Fuzz brings more DJs into the online music melee

Pandora has long argued that webcasting royalties are cripplingly high, and tech-friendly members of Congress have periodically sought to rewrite the law to bring the rates down. Nevertheless, companies keep jumping into the market -- the latest being Fuzz, a site that lets people listen to playlists uploaded by other Fuzz users.

Why? One reason is that people respond to the lure of (free) music, both in the giving and in the receiving. So companies can rely on the public to put together the programming, market it to their friends and build an audience for the site, all at little or no cost. Fuzz Chief Executive Jeff Yasuda put it this way: “If you give people a voice, they will work their tails off to really curate and bulid a cool listener experience for their followers.”

In Fuzz’ case, user DJs compete to have their playlists gain a prominent spot on the site. That privilege goes to the playlists attracting the most listeners, that are freshly updated, or that are trending among Fuzz visitors. To create a playlist, users upload songs from their computers to Fuzz, which edits the playlist as needed to comply with the statutory limits for non-interactive webcasting (e.g., songs have to come from multiple different artists and albums).

“We let people curate, then we crowdsource and bring the best stations to the top,” Yasuda said. “The whole thesis behind that is that the best recommendation isn’t one that comes from an algorithm, it comes from a human being.”

But plenty of sites have developed big audiences for online music over the years; the hard part, as Pandora illustrates, is generating enough money to pay the bills. Even if a site minimizes its costs by enlisting algorithmic or (in Fuzz’s case) volunteer programmers, it still has to pay copyright holders for the music it transmits.

Yasuda has a pretty clear idea for how to increase Fuzz users’ engagement with the site. His model is YouTube, where he says roughly 1% of the audience uploads content, 9% comments on it and 90% simply watches it. Fuzz gets people in the door by offering “cool, curated music,” as Yasuda put it. After people listen to a few stations, the hope is that they’ll leave a comment or give a “prop” -- the Fuzz equivalent of a Facebook “like” -- to the DJ. That may trigger more interaction between users and DJs, eventually prompting more users to upload their own playlists. “Once we’ve got you actually curating music, the switching costs get pretty high,” Yasuda said.

OK, so assume Fuzz attracts a lot of users and persuades many of them to spend too much time there. How does it translate that into revenue? On that point, Yasuda is more, ahem, fuzzy. Yasuda said the company is pursuing a “freemium” model, with the free version acting as a gateway drug to the paid version with additional features and content. He provided few specifics, other than to say that he thinks the main opportunity is in mobile and such things as in-app purchases and gaming.

His previous venture, Blip.fm, was an advertiser-supported online music venture, and Yasuda said that it is, in fact, profitable. But he also said: “The advertising model is a pretty tough hill to climb. So we’re looking for different ways to monetize.”

Fuzz hopes that its wide selection of playlists created by music fans will help distinguish it from the likes of Pandora, but it’s hardly the only human-powered music service out there. Live365 is the granddaddy -- it offers a slew of webcasts by DJs of all stripes, including professionals. Then there’s Slacker, which combines algorithms with human programmers to develop superior playlists based on the listener’s personal tastes. Meanwhile, there’s a profusion of personalized webcasts a la Pandora and a growing number of on-demand services with limited free tiers, a la Spotify.

As Yasuda acknowledges, Fuzz is entering “the toughest space on the planet.” And the one sure thing about it is that every new user who hits the “play” button on a Fuzz station costs the company about a penny for every nine songs streamed. That’s today’s royalty rate; the amount is set to increase annually. If Fuzz stays small, it can pay the copyright owners 10% to 14% of its revenues in lieu of the per-song royalties. But once it passes $1.25 million in annual revenue, it has to pay for each stream. (Thanks, as ever, to David Oxenford and his Broadcast Law Blog for the royalty breakdown.)

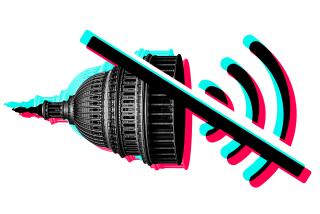

Some lawmakers are trying again to bring webcasting royalties into line with the lower fees paid by other digital radio services. Their effort has drawn opposition, naturally, from the music industry, which is simultaneously trying to persuade Congress to require over-the-air broadcasters to start paying royalties to recording artists and labels. There’s potentially a grand bargain to be had, but it’s more likely that the status quo will remain in place at least until Fuzz has burned through the roughly half-million dollars Yasuda has raised from angel investors.

On the plus side, several of Yasuda’s backers are well versed in the challenges of the online entertainment business and content licensing, including Mika Salmi (ex-Atom Films and MTV digital media) and Ali Aydar (ex-Napster, Snocap and imeem). And Fuzz is fun, simple to use and an intriguing way to discover music, so it may very well attract a big audience. That’s a necessary ingredient in Fuzz’s survival, although it’s not sufficient.

ALSO:

How to merge Facebook contacts with your iPhone 5

Myspace previews redesigned site: It’s pretty, but will it work?

Tablet maker sues Toys R Us over kid-oriented tablet computer

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey