Ray Charles’ children battle over his legacy

Shortly before Christmas 2002, Ray Charles called a meeting of his 12 children at a hotel near Los Angeles International Airport. Ten of them, ranging in age from 16 to 50 -- with 10 mothers among them -- listened as their father told them he was mortally ill and outlined what they could expect from his fortune.

Most of Charles’ assets would be left to his charitable foundation. But $500,000 had been placed in trusts for each of the children to be paid out over the next five years, according to people at the meeting and a trust document.

Yet Charles’ description left so much to the imagination that some of the children came away with the impression that he meant to leave them $1 million each. Charles also hinted that there would be more for them “down the line,” which some interpreted to mean they would inherit the right to license his name and likeness for profit.

The confusion and contention that resulted from that family gathering, the only time so many of the children met with their father as a group, helps explain what has happened since. Charles exercised iron control over his music and recordings, but his legacy is in disarray, knotted up in legal disputes between the estate’s management and his family members, according to interviews, court documents and correspondence from the California attorney general’s office.

Born Ray Charles Robinson in rural Georgia in 1930, Charles died at 73 in Beverly Hills on June 10, 2004, after a long battle with cancer. In lawsuits filed against Charles’ former manager, several of his children have asserted that their father’s legacy has been mishandled by the manager and others associated with Ray Charles Enterprises, which holds the rights to his music, and the Ray Charles Foundation.

At issue are not only money and the family’s standing but also the fate of thousands of musical recordings, videotapes and other artifacts produced during Charles’ long career. Professional estimates place the value of Charles’ original masters at about $25 million -- on top of the $50 million he held in securities, real estate and other assets.

Charles’ children are hoping to win control of the marketing of their father’s name and image, and a greater voice in foundation affairs.

“No one is as committed to RC as his family,” said Mary Anne Den Bok, an attorney who is the mother of Charles’ youngest child, Corey Robinson Den Bok.

The foundation, which Charles originally established as the Robinson Foundation for Hearing Disorders, has come under the scrutiny of the California attorney general’s office, which at one point objected to its control by a single executive, without an independent board.

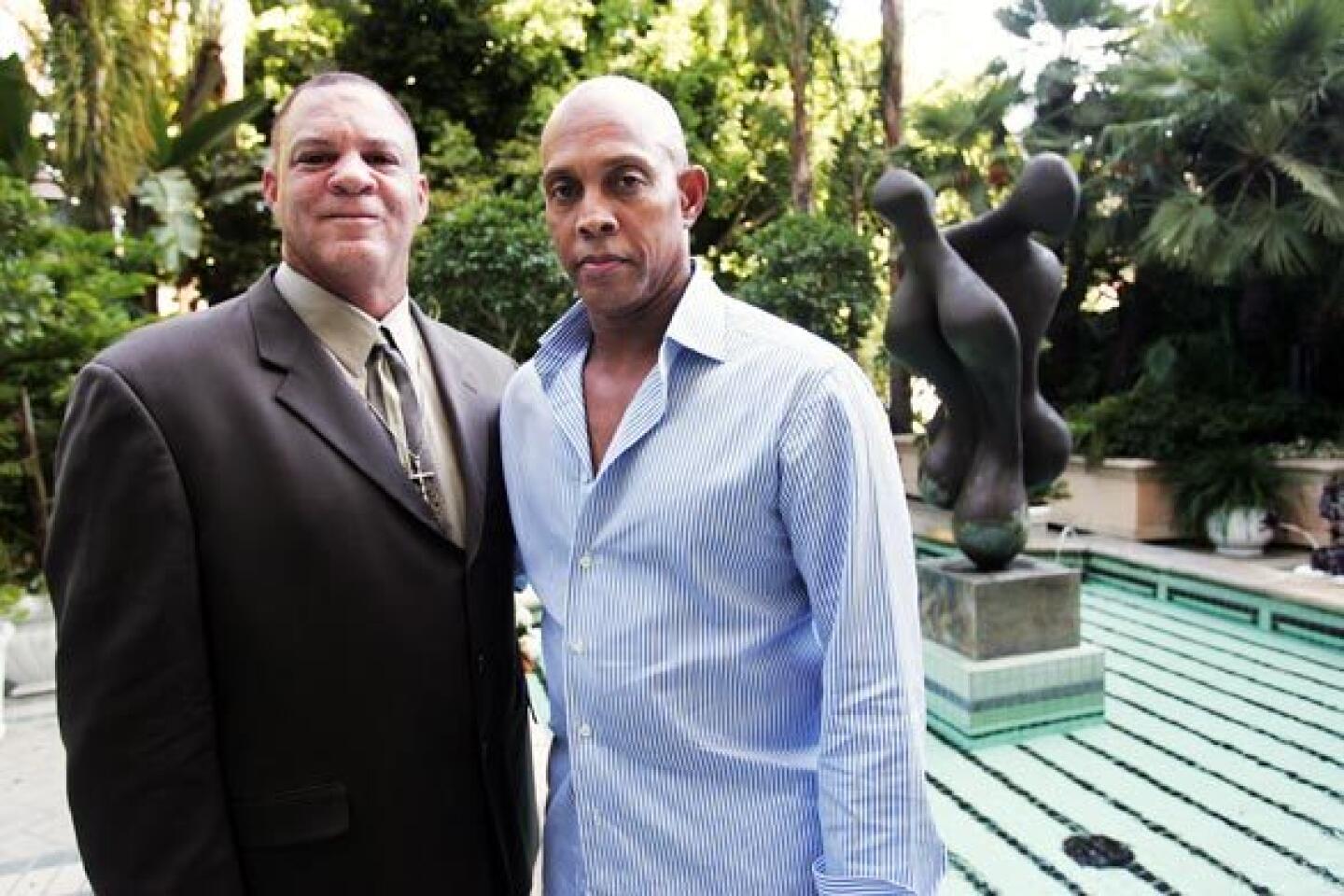

That executive, Joe Adams, is the target of the family’s complaints. Adams signed on as Charles’ manager in 1961. Toward the end of the artist’s life, Adams was perceived by Charles’ children and others close to him as controlling access to the star.

After Charles’ death, Adams ended up with virtually unchallenged power over the estate. He was head of Ray Charles Enterprises, director of the foundation and trustee of the children’s trusts. In some cases, co-officers appointed by Charles departed their roles while Adams remained.

Family members contend that Adams’ leadership has tarnished the image of the artist, who was known for decades as the “Genius” -- a title bestowed on him by Frank Sinatra. Adams’ actions, along with those of other executives of the estate, have “distorted and trivialized” the value of the Charles name, alleges a federal lawsuit that Den Bok filed in the name of her son and nine of his siblings.

Adams, 86, declined requests for an interview. However, Jerry Digney, his spokesman, called the assertions “old, baseless allegations.”

The family blames Adams for the release of two posthumous Ray Charles CDs that, in a departure from Charles’ usual practice, were remixed from work he left behind and overdubbed with tracks by other singers. Both were commercial disappointments, even though they were released after the 2004 Oscar-winning biopic “Ray” had increased interest in Charles’ music.

The children have been unable to obtain an accounting of the estate, in part because their legal right to the information is murky.

Adams has kept the children and other family members from participating in ceremonies honoring their father, they say, even his funeral.

Adams interrupted a private family service at the Angelus Funeral Home in Los Angeles, attempted to eject some of the participants and ordered the casket removed from the chapel, according to several people who were there.

“The biggest issue with me is disrespect for the family and kids,” the Rev. Robert Robinson, one of Charles’ sons, said in an interview. “If you respect a man and his work, then you respect his kids. His blood is flowing through our veins.”

Charles’ 12 children are widely dispersed. Six call California home, and one lives abroad. Four are especially involved in controversies over the estate: Robert, 46; Ray Charles Jr., 52, whose mother, Della Robinson, was married to Charles from 1955 to 1977; Raenee Robinson, 46, who is currently fighting a lawsuit filed by Adams over her right to market items bearing her father’s image; and Corey, 20.

Trust documents and the only known copy of Charles’ will are silent on the rights to his image, although his children contend that he pledged these benefits to them.

“My father told me, ‘You have my name and you’ll be able to use it,’ ” said Ray Jr., his eldest son.

In 1992, Charles set up a partnership with Ray Jr. and his second daughter, Raenee, to market T-shirts and other items bearing Charles’ image. “I wanted to give my kids something of their own,” he said in a 2004 deposition related to a licensing dispute.

But Ray Jr. maintains that virtually every time he has proposed a Charles-branded venture, it has been blocked by Adams. He contends that in 2005, when he sought a payout from his trust to enter a drug rehabilitation program, Adams forced him to sign over his interest in the marketing partnership first.

Ray Jr. is suing Adams to rescind the share transfer, which he says occurred under duress and which apparently gave Adams 60% control of the partnership. Adams has not formally responded to the allegations

After their father’s death, Robert Robinson and other family members complained to then-state Atty. Gen. Bill Lockyer about their exclusion from the foundation. But Lockyer’s staff told them they had too little documentation to make a case. “They said they don’t see a paper trail,” Robinson said.

In the federal lawsuit filed against Adams and other executives, Mary Anne Den Bok alleges that Adams was paid nearly $1.2 million in “improper compensation” in 2005 and 2006 and that some of Charles’ master recordings may have been sold, an action people close to the artist say would directly contradict his wishes.

Adams has not filed an answer to the complaint, according to court records.

In February 2006, Adams’ stewardship of the foundation was questioned by Deputy Atty. Gen. Wendi A. Horwitz. After learning that Adams was serving simultaneously as chairman, president and treasurer of the foundation -- in violation of state law -- she gave Adams 30 days to comply. He appointed a new treasurer and a few months later added a majority of independent outsiders to the board.

The attorney general’s office never took public action against the foundation. In December, Adams resigned as president of the foundation and of Ray Charles Enterprises. He was succeeded by Ivan Hoffman, a lawyer who had worked with the estate. However, a receptionist at Ray Charles Enterprises said last week that Hoffman was not currently its president. Hoffman and a company spokesman declined to comment.

Adams still exercises power at the organizations, the lawsuit filed by Den Bok alleges. It is unclear whether he still holds any formal titles. A spokesman for Atty. Gen. Jerry Brown, who succeeded Lockyer in 2006, had no comment.

In 1997, Charles decided he needed a fresh approach to his career and attempted to replace Adams with Jean-Pierre Grosz, a 50-year-old French artists manager who had become a close friend. Charles, however, apologetically sent Grosz home to Paris after Adams refused to relinquish his office in Charles’ Washington Boulevard studio, according to the French manager.

Charles soon found another job for Grosz: safeguarding his musical legacy. Charles believed preservation of his recordings “was a No. 1 priority,” Grosz said in an interview from Paris. “He told me, ‘I want you to do that,’ ” Grosz recalled.

Grosz said Charles assigned him to assemble and catalog all videos and audiotapes of his performances and remaster -- or restore -- any originals that had deteriorated. He was to be paid $2,000 a week plus fees for any albums he produced.

About three months after Charles’ death, however, Grosz received a document in which Charles purportedly “instructed” Adams to pay him only $2,000 a month for no more than three years. The document had been signed by the artist, according to a cover letter to Grosz from Charles’ estate lawyer examined by The Times.

Grosz said the document bore what looked to him like a forged signature. Adams later acknowledged in a court filing in an unrelated lawsuit that he had signed the document in Charles’ name under a power of attorney that Charles had granted.

After Grosz was moved aside, Ray Charles Enterprises released two albums that Grosz and other Charles associates say the artist never would have approved.

The first, “Genius & Friends,” released in 2005, was a compilation of duets designed as a sequel to the hit “Genius Loves Company,” the final album released in Charles’ lifetime. But unlike that CD, the duets on “Genius & Friends” were taken from old Charles masters, with the voices of his collaborators dubbed in.

The costars included several artists with whom Charles had never recorded and one, Patti LaBelle, whose style he disliked, according to Grosz and family members. A recording of John Lennon’s “Imagine” that Grosz had produced for Charles was overlaid with vocals by Ruben Studdard, an “American Idol” winner.

The second album, “Ray Charles Sings, Basie Swings,” released in 2006, is a remix using unreleased Charles masters with the orchestral tracks replaced by arrangements by a band that records under the name Count Basie. The original Count Basie died in 1984, two decades before the new tracks were recorded.

The tracking service Nielsen SoundScan says “Genius & Friends” sold 161,000 copies and the Basie remix 209,000. “Genius Loves Company” has sold 3.2 million copies.

Family members say their right to a voice may become more tenuous with time, given Adams’ advanced age. “After Joe passes, who knows?” said Ray Charles Jr. “He can give it to anyone he wants.”