When historic preservationists and homeowners can’t be neighborly

Los Angeles’ reputation for razing historic buildings with near gleeful abandon has long faded. The city now has the second-largest historic-designation program in the country, bested only by New York.

Along with that standing comes unavoidable bureaucracy as the city deems what changes are permitted within historic homes. But those layered processes, while safeguarding the city’s past, can create a disconnect between two worlds: the lofty realm of preservationists and the everyday concerns of ordinary homeowners.

“The language and process has become so caustic,” said Leo Marmol, of the Los Angeles-based design-build firm Marmol Radziner. “The preservation community has to get off its high horse and speak in a human way.”

Preservationists might be the first to admit their specialized field can appear exalted, and that battles to save historic properties can be both political and brutal.

Crusades over what may or may not be done with homes “can be exhausting, awkward, uncomfortable,” said Adrian Scott Fine, director of advocacy at the L.A. Conservancy. He also admitted that preservationists “speak in code sometimes, such as the different levels of historic designations. It can be off-putting and sound scary.”

A prime illustration of that misunderstood jargon — and the divide between preservationists and homeowners — was the battle over 4221 Agnes Ave. in Studio City.

The residence is among five 1937-1938 American Colonial Revival homes, three of which were built by architectural designers Arthur and Nina Zwebell. The grouping is listed as the “Agnes Avenue Residential Historic District” on the city’s historic inventory, SurveyLA.

However, that designation offers no protection for the homes. It merely means the city identifies the properties as being eligible for landmark status, to join the roster of L.A.’s more than 1,000 historic-cultural monuments. But homeowners easily confuse the historic districts with “historic preservation overlay zones,” a much stricter neighborhood designation, one that prohibits untoward alteration and demolition of a group of homes.

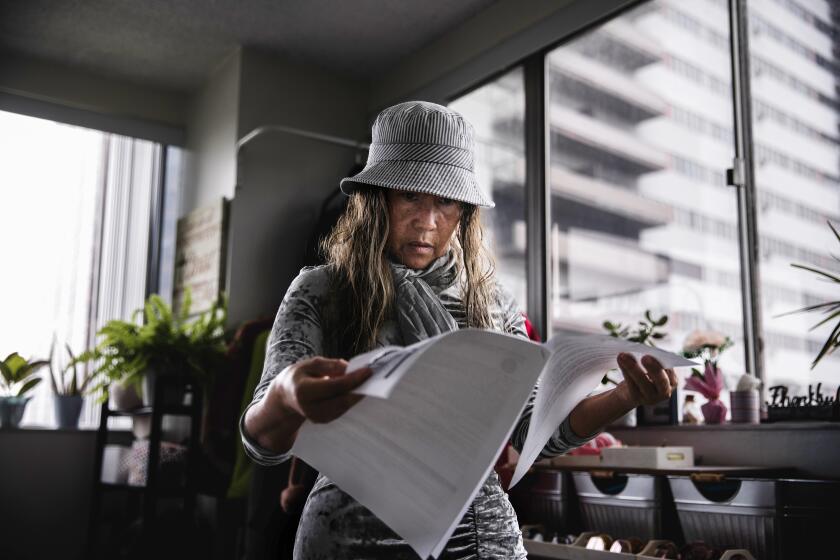

Daveena Limonick, who owns one of the Agnes Avenue homes, assumed yet something else: that the five properties were already protected as landmarks, simply because they belonged to a “historic district.”

Properties become historic-cultural monuments only after a public hearing and City Council vote, and then they’re shielded from undue alteration with stays of demolition, similar to properties within historic preservation overlay zones. Until then, they lack any special protection, even as part of a “residential historic district.”

Enter Kevin Schoeler, 56, a nonprofit consultant and philanthropic advisor who, with his partner in 2017, bought the home next to Limonick’s: 4221 Agnes Ave. Schoeler first confirmed with city planning that it was free from restrictions on modifications or demolition, even with its official-sounding “historic” moniker.

In January 2018, after concluding that a renovation would not be cost-effective, Schoeler applied for a demolition permit to clear the way for a new residence.

That same month, upon hearing the news and realizing the houses were not protected, Limonick submitted a landmark nomination for Schoeler’s home. In an interview later, she suggested he was a developer looking for tear-downs.

Told of her allegation, an incredulous Schoeler responded, “Wow! I’ve never built a house in my entire life, nor has anyone built one for me. I’m a private individual. We were building a house for our family.”

Misinformation and heated accusations can further snarl the disconnect between preservationists and others, who — while appreciating history — are not convinced that landmarking is appropriate for certain properties.

Schoeler had a say on his home’s fate during a March 2018 public hearing wherein the Cultural Heritage Commission deemed the property an “excellent example of American Colonial Revival” architecture and a “notable work of a master builder.”

Schoeler argued that his home was a poor example of such architecture, given that the Zwebells took considerable liberties with the style — for example, instead of a Colonial’s symmetrical facade, the home has three roof lines.

He relayed that Arthur Zwebell was not known for Period Revival work, or even single-family homes, but rather 1920s Spanish- and Andalusian-influenced courtyard apartments; several of those are landmarked.

Cultural Heritage Commission President Richard Barron was not available for comment on the dispute.

Schoeler’s property was declared a historic-cultural monument after a May vote by the City Council.

Schoeler said he felt ambushed at the hearing, defending his property against both the city’s will and “dozens of people who live on the street.”

“In the end, you’re fighting City Hall, which is a losing proposition,” he said.

Schoeler sold the home in December 2018, taking a $148,000 loss as well as wasting $75,000 on unused design-build plans and city permits and fees.

As a result of the battle, owners of the other two Zwebell houses are proceeding to have their properties designated landmarks, Limonick said.

Architect Leo Marmol declined to weigh in on the merits of the landmarking, but he said that “just because a structure is old does not make that structure significant.”

“Preservation is not about stopping change; it’s about managing change,” he said.

The saying is also favored by preservationists. Exactly what that change looks like will no doubt always be up for debate.