Review: Cristian Macelaru gets a big sound from the L.A. Phil as it plays Rachmaninoff

Walt Disney Concert Hall is, as always at this time of year, decked out for Christmas and Hanukkah and in glittery expectation of New Year’s Eve. Meanwhile, on Friday morning, the obdurate Los Angeles Philharmonic offered, as it typically does this time of year, no overt acknowledgment of holiday glad tidings or piety. The first of three performances of the orchestra’s final program of the year was a morning of melancholic Rachmaninoff.

Melancholy does, of course, suit the season. We think back about what we’ve lost, what went wrong. We are reminded we’re a year older. We look forward and fret, something orchestras do quite well. World-class worriers, they agonize over where the next audiences will come from and whether technology will kill traditional concerts. For decades, doom has seemed a downbeat away.

SIGN UP for the free Classic Hollywood newsletter >>

The L.A. Phil’s gift this season, however, is otherwise. Its stellar music director, Gustavo Dudamel, is still only 34. Most of the other conductors this fall have been up-and-coming twentysomethings and thirtysomethings so accomplished that we might as well just relax. These, along with several others, offer assurance like never before that the next generation of leaders is in the wings.

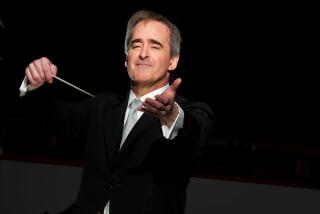

Friday, it was Cristian Macelaru’s turn. The impressive Romanian conductor in residence of the Philadelphia Orchestra is a year Dudamel’s senior. Last month he made his New York Philharmonic debut beginning that orchestra’s three-week Rachmaninoff festival. His San Diego Symphony debut next month presumably puts him in the running for the orchestra’s music director search, in competition with the L.A. Phil’s young assistant conductor, Mirga Grazinyte-Tyla (the City of Birmingham Symphony, in immediate need of a music director, is also eyeing both).

What makes Macelaru impressive is the huge sound he gets from the orchestra. It is so big that one might have questioned whether the row of small loudspeakers on the lip of the stage, left over from a pre-concert talk, had been accidentally left on. They weren’t; were loudspeaker technology to reproduce that kind of sonic magnificence, orchestras really would have something to worry about.

The concert opened with Rachmaninoff’s orchestration of his Vocalise, one of the world’s more popular melodies and, in fact, the kind of bonbon that would not be out of place on a New Year’s Eve pops concert. Macelaru would have none of that. He sought boldness, as though wrapping the hall in a thick, heavy velvet Rachmaninoff bow that implied a gift of some extravagance and possibly decadence.

The Second Piano Concerto is more popular (and pop) Rachmaninoff. If you’ve been thinking about Frank Sinatra lately (what with the attention to his centennial), you may have come across his early hit “Full Moon and Empty Arms,” based on a melody from the concerto’s slow movement. Bob Dylan has made the torch song newly fashionable, singing it on his recent album “Shadows in the Night.”

The soloist was Kirill Gerstein, a Russian pianist with a wide perspective who has used some of his Gilmore Artist Award prize money to commission new works from jazz pianists Chick Corea and Brad Mehldau. In Rach 2, pianist and conductor went for full moon and full arms.

This was Rachmaninoff playing on the grand scale. The opening solo piano crescendo had the quality of a cymbal crash; once started, the sound seemed to grow with a life of its own. Gerstein brought power and fascinatingly idiosyncratic phrasing to the fistful of figurative piano writing. Macelaru would have drowned out a lesser pianist, but Gerstein held his own. Lyric melodies were plenty slow but didn’t linger. Everything else was granitic and gargantuan. The audience got excited.

For the Symphonic Dances, Rachmaninoff’s last major work and his greatest orchestral score, Macelaru further increased the dosage of orchestra steroids. Even so, details came through well. The rich string playing and wind playing may have been inspired by Macelaru’s work with the Philadelphia Orchestra; the brass blowout had the Chicago Symphony written all over it. The L.A. Phil responded spectacularly.

But as in a blockbuster in 3-D Imax virtual-reality whatever, the big-deal special effects become predictable after a while. Macelaru knows how to get attention like few of his peers. He’s now in an enviable position of being ready to figure out what to do with that great skill.

And for that he might have had no better instructor than clarinetist Michele Zukovsky, who retired Sunday after 54 years in the orchestra.

A noted musician in the audience Friday told me that he learns something about creative rubato every time he hears Zukovsky play.

The orchestra’s president and chief executive, Deborah Borda, just finishing up a sabbatical teaching at Harvard, emailed a haiku she had written to be read at Sunday’s matinee: “Burnished, glowing sound/notes laughing, lightly floating/Play on dearest friend.”

There weren’t many clarinet solos in these Rachmaninoff pieces, but Zukovsky’s familiar burnished tone, creative playing and laughing spirit were unmistakable. She leaves on a glowing high note.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.