Review: Gustavo Dudamel and Bolivar symphony bring Beethoven’s revolutionary conviction out in force

Upon hearing the news of Napoleon declaring himself emperor of France in 1804, Beethoven supposedly flew into a rage and violently scratched out the dedication on the manuscript of his new Bonaparte Symphony. Beethoven’s Third — the symphony that changed music through its radical scale and the conviction that symphonic music could serve as a force for narrative and democracy — became, instead, the “Eroica,” an idealistic exhortation for the overthrow of oppression.

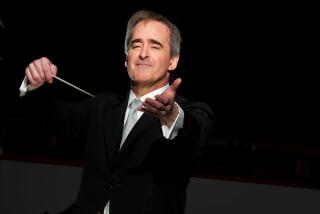

Friday night at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Gustavo Dudamel changed the symphony’s name again, in spirit anyway, this time from “Bonaparte” to “Bolívar.”

In terms of conveying the immediacy of Beethoven’s revolutionary conviction, this was the most convincing performance I have encountered live or via recording or broadcast. That is not to say any performance, however stirring, could be the greatest; such a superlative trivializes the cultural and musical depths of a great work. What was on display here, though, was an incomparable sense that this is music that matters, and the way to show that it matters is to play it with the commitment of an overwhelmingly disciplined and efficient army, inflamed with passion, undefeatable as it marches into noble, necessary battle.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

The performance was by the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela, which is sharing the cycle of nine Beethoven symphonies with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. The night before, Dudamel had begun with the more conventional first two symphonies in elegant readings with the L.A. Phil that in no way prepared a listener for the terrifying force of the Bolívars playing the Third, or, after intermission on Friday, an outrageously visceral performance of the normally less explosive Fourth.

Saturday afternoon, the L.A. Phil probed the Fifth and Sixth. In the evening the Bolívars turned the Seventh and Eighth into symphonic rock ‘n’ roll. The cycle was to continue Sunday with both orchestras combined for the Ninth (to be reviewed later). After repetitions of the Ninth on Tuesday and Wednesday, the cycle repeats beginning Thursday.

For the weekend’s Beethoven performances, the Bolívars scaled down their normally enormous size to fewer than 100, still slightly large for Beethoven, with double winds, but not unreasonable. The playing was physical, as it always is, but the players, most in their early 30s now, don’t sway as extravagantly as they once did when this was a youth orchestra.

But the ensemble virtuosity is greater than ever. These are symphonies that the musicians have been playing together since they were kids, and the notes are in their muscles the way movement is in the muscles of ballet dancers. They watch and react to one another almost as much as they do the conductor.

Their command is such that the Bolívars can be a scary unified force, and they ferociously tore through the last movement of the Seventh Symphony taking no prisoners. Yet they just as readily exulted in extreme delicacy and quiet. When a solo passage came up, such as for the clarinet in the slow movement of the Fourth, the playing had the distinctive individuality of a momentary jazz solo, giving the sense that every note was being played for the first time, that everyone was in the moment.

There is deeper meaning, however, to this Bolívarization of Beethoven.

It is no coincidence to connect Venezuela’s “El Libertador” with the “Eroica.” As a young man visiting Paris, Simón Bolívar witnessed Napoleon’s coronation. Disillusionment with the so-called revolutionary is what helped to fire Bolívar’s republican fervor, which eventually led him to lead a rebel army against Spanish rule in South America.

That the “Eroica” is personal to the Bolívars goes without saying, especially now when the Bolívarian revolution in Venezuela appears to be fragile, what with the nation’s political discontent and economic chaos. Although they refer to one another as amigos and the orchestra is dependent on government support, the musicians are divided in their political affiliations in a dangerously divided country.

Dudamel’s secret for keeping the players a loyal band appears to be shock therapy along with acting as a supplier of a high-grade adrenaline stimuli. The impact of the sudden first two chords of the “Eroica” got everyone’s attention; orchestra and audience were instantly in Dudamel’s hands. By the time he reached the end of the Eighth, the next evening, the adrenaline rush had taken full effect.

Beethoven’s “Egmont” overture, with more Bolívars coming on stage for a big-bang big band effect, was also personal. This overture to Goethe’s drama happens to be about overthrowing Spanish rule and (take this as you will) oppressive government. It was a phenomenally powerful performance, far more so than the one four nights earlier with the Bolívars joining the L.A. Phil for the season-opening gala.

Dudamel has given us compelling performances of the famously forceful Fifth Symphony and the seductively luminous Sixth (“Pastoral”) with the L.A. Phil. At Saturday’s matinee, the playing was beyond reproach.

The L.A. Phil is capable of greater polish and refinement than the Bolívars, but the urgency of Bolívar Beethoven is unique. Beethoven stands for Simón Bolívar in Venezuela, and for Venezuelans, Simon Bolívar represents liberation. Musically, these Beethoven performances serve at handbooks for all of us for finding the exhilaration of freedom through discipline, devotion and fine-tuning earth-shaking energy.

------------

Beethoven symphony cycle

Who: Los Angeles Philharmonic and Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra

Where: Walt Disney Concert Hall, 111 S. Grand Ave., Los Angeles

When: Ends Sunday

Tickets: $26.50-$213.50

Info: (323) 850-2000 or www.laphil.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.