She earns more, and that’s OK

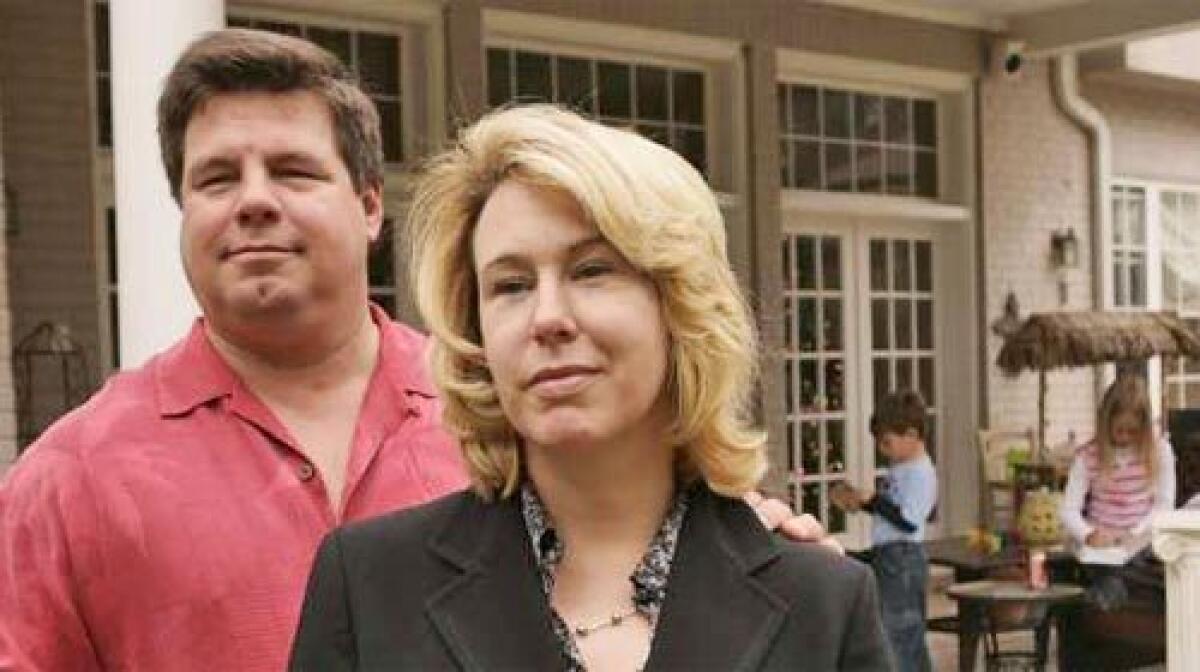

Aaron Frazier married his college sweetheart Danielle four years ago knowing that she out-earned him by $10,000 a year. Now, that gap is even bigger.

But even though Aaron’s accountant salary today is half the $90,000 his wife makes monitoring clinical drug trials, it still doesn’t cause any friction.

“I think both of us are pretty modern,” said Danielle, 29, of Antioch, Tenn.

“She does more cooking, and I do more housework,” said Aaron, 30, adding that if they had a baby, he would start out being the primary child-care giver.

Couples such as the Fraziers -- with the wife bringing home most of the bacon -- are becoming increasingly common and accepted among the nation’s twenty- and thirtysomethings, the result of shifting education and job market patterns, and new attitudes toward work, family and gender differences.

That could help accelerate the growth in the number of marriages in which women are the sole or primary breadwinners. Census Bureau data show that 25.3% of women in two-income marriages bring home the bigger paycheck, up from 17.8% in 1987.

Younger women, now graduating from college at higher rates than men and aggressively recruited by many employers, are becoming anything but desperate housewives. Some, like Danielle Frazier, out-earn male peers starting with their first jobs.

The salaries of college-educated women have risen much faster than those of male graduates, up 34.4% since 1979 versus 21.7% for men, according to Catalyst, a New York-based research group.

Among twenty- and thirtysomethings, more women than men have college degrees. The gap is widest among 25- to 29-year-olds, according to the Census Bureau, with 25.5% of men holding a bachelor’s degree as compared with 32.2% of women. Women now account for close to half of medical and law students, funneling them into lucrative careers.

The Labor Department projects the education disparity will widen in coming years.

Partly fueling that gap is the belief among many women that they still need to be better trained than men to succeed -- “to jump through the hoops,” said Stephanie Coontz, a historian at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, Wash. “Men don’t feel that as much.”

Indeed, men in their 20s and 30s are increasingly comfortable with being the lower-paid spouse and more willing than their fathers -- eager, even -- to take on responsibility for child rearing and household duties, surveys show.

Although men overwhelmingly say they would prefer to work, a growing number have told pollsters over the last 20 years that they’d be OK with their wives supporting them.

The most recent Gallup Poll, taken in 2005, found the strongest support for that view, 27%. And because that trend is most pronounced for men younger than 50 -- at 35% -- even more men may opt to become the family caretaker.

“Men are saying, ‘I don’t mind being married to a woman who earns more than I,’ and women are giving up the notion that they have to find a man who can support them,” said Coontz, who has written several books on marriage and gender roles.

To be sure, men overall still define their self-worth in terms of their salaries more than women do. And men on average continue to bring home bigger paychecks.

But the pay gap is shrinking, even as some highly paid women have chosen to leave their jobs to raise children and others run into glass ceilings. Women earned 81 cents for every dollar a man made in 2005, up from 76.1 cents in 2001 and 66.6 cents in 1983, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The agency found the gap narrowest for workers in their 20s and early 30s. Women 25 to 34, for example, earned 89 cents for every dollar men made in 2005, whereas among 35- to 44-year-olds, women pulled in 75 cents for every dollar that men made.

Many female baby boomers have out-earned their husbands for years, the result of early professional choices and ambition. Others revved up stalled careers in their 40s and 50s when their children left home or as their husbands began to downshift professionally or were laid off or retired.

No matter their age, women say their fatter paychecks reflect their soaring career goals, loose them from traditional roles as wives or mothers, and give them a stronger voice in their marriage. “I don’t feel beholden to my husband,” as one woman put it.

Take Kathryn Nieland. Now the managing partner of accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers’ New Orleans office, Nieland earned roughly the same as her engineer husband, Chris, when they began their careers. But by 2002, after 11 years of marriage, her paycheck had grown so much faster than his that the couple decided he would stay home with their two young children.

Chris now sells real estate part time but remains the family’s main homework minder, school volunteer and afternoon chauffeur.

“The choice we made has made us as a family so much happier,” Kathryn said.

The 39-year-old’s ebullience is hardly unique.

“There’s a certain exhilaration that women are feeling,” historian Coontz said.

“Women have suddenly been freed to pursue ambitions that they once had to channel into finding a successful man rather than being a successful person,” she said.

Wives also are reporting that their husbands roll up their sleeves at home more often, doing dishes and laundry and caring for the children -- 34% as compared with 24% a decade ago, according to Ellen Galinsky, president of the New York-based Families and Work Institute.

Matt Cohen, 35, is one such happy homemaker. An Irvine freelance website designer, he earns about half what his wife, Heidi, 36, makes as a rabbi with a six-day workweek. He works from home around the schedules of their two young children and heads the Orange County Dads, a support group for at-home and work-at-home fathers.

“I’ve always wanted to do this,” he said of his role as primary child-care giver. “My mom stayed home and my dad was always there at night. We had a great growing-up and I wanted to provide that for my kids.”

Younger couples increasingly expect this sort of equality or flexibility, Coontz said. Women who first poured into the workforce during the 1970s sparked this attitudinal change, she said.

They and the growing number of women who followed them into offices and factories during the 1980s and 1990s “created a whole new climate,” Coontz said.

Chris Nieland’s willingness to handle domestic affairs helped tremendously when his family lost their home to Hurricane Katrina.

The couple since have moved eight times, with Chris handling the logistics.

They couldn’t have managed, Kathryn said, if Chris had to worry about making money as well.

She said her husband was “always very supportive of my career and happy when I got good raises.”

Still, Kathryn recalled, “we weren’t perfect at this right away. It took us some time to realize that we could do things differently.”

For other couples, however, the paycheck gap becomes a sore point.

Personal-finance expert Suze Orman said the issue generated a huge share of the advice requests women sent her. Because “money is a physical manifestation of who you are,” she said, some men who earn less than their wives or girlfriends feel they must be less valuable people, and that belief can put a strain on relationships.

Some marriages don’t survive. Steven Nock, a University of Virginia sociologist, found that women who earned more than their husbands were more likely than higher-earning men to leave an unsatisfying marriage.

Ego-deflating jokes or remarks at wives’ office parties sometimes grate at lesserearning husbands.

Parents and in-laws can inadvertently make matters worse.

Aaron Frazier said that when Danielle had gotten a raise, his mother was happy for her, but “she’s pushing me to step up and get my income increased.”

He is pushing himself as well, planning to eventually get a master’s degree with the goal of a management job.

“I think at some point the [salary] gap will close,” Aaron said.

molly.selvin@latimes.com