety regulations. We went to a high-value crop that needed less labor input.”

Young estimates that at seasonal peaks, he now employs 70% fewer workers.

That sentiment isn’t unique to farming. Forced to cut costs during the recession, employers across the country are looking at ways to avoid hiring. They’ve accelerated use of computers and technology, replacing administrative assistants with software, cashiers with self-service kiosks and laborers with machines.

These structural changes mean some jobs that disappeared during the recession may never come back. Productivity gains are good for company profits and help the economy grow over the long run. But in the short term, the shift is exacerbating America’s jobless recovery.

“Recessions tend to act as ratchets; they’ll often speed the pace of fundamental changes that were going on in the economy anyway,” said Erica Groshen, vice president and director of regional affairs at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Ditching workers is an appealing prospect to many California farmers. Few states have minimum wages higher than California’s $8 an hour. The heightened focus on workers’ immigration status has increased farmers’ administrative burden.

With the help of machines, though, growers can continue to boost output while reducing headcount. Farm labor in California has fallen 11% over the last decade, yet cultivation of heavily automated crops soared over the same period: almond production has more than doubled, to 1.6 billion pounds.

“If cheap technology is available, you substitute technology for people,” said Allen Sinai, chief global economist at Decision Economics in Boston.

Automation has been a steady progression since the Industrial Revolution. Still, laying off workers is never easy. Recessions give companies a motive to move more swiftly than they otherwise might have to cut staff, outsource work to cheaper locations and implement labor-saving technology, Sinai said. When sales pick up, companies can help profits rise quickly by keeping a lid on hiring.

That’s part of the reason that earnings at some large companies have soared over the last year while job creation has lagged behind. In August, U.S. private sector employers added 67,000 jobs, far fewer than the 100,000 needed to keep pace with population growth.

Capital intensity — how much a firm relies on software, tools and machinery — contributed 1.6% to productivity gains from 2007 to 2008 after growing just 1% from 2000 to 2007, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Crisis is a catalyst for change. With their business hammered by 9/11, airlines cut labor costs by switching to computer kiosks to check in customers, said Greg Buzek, president of retail technology consulting firm IHL Group.

Other industries such as restaurants and retail stores are speeding adoption of these machines. About $300 billion worth of transactions moved through such kiosks in 2006. That figure is expect to be $455 billion this year and $700 billion by 2014, Buzek said.

EMN8, a San Diego company that provides self-service kiosks to restaurants including Jack in the Box, has seen a “dramatic increase” in interest from fast-food vendors in the last eight months, said Brent Christensen, vice president of sales at EMN8. The company leases the machines to restaurants, saving them big upfront costs.

EMN8’s machines look like colorful ATMs. Customers walk up to one, touch the screen, scroll through pictures of food, order and then swipe a card to pay. The company boasts that the machines can save restaurants 60% in labor costs.

“It is being driven by the opportunity to increase … sales without adding labor or food costs,” Christensen said.

Jack in the Box and other chains say their motive is to improve service, not reduce staff.

But data indicate that the recession accelerated the decline of jobs that are easily automated. Nationwide, employment in office and administrative support declined 8% from 2007 to 2009, after growing only 1% from 1999 to 2007, according to a report by David Autor for the Center for American Progress.

The decline is easily explained. Smart phones enable executives to handle communication when they’re out of the office. The Internet has made it easy for employees to book their own appointments and travel. In August, just over 20,000 people in California were employed by travel agencies and reservation services; that’s about half what it was a decade ago.

Janice Seaver worked as a reservations agent for a Laguna Hills time-share company for three years. But the 51-year-old said she can no longer find customer-service work because so much of it has been automated.

“They do it on their end because it looks good on paper, they’re not losing money,” she said. “But you lose all human contact.”

Economists said savings reaped from replacing employees such as Seaver with machines can be channeled elsewhere, leading to job creation in other sectors.

“In the short term, automation can create employment problems as we increase productivity but don’t have the income effects to circle back and create further demand,” said John Schmitt, a senior economist with the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “But it’s not going to be a problem in the medium or long term.”

Although the overall labor market may eventually bounce back, cities and regions that depended on jobs that are vanishing may not fare as well. Detroit, for example, is still grappling with the decline of its manufacturing base. Buttonwillow, the home to Young’s almond orchards, has watched its fortunes decline in the last 25 years.

Already, farm labor camps sit empty and decrepit. Boarded-up stores dot the streets of the once-bustling town, which once hosted 13 bars. Now there are none, said Rudy Ramay, who owns the Front Street Mini Mart. There are fewer laborers living in the town. Instead, they come through for a month or two and move on, since there are fewer seasons that they’re needed.

“This town used to be booming,” he said. “Now it’s dying.”