Road to S&P settlement began with Jerry Brown chat, novel legal strategy

Two Justice Department lawyers leading an effort to hold financial firms accountable for the mortgage-fed debacle that fueled the Great Recession stopped in to talk strategy in mid-2009 with Jerry Brown, then California’s attorney general.

“What are we going to do about the ratings agencies? What about them?” Brown asked the pair, Tony West and Geoffrey Graber.

“And when Jerry Brown left the room,” Graber recalled later, “Tony looked at me and said, ‘I really want to look at the ratings agencies.’”

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

S&P settlement: In the Feb. 4 Section A, an article about a settlement with Standard & Poor’s Financial Services identified a failed San Dimas financial institution as Western Federal Credit Union. The full name was Western Corporate Federal Credit Union.

------------

That conversation led to an unusual legal strategy and, ultimately, to the first civil lawsuit blaming a major ratings company for contributing to the 2008 financial crisis and exacerbating the recession.

On Tuesday, the work came to fruition with a record settlement of nearly $1.4 billion with Standard & Poor’s Financial Services over allegations that the world’s largest ratings company misled investors with overly rosy ratings on securities backed by some of the riskiest subprime mortgages and other assets created in the housing boom.

The agreement with S&P and its parent company, McGraw Hill Financial Inc., ends nearly two years of harsh litigation pitting S&P against the Justice Department, California and 18 other states.

S&P held itself out as an independent and objective “gatekeeper in the world of sophisticated finance,” Stuart F. Delery, acting associate attorney general, said at a news conference. Instead, the government alleged, S&P manipulated its ratings standards and analyses to preserve market share and profits.

“S&P issued inflated ratings on billions of dollars’ worth of securities despite knowing that the quality of the underlying assets was impaired and that the ratings would not hold,” Delery said. “Put simply: We brought this case because S&P committed fraud.”

S&P denied committing fraud, saying it settled to “avoid the delay, uncertainty, inconvenience and expense of further litigation.”

California will receive $210 million, the most of any state, and will use most of it to help offset losses that the California Public Employees’ Retirement System and California State Teachers’ Retirement System — the nation’s two largest public pension funds — sustained on mortgage-related securities after relying on allegedly faulty S&P ratings.

Separately, S&P agreed to pay CalPERS an additional $125 million to settle the fund’s claims over allegedly defective ratings on three mortgage securities.

“California’s public pension funds suffered significant losses due to S&P’s failure to honestly and accurately disclose the risk of the very investments that caused an international economic recession,” California Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris said.

Some observers criticized the overall settlement as too light.

“Ironically, the claims being made about the settlement appear to be as inflated as the credit ratings were in the years before the financial crash,” said Dennis Kelleher, chief executive of Better Markets Inc., a Washington financial reform group. “Allowing S&P to eliminate its liability merely by using shareholders’ money to pay a settlement, however big, seven years after the crash is not a meaningful punishment.”

Still, authorities said, the lawsuit became the model that helped the government win settlements with major banks — $7 billion with Citigroup Inc., $13 billion with JPMorgan Chase & Co. and $19 billion with Bank of America Corp. Like S&P, they were accused of understating the risks of subprime mortgage investments.

California became fertile ground for lending lawsuits mainly because it was home to the biggest subprime mortgage lenders — names such as Countrywide Financial in Calabasas and Ameriquest, New Century and Option One in Orange County. They were major sources of the risky home loans precipitating the mortgage meltdown of 2007 and the global economic crash.

Federal and state authorities, pressured by lawmakers and the public in general, launched civil and criminal investigations of mortgage lenders, Wall Street banking firms and even home builders, looking for evidence that books were juggled to conceal loan problems while executives collected large salaries.

In the end, the government drew fire from critics for declining to press criminal charges against any Wall Street executives or mortgage leaders such as Countrywide co-founder Angelo Mozilo, whose $73-million settlement of civil fraud charges was paid mostly by insurance and the company’s acquirer, Bank of America.

In 2009 amid the government’s efforts, Graber, a USC law school graduate working at a San Francisco firm, was recruited by former colleague West, then head of the Justice Department’s civil division, to help lead federal and state efforts to wrench civil penalties from firms involved in issuing the faulty mortgage-backed securities.

In an interview last year, Graber said he embraced the role after seeing firsthand the damage that mortgage defaults and foreclosures had brought to California, among the states hardest hit by the crisis.

“It wasn’t theoretical,” he said. “I had family and friends who lived in devastated neighborhoods, who knew people who lost their homes.”

Graber and West crisscrossed the country in mid-2009, conducting strategy sessions with U.S. attorneys and state officials and talking about pursuing large banks, loan brokers, appraisers and other participants in the mortgage business.

“And right in the center were the ratings agencies, and S&P was the largest,” Graber said.

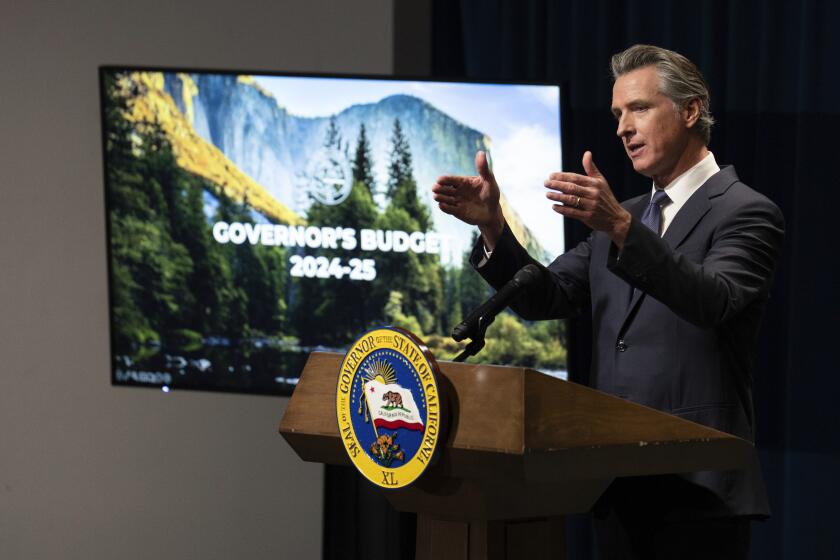

At the instigation of Jerry Brown, now California’s governor, Graber said, he and West began taking a harder look at ratings firms.

Through his press secretary, Evan Westrup, Brown said he raised the issue in “a number of other conversations” at the time. “We were taking every step we could to hold Wall Street accountable, and that certainly applied to the rating agencies,” he said.

Graber said a light went on soon after he talked to Leon “Lee” Weidman, chief of the civil division at the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles.

Weidman was known in Washington for using the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989 to pursue smaller mortgage offenders — “people who had lied on loan applications, that sort of thing,” Graber said.

That law was aimed at those whose speculative investments and outright fraud caused the failure of more than 1,000 savings and loans, the largest of which were in Southern California. It imposes vast financial penalties for causing losses at government-insured banks and enables criminal allegations — wire fraud, mail fraud and bank fraud — to be filed as civil cases with a lower standard of proof.

“I said, ‘Look, Lee … we’ve got another idea about using FIRREA. It’s a little bit different. Then I walked him through the plan,” Graber said. “There was dead silence for about 10 seconds. And then Lee said, ‘Wow. That sounds really interesting.’ Because at the time no one had used it in the way we were proposing to use it.”

To pursue their case, prosecutors needed specific victims. One was readily at hand: Western Corporate Federal Credit Union in San Dimas. It was seized by federal regulators in March 2009 after losing nearly $7 billion, largely on mortgage-backed bonds that failed despite top credit ratings from S&P.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Feb. 4, 12:20 p.m.: An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified Western Corporate Federal Credit Union as Western Federal Credit Union.

------------

An example was a $100-million investment in a complex mortgage deal called Sorin CDO VI Ltd., to which S&P had assigned its highest rating, AAA. Sorin’s default in 2008 left Western with a loss of $90 million, the lawsuit said.

The FIRREA-oriented investigation of S&P, initiated in November 2009, was not filed until February 2012, reflecting the complexity of the case and failed attempts to negotiate a pre-lawsuit settlement.

The Justice Department’s Delery lauded federal prosecutors in Southern California and in the civil division. He suggested that more FIRREA suits were in the works but wouldn’t confirm reports that Moody’s Investor Services, S&P’s top rival, was next in line.

Reckard reported from Los Angeles and Starkman from New York.