Paper records and steel vaults: Can California water rights enter the digital age?

From an unremarkable office in Sacramento, Matthew Jay can pinpoint any moment in California history when somebody was granted the right to transfer water from any particular lake, river, stream or creek.

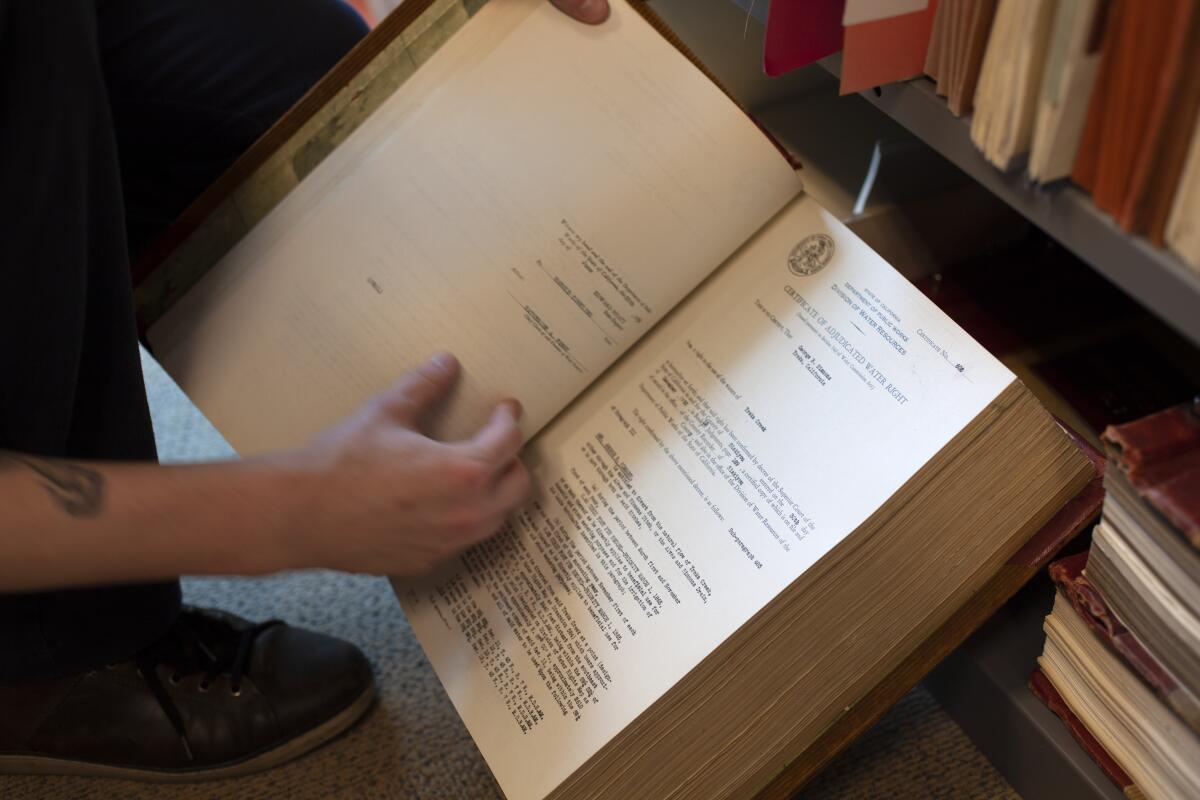

An analyst with the California State Water Resources Control Board, he is a custodian of millions of pieces of paper. Some are over a hundred years old and are crammed into towering filing cabinets and vaults. The room is so heavy that its floor needed to be reinforced.

“When I started opening some of these files my first thought was: ‘I need to be very careful with these old, old documents.’” Jay said. “They’re printed on an equivalent to tissue paper.’”

But in the world’s fifth-largest economy — a state where global warming is contributing to ever longer and more frequent droughts — regulators say reliance on such an antiquated system is troubling. They say the lack of a comprehensive digital system and full information about who owns the right to use water and how much they actually use makes basic water management in the state mystifying at best, and inaccurate at worst.

After 13 years of working in the records room, Jay can easily rattle off the most notable water users documented there: There’s Mike Yurosek, inventor of baby carrots. Coppola Wineries, the vineyard started by Francis Ford Coppola after his blockbuster “Godfather” trilogy. And Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District, which funnels enough water to rice farmers north of Sacramento to supply the city of Los Angeles several times over. Yet researching the location of every water right granted along a waterway like the Shasta River can take up to a year to complete.

Despite a California law intended to end over-pumping of aquifers, a frenzy of agricultural well drilling continues in the San Joaquin Valley.

California’s Byzantine system of water rights dates back to the Gold Rush, when miners declared their rights to water by nailing paper notices to trees. The oldest rights holders have seniority, and when the state restricts water use in times of drought, these senior rights holders are last to be curtailed, if at all.

California’s lack of timely and useful data became all too apparent during the 2012-2016 drought and prompted new regulations that populated a clunky data portal with new water use information. But problems remained during this most recent drought, as regulators used outdated and incomplete data to issue curtailments this past summer.

“We’re behind the curve on this in a way that’s really shocking,” said Felicia Marcus, former chair of the water board under Gov. Jerry Brown and visiting fellow at Stanford University. “In the absence of workable data, people can say whatever it is convenient for them to say. So let’s get the data. That’s how all good water management works.”

This year, Gov. Gavin Newsom approved $33 million as part of a surplus budget to modernize California’s water rights information system. It’s the latest effort in an uneven regulatory history that has sought to make water use in the state more transparent.

Erik Ekdahl, a deputy director at the state water board, said the process of combining water supply information from the Department of Water Resources, water rights documentation from the records room, spotty demand data reported by users themselves, and environmental needs for every watershed, is tedious and convoluted.

The Kern River has long been a dry riverbed in downtown Bakersfield. A group of residents is pushing to bring back a flowing river.

The forthcoming data system, currently in a contracting phase, will be mapped, searchable, and include water diversion and rights information at the click of a button. The idea is to create a spatial image of California’s water use, with an ultimate goal to set up a telemetry system where water meters are directly connected to the internet.

“This isn’t a changing climate, this is a changed climate… We should expect to be doing curtailments again, and maybe more frequently, maybe in two years, maybe next year,” Ekdahl said. “Right now we make data-driven decisions, but the data comes at a great time and expense. We’re setting the stage for making all this information actually accessible and creating the opportunity for people to make data-driven decisions themselves.”

California’s water data problems don’t end with the digitization of paper records, information that’s mainly used for long term planning. The state is uniquely in the dark about how much water gets used, and by whom, in a given moment compared with other Western states like Colorado. That is particularly the case with agriculture — the $50-billion industry that uses roughly 80% of surface water supplies.

It was 2009 when the state issued mandates for urban and agricultural water districts to report how much water they deliver to their customers — by snail mail — without using a meter. By 2015, a new law required even more water users to measure and report yearly how much water they take from waterways.

But since that law took effect, fewer than 20% are complying according to a long “deficiency list” of rights holders who have failed to respond. An even lower percentage are following the latest reporting rules passed in the last couple years, according to the water board.

The data has glaring errors, like numbers reported in acre feet instead of gallons, and it’s a year old by the time regulators use it. Laws that govern California water may also incentivize users to claim more than the share of water they actually use, known as the “use it or lose it” doctrine.

That’s why Michael Kiparsky, director of the Water Wheeler Center at UC Berkeley, says the forthcoming system is only a step in the right direction toward effective California water management. His team researched water rights data to build a prototype — scanning, digitizing and assigning metadata to over 130,000 pages of water rights documents from the Mono Basin.

“Hopefully this database will be a piece of the puzzle that will enable people to start unlocking new ways of managing water in California that could get us to a less painful future,” Kiparsky said.

Even if it’s finished in a breakneck pace of two years, the technical and cost barriers to reporting information in rural areas as well as reticence to share information with the government will remain.

A water law attorney who represents water districts and farmers is skeptical that regulators will take quicker and better informed action in times of drought, despite access to more information.

“You have a whole group of people that have the data. They live with the data, and they don’t really trust the board to do anything good with it. They’re not thrilled about reporting because they’re afraid it’s going to be used against them,” they said. “There’s a big trust issue.”

A new technological venture using satellite-based estimates of evapotranspiration to measure water aims to be a less invasive and cost-free means for farmers to send in data. The organization, called OpenET, is a collaboration between NASA, Google Earth and the Environmental Defense Fund.

Brett Baker, a fifth-generation farmer in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and attorney representing the Central Delta Water Agency, is familiar with those longstanding trust issues and hopes the new outside technology can satisfy farmers’ reporting requirements.

“Hopefully that will satisfy the reporting requirement and enlighten their understanding,” he said of the water board. “I think this is a real opportunity for us to start operating in reality with real useful data, as opposed to just making stuff up to fit the narrative.”

Matthew Jay, in the meantime, will help the water board digitize the water rights system as a kind of records consultant, and keep doing the most rewarding part of his job — helping people learn about water rights.

“It’s about providing that customer service to folks, so they can do the research and inform themselves of what water rights there are on a property,” he said, and just making people aware that water rights exist in the first place.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.