What were they thinking?

Urban sprawl is an L.A. concept. We should’ve trademarked it. Supersized housing? Ditto. Forget the scant skylines of downtown, Century City and the few pockets of verticality scattered about, the architecture of Los Angeles lies low and long.

An expansive connection to the earth is our birthright, and when the frontier mentality and the can-do spirit become one, the results can be magnificent. But when they collide — watch out. The results are eyesores, so out of all proportion that only we can call them our own.

The Monster Garage

Los Angeles architecture has always loved cars. Arts and Crafts buildings employ porte-cocheres. Master architects such as Wallace Neff designed elaborate motor courts. So it probably shouldn’t surprise us that circular driveways soon became a status symbol. Not too far in our past, even the smallest residential lot had a concrete arc carved out. But would that be enough?Not quite. Bored with mere breezeways that connected detached garages to houses, homeowners sought to bridge the distance with direct access to kitchens, laundry centers and dens. Garages doubled, even tripled in size to accommodate second pantries, wood shops and sports lockers. Often these structures jutted toward the street, creating what is euphemistically called a “snout house” and throwing off any respectable sense of symmetry — unless you bought out the neighbors and added on a wing.

Today wider “sweep” drives lead to car hangars that often have the architectural detailing (cornices and oculus windows, anyone?) and the square footage of a small home (with second stories dedicated to playrooms or media centers).

No wonder they’re called Garage Mahals.

*

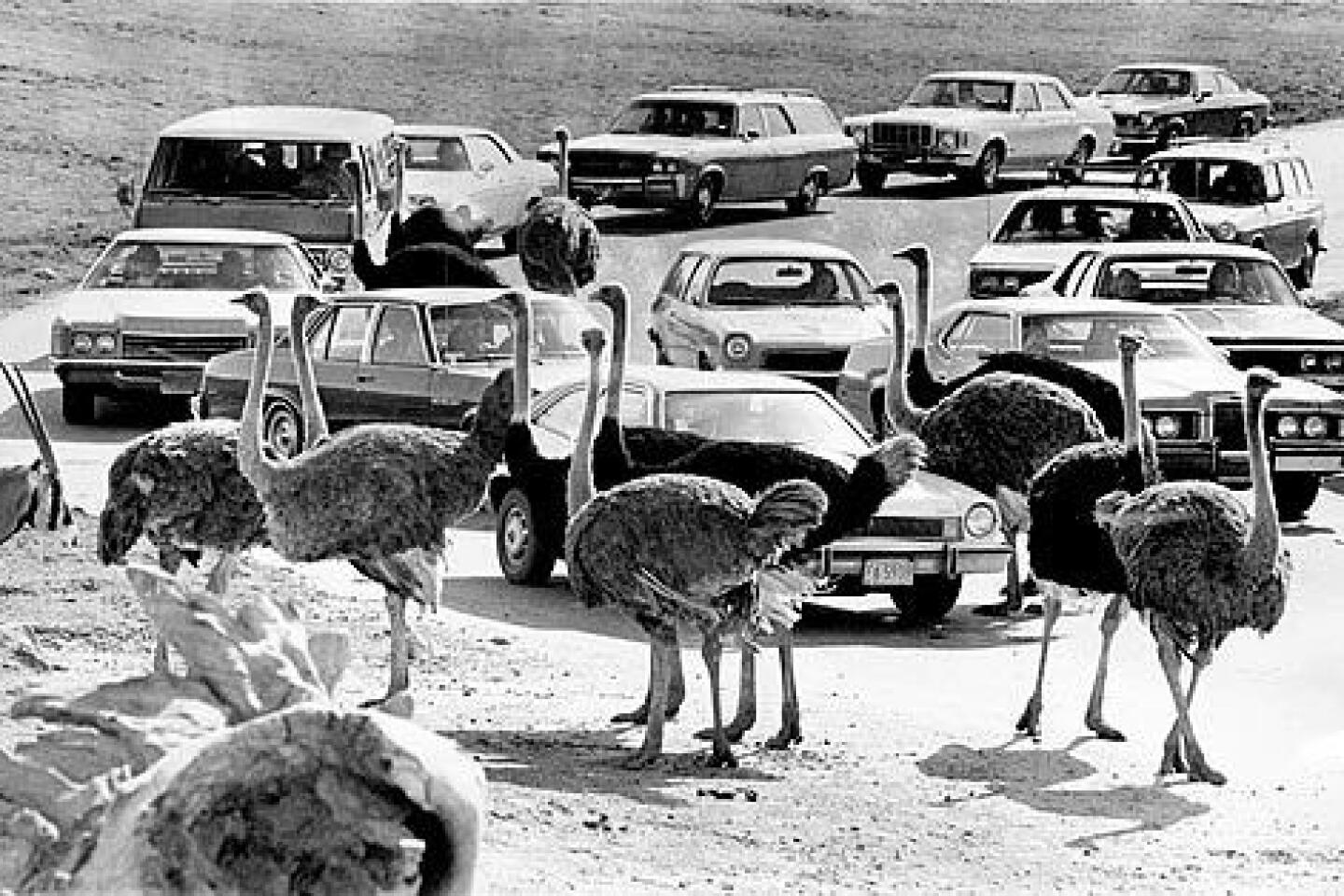

Lion Country Safari

Only in the Hollywood’s backyard could amusement parks turn into captivating theme lands. After popularizing the boysenberry, Walter Knott built Knott’s Berry Farm in 1940 and later brought in buildings from the Mojave Desert ghost town of Calico. Fifteen years later, Disneyland added fairy castles and oversized rodent plushies to the mix. Cha-ching!The real coup in the Southland, however, occurred in 1970 when Lion Country Safari, a South African drive-through zoo concept where the animals are not caged, opened a branch in Irvine. Taking a huge bite — nearly 140 acres — out of Orange County real estate (the site now is home to Wild Rivers and the Verizon Amphitheater), Lion Country Safari was an exercise in the-sky’s-the-limit thinking, plagued by a few unfortunate, don’t mess-with-Mother-Nature incidents.

In 1972, Frazier, the lion king of the Lion Country Safari suburban jungle, expired after two years of stud duty, having sired 33 cubs. Then a worker was killed attempting to capture a wayward elephant. And finally, in 1979, Bubbles the hippo went AWOL and was found holed up in a rain-filled pond. After several days of trying to extract the beast, authorities tranquilized Bubbles, who sank to the bottom of the pond and drowned.

By 1984, the safari was closed, citing losses of nearly half a million dollars in the previous fiscal year.

*

Super California Megaplex Audacious

Despite plummeting movie attendance, the bigger-is-better mind-set still demands cine-cities with more screens than there are weekly releases — and most of them playing “Ice Age 2” and “Scary Movie 4” with eight starting times. AMC Theatre Corp. is king of the steroidal megaplex with its 30-screen extravaganzas in Ontario, Orange and Covina (125,000, 113,000 and 95,000 square feet respectively), but the Edwards chain with its 21-screen theater at the Spectrum in Irvine runs a close second (and with 158,000 square feet, offers a little more leg room). Add corporate cracker-box architecture, hideous interior design, stadium seating and shuttle bus service from the parking lot to the box office — as is the case at the Spectrum — and you have the makings of suburban myth. Hey, can anyone remember where we parked the car?*

Strip Malls

In 1938, Palm Springs made an architectural statement with La Plaza, a handsomely designed boulevard of Spanish Revival buildings with parking that is considered one of the first master-planned shopping centers in Southern California. Not long after, however, planners abandoned any pretense of integrity or design and introduced the strip mall, a cheaply constructed low-rent commercial space that promises convenience yet often offers none. Forget the affront to aesthetics and human dignity and ask yourself this: Do I really want to eat a pizza next door to a dry cleaner?*

Condominio Tuscano

Miles of limestone tile. Gallons of Positano orange paint. Have two more humble materials ever suffered the indignity of being used, over and over, to turn cookie-cutter apartment complexes into shrinky-dink Italian villas?The birth of the McMansion in the 1980s saw a revitalization (some would say bastardization) of almost every European architectural style and period (along with the emergence of catalog companies such as Frontgate to cater to the needs of the over-scaled homeowner). Yet curiously, just as Normandy, Tudor and Plantation neoclassical residences sprang up inside gated communities, condominium developers adapted a somewhat more moderate approach — or so it seemed.

Gravitating toward a generic Mediterranean look, newer condos soon sported red-tile roofs, sunset-colored stucco and stone surfaces on the outside, and delivered sheetrock and sliding doors on the inside. Add wrought iron balconies, lion’s head fountains and potted Italian cypress, and the pizza-box pad soon looked as authentic as the Olive Garden.