Bill offers a path for sexual harassment victims silenced by their employers

New legislation proposed Wednesday would prevent companies from keeping employees’ sexual harassment complaints in private arbitration, where accusations are kept confidential and companies can influence who adjudicates the case.

The bipartisan bill would allow victims of sexual harassment or gender discrimination in the workplace to take their claims to court instead.

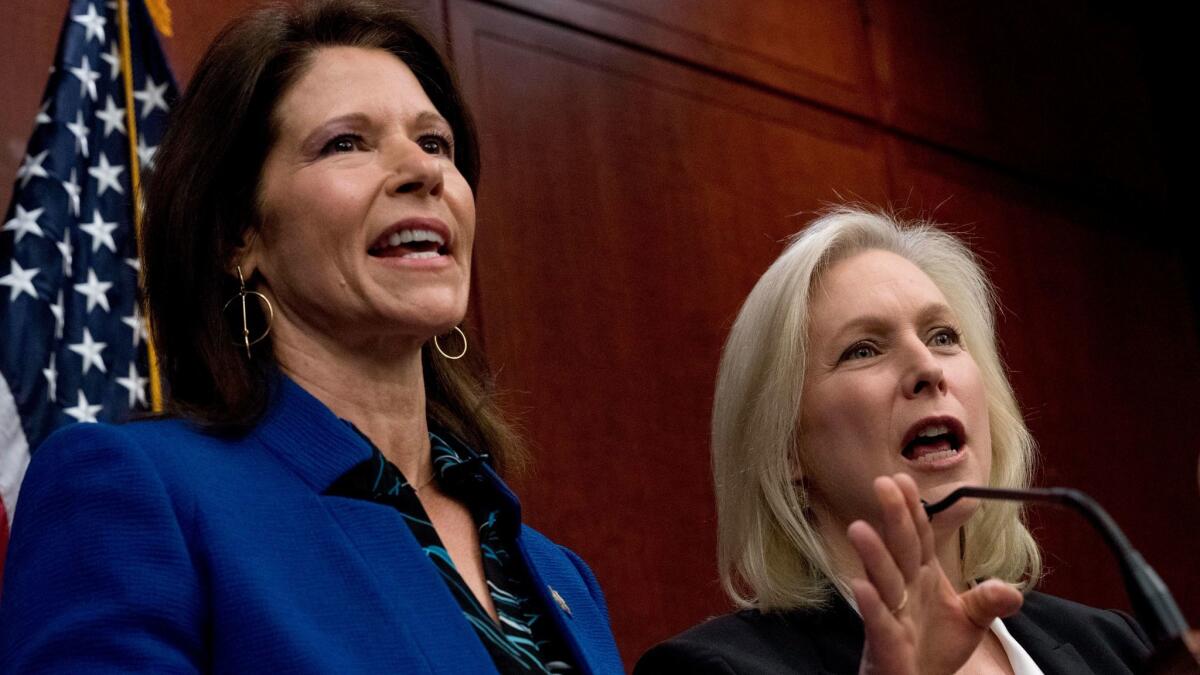

“If you have been subjected to sexual harassment or discrimination in the workplace, we think you, not the employer, should have the right to choose to go to court,” said Rep. Cheri Bustos (D-Ill.), who introduced the bill. “No more telling women they have to put up with harassment and stay silent any longer.”

In a year of broken silence about sexual harassment, the bill offered a reminder that accusers’ quest for resolution is often complicated or kept out of reach by legal restrictions beyond their control. Forced-arbitration agreements have been repeatedly cited this year as a barrier for women seeking to name perpetrators of sexual misconduct.

Bustos said that she was inspired to pursue the legislation by a class-action case involving Signet Jewelers, the parent company of Jared the Galleria of Jewelry, Kay Jewelers and Sterling Jewelers, whose workers must sign forced-arbitration agreements as a condition of their employment.

Roughly 250 former Sterling employees filed sworn statements as part of a class-action arbitration case alleging that female workers in the late 1990s and 2000s were routinely groped, underpaid and pressured to cater to their bosses’ sexual demands in order to stay employed. Sterling has disputed the allegations.

Fear and panic in the HR department as sexual harassment allegations multiply »

The arbitration was first filed in 2008 by more than a dozen women who accused the company of widespread gender discrimination. The class-action case is still unresolved and now includes 69,000 women who are current and former employees of the company, which operates about 1,500 stores across the United States. One of the original women who brought the case, lawyers involved in the hearing said, died in 2014 as proceedings dragged on without resolution.

Heather Ballou, a class member in the lawsuit and a former Kay employee who said she was pressured into having sex with a district manager promising to help her transfer to a better store, said she was encouraged by the legislation and hoped that it would make it easier for women to break their silence.

“That’s the whole reason I didn’t come forward and a lot of women haven’t come forward,” Ballou said in an interview. “You go to arbitration, and it’s a black hole of nothing. Why would anyone do that when, in the process of that, you are getting fired, you’re ruining your reputation, you’re getting blackballed by the industry, you’re ruining your life — and nothing comes of it?”

Hundreds allege sex harassment, discrimination at Kay and Jared jewelry company »

David Bouffard, Signet’s vice president of corporate affairs, said in a statement: “We are currently reviewing the legislation and therefore cannot comment further on any specifics. Signet is committed to maintaining a safe and inclusive workplace, and we remain confident that the systems and practices in place for filing grievances are fully compliant with legal requirements.”

A trial in the private arbitration is scheduled for next year.

Ballou, who left the company in 2009 and is studying to become a nurse, said it has been difficult to watch the recent months of high-profile sexual-harassment cases, sparked by numerous women accusing movie producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual misconduct.

While perpetrators in several cases were exposed and quickly vilified, she feels frustrated by the arbitration’s private proceedings and long-running limits on her ability to speak openly about the case.

“It felt empowering on one hand that we aren’t the only ones, but it scares me a little bit. All of these celebrities have come out, and it makes me feel like the little people like me are going to get tossed aside,” Ballou said.

“I didn’t have Harvey Weinstein,” she added, “but I had my district manager, people in power above me, do those things to me.”

Gretchen Carlson, a former Fox News anchor who accused the network’s late chairman Roger Ailes of punishing her for rejecting his sexual demands, was prevented by an arbitration agreement from suing the company. Instead, she sued Ailes directly and received a $20-million settlement.

Carlson, speaking alongside lawmakers at the Capitol Hill news conference Wednesday, called forced arbitration “un-American” and a “harasser’s best friend.”

A growing number of U.S. companies require new workers to sign employment agreements forcing them to resolve disputes through arbitration, a private legal system in which companies often have the upper hand, labor advocates say.

About 56% of private-sector nonunion employees, or more than 60 million workers, are subject to forced-arbitration agreements, according to research from the Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank.

Lawyers and labor advocates say companies use the agreements as a way to prevent workers from joining together in legal action or discussing their cases publicly. Companies and arbitration associations say the private legal system provides a quicker and more efficient way to resolve employee disputes.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), a co-sponsor of the bill, said he hoped that the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Business Roundtable and other business-community leaders would speak out against forced-arbitration clauses, which he said provided companies an unfair advantage over employees. “It may be good business” now, Graham said, but “we’re going to make it bad business.”

A Chamber of Commerce representative said: “While no senator has yet reached out to the Chamber about this legislation, we will review it carefully. The Chamber will work with anyone to make sure appropriate steps are taken to combat sexual harassment.”

A Business Roundtable spokeswoman said the group is “analyzing the legislation closely” and “agrees that workplaces should be free from harassment of any kind.”

Harwell writes for the Washington Post.