1 million people pay nothing for cellphone service, so how does FreedomPop make money?

Half the people using FreedomPop pay nothing for cellphone service, including mobile Internet access.

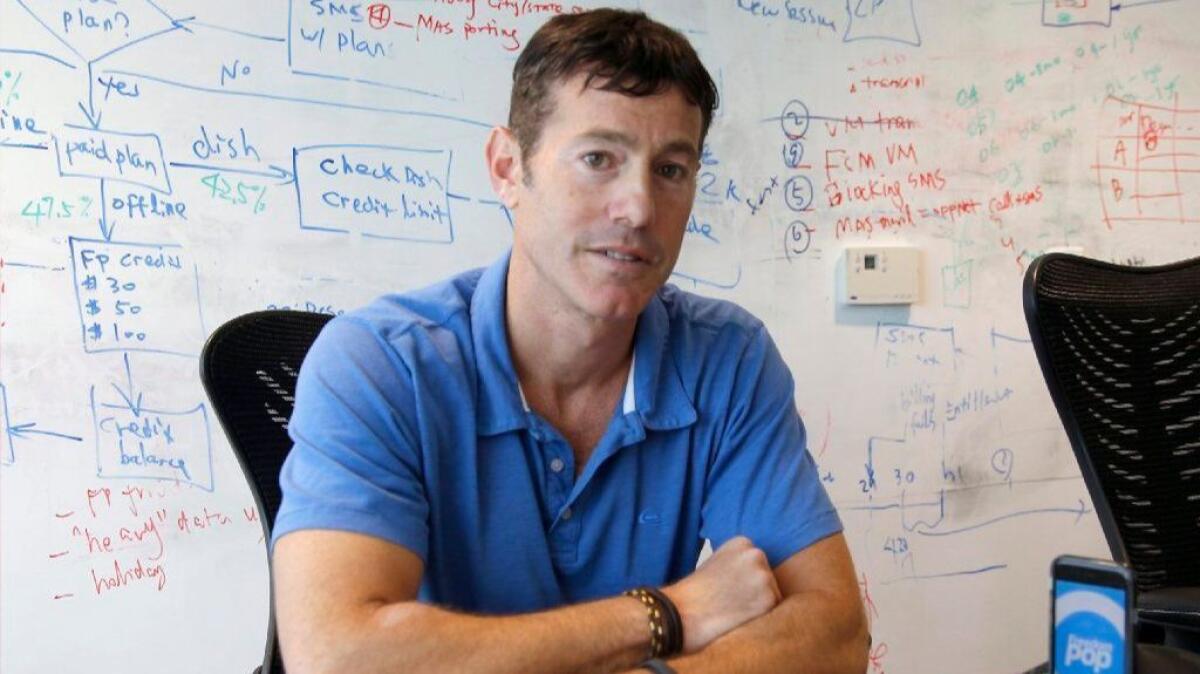

There are times when FreedomPop founder Stephen Stokols would get better coverage or service using a competing cellular carrier. Like when he got booted from his own provider after getting tripped up by confusing settings.

But Stokols — along with his 2 million customers — has been willing to suffer occasional headaches in exchange for an unbeatable deal. Half the people using FreedomPop pay nothing for cellphone service, including mobile Internet access.

There are limits on monthly usage (500 megabytes in the U.S.) and caps on calling and texting (three hours and 500 messages). Finding a shop, reaching a customer service agent or buying a phone from FreedomPop can be complicated. And users need a credit card.

Stokols contends, though, that many should find the trade-offs attractive because he pegs median mobile data usage in the U.S. at about 700 megabytes per month.

Customers can pay a few dollars to pick up extra data, up to about $20 a month for unlimited data, calling and texting. Not a bad deal compared with $40 most elsewhere.

FreedomPop can afford to slash prices thanks to its departures from industry conventions, including accepting lower profit margins.

The Los Angeles company says its emergence over the last six years has led to imitation from T-Mobile, a near-acqusition for as much as $450 million by

Outside the U.S., FreedomPop is licensing technology in Italy and Mexico and gaining users in Spain and the United Kingdom. It’s targeting 100 million users worldwide by 2020, some through partners that collectively have 500 million subscribers.

“Touching 20% of them is not unrealistic,” Stokols says.

But he must decide how far to see through his vision to give away more and more data. The company is reviewing a previously undisclosed acquisition offer, but discussions are continuing about potentially going public next year.

FreedomPop has raised $109 million in venture capital, and the company could become self-reliant soon if, as expected, it generates profit for the first time this winter. Stokols declined to provide specific financial figures.

“We want to get to where communications is a free utility everywhere,” Stokols said. “If you have Internet, you’re at an instant advantage.”

The catch

FreedomPop’s investors say that the company is special because its marketing costs, about $10 per customer, are lower than anyone else’s. Free offers tend to get noticed with little spending on advertising. That lets FreedomPop charge customers less.

Stokols says the company’s goal is to get people paying — not necessarily to twist them into paying as much as possible. “That’s what is different from a typical carrier,” Stokols said.

FreedomPop collects data about users’ backgrounds and phone habits. Stokols said the company can identify who’s likely to be a freeloader who will never pay — and in turn, the company doesn’t waste time pitching such users. Instead it closely studies users who pay for extra features to find new subscribers with similar characteristics who may be more likely to spend in the future.

Some may be open to spending a couple of dollars for data compression, to help them stay under data limits. Others may benefit from international calling and not realize it. The average monthly revenue per paying user is about $15, compared with about $45 at the major carriers.

Some customers have accused FreedomPop of being sneaky with terms and conditions. Stokols acknowledges his company must improve on warning users about forthcoming charges or service suspensions as limits near. He has responded with new self-serve account management tools that reduce the need for customer service agents or stores.

Over the long run, Stokols said, automatically and aggressively responding to customer complaints with refunds or other adjustments is cheaper than having a large customer service crew bickering over small charges. A fed-up customer immediately reimbursed $5 is more likely to spend money in the future and less likely to trash the company online. FreedomPop expects that increased usage of surveys may identify issues before they spread.

Investors say they're not losing sleep over pockets of negative feedback.

“There’s ambitiously excessive desires from consumers,” said Mark Tluszcz of Mangrove Capital, a FreedomPop shareholder. But “when you’re offering a real cheap service sometimes you have to cut corners on service or quality. We have no ambitions to be whiter than white snow.”

FreedomPop tries to prevent itself from being swindled by requiring most customers to have a credit card. “We have no wiggle room for customer service or fraud,” Stokols said.

The company further keeps costs low by holding little equipment. It provides service through free Wi-Fi hotspots and the cellphone towers of Sprint and AT&T.

FreedomPop pays Sprint and AT&T based on customer usage. The two big carriers can see what websites FreedomPop users are checking out, but neither they nor FreedomPop can record or monitor calls as long as only FreedomPop users are participants. This may add a layer of security for users if a legal warrant were to be issued.

Matt Carter, who struck a deal with FreedomPop while overseeing Sprint’s enterprise business, credits Stokols and his co-founders for being among the first to recognize that people were overpaying for data. “They filled a niche for cost-conscious and smart users,” Carter said.

About one-third of new customers buy phones from FreedomPop — mostly refurbished models. That number is falling fast as it’s pushing customers to get devices from retailers such as Amazon and Groupon. Reducing inventory and returns is a cost-saver and valuation-booster.

“We’re trying to look more like a software company,” Stokols said. “We’ve never made a lot of money on devices.”

Overall, the company rakes in gross profit margins of about 15%, or one-third of what’s typical for larger service providers.

The start

Before starting FreedomPop, Stokols sold a video-based dating app called WooMe to dating website Zoosk. The sale wasn’t gargantuan, but investors in WooMe, such as Mangrove’s Tluszcz, decided to issue Stokols several hundred thousand dollars to pursue either a Groupon-type company or a telecommunications start-up.

Tluszcz said he backed Stokols again because he was the rare entrepreneur who saw investors and founders as equal. Stokols could have sold WooMe for less, in exchange for a bigger share of the cash. He instead sacrificed some of his own cut to get a bigger price for WooMe and give its investors a bigger share.

“There’s always temptations when buyers are trying to get a better deal and promising the founder something,” Tluszcz said. “Within those moments, you can see who you can trust.”

Others supported Stokols because of his background as a Tustin-raised entrepreneur who’d spent several years at a big telecommunications firm in Britain. Teaming at the start with Niklas Zennstrom, a Skype co-founder and major European investor, lent Stokols additional credibility.

“He really knew how to do both sides of the fence,” said David Chao, general partner at FreedomPop investor DCM Ventures. “If you get just a telecom guy, you get boxed-in thinking, while an Internet guy doesn’t know how to run a telecom service.”

FreedomPop board of directors

- Stephen Stokols, CEO

- Steven Sesar, chief operating officer

- Mark Tluszcz, co-founder of venture capital firm Mangrove Capital

- David Chao, general partner of venture capital firm DCM Ventures

- Chris Rogers, co-founder and former senior vice president of Nextel

- Mark Menell, general partner of venture capital firm Partech Ventures

Chris Rogers, a FreedomPop board member who has traveled Europe with Stokols for business, described the CEO as a pairing of “surfer demeanor” with “tech aura.”

“When you have an entrepreneur who is the picture of innovation but can communicate with a carrier, that’s really powerful,” Rogers said.

In the boardroom, Stokols is known for going against the grain. He pushed for international expansion when investors preferred U.S. domination first. Stokols told them the company needed more industry relationships, for instance, to broaden the pool of potential acquirers.

Shifting resources hasn’t cost the company because several U.S. rivals shut down in the last year, with many orphaned customers moving to FreedomPop, Stokols said.

He again diversified the business with a new licensing scheme for large carriers to launch cheap plans using FreedomPop’s up-selling and calling technologies. Such arrangements are in operation in four markets, with deals expected to become active in five more regions by year’s end.

As the company heads north of 100 employees, Stokols has tried to preserve FreedomPop’s lean feel. Every employee, including Stokols, spends at least one day a month handling customer service inquiries. He has sent staff to personally deliver phones and handle issues in the Los Angeles area. Of course, all employees use FreedomPop as their carrier.

“You have to be eating your own dog food,” Stokols said.

The efforts are meant to foster an open culture. The idea of rolling over unused data from month to month was introduced by a customer service agent a few years ago, Stokols noted.

He tries to show the same dedication to employees as they show to the company. Early employee Ryan Spillers recalled Stokols taking a Saturday to buy him a bicycle after his was stolen outside the office.

“From that point I was calling him Uncle Steve,” Spillers said. “I don’t know many bosses that would stick their neck out like that.”

Essential to the company’s culture are Fridays at 5 p.m., when a bottle of tequila tells an entire story.

Employees taking shots of Clase Azul, an organic variety that can sell for thousands of dollars, means the company is on track with customer sign-ups. Cheap tequila means it’s been a weak week. Former employees said they appreciated the transparency and camaraderie the gatherings foster. Nondrinkers take water shots.

“You could throw out a $1,000 bonus, and they would be more motivated by the tequila,” Stokols said.

The next frontier

Stokols is concentrating on two fronts. He wants to expand awareness, and he’d like to find new ways to generate revenue.

On the former, the start-up is getting shelf space for SIM cards in Best Buy and other retailers this fall. On the latter, the hope is adding $4 to $7 in average revenue per user by selling ads shown to subscribers.

But the company recognizes growth could stall as competition among the Big Four depresses prices in the U.S. and international carriers smart up to the threat from the likes of FreedomPop.

“They are getting closer and closer to accepting and understanding the culture of Silicon Valley because they have to: It’s just not OK to stand still,” FreedomPop board member Rogers said of top service providers.

T-Mobile and Sprint declined to comment. Verizon and AT&T didn’t respond to requests to comment.

A near-bankrupt FreedomPop was hours away from selling to Sprint in 2015 when a new $30-million investment came in from venture capitalists. Stokols isn’t in a cash crunch this time around.

Investors are equivocal about when to sell, saying that they’ll weigh any offers, like the one on the table now, but that they generally want to see the company remain independent for some time.

If they hold out, investors could turn into potential acquirers. That would include Axiata Group, which has 320 million cellphone subscribers across Malaysia, Indonesia and eight other countries in Southeast Asia. Another investor, LetterOne, has connections to leading cellphone carriers in Russia, Italy and Turkey.

Stokols said he avoids using the company’s original slogan — “Internet access is a right, not a privilege” — because it stirs unease in an industry that generates revenue from charging hundreds of dollars a year for service. But he insists that belief underlies each decision.

The company’s newest plan, launched this week, yet again is challenging industry norms. For $49 a year, customers get 17 hours of calls, 1,000 texts and 1 gigabyte of data each month. “It’s the most data we can give away for under $5 a month,” Stokols said. “We’re getting as bare bones as we can.”

Twitter: @peard33

ALSO

Up from the ashes: Samsung unveils its Note 8 phone

Depressed but can't see a therapist? This chatbot could help

Google's newest Android operating system gets its official name: Oreo

Crowdfunding campaign's goal: Buy Twitter, then ban Trump

UPDATES:

5:30 p.m.: This article was updated to note that Sprint declined to comment.

This article was originally published at 7 a.m.