‘From Hollywood to Nuremberg’: How three noted filmmakers used their cameras to document Nazi atrocities

Some of Hollywood’s biggest stars fought during

A new exhibition at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust, “Filming the Camps: John Ford, Samuel Fuller, George Stevens, From Hollywood to Nuremberg,” revolves around the concentration camp footage captured by these three directors.

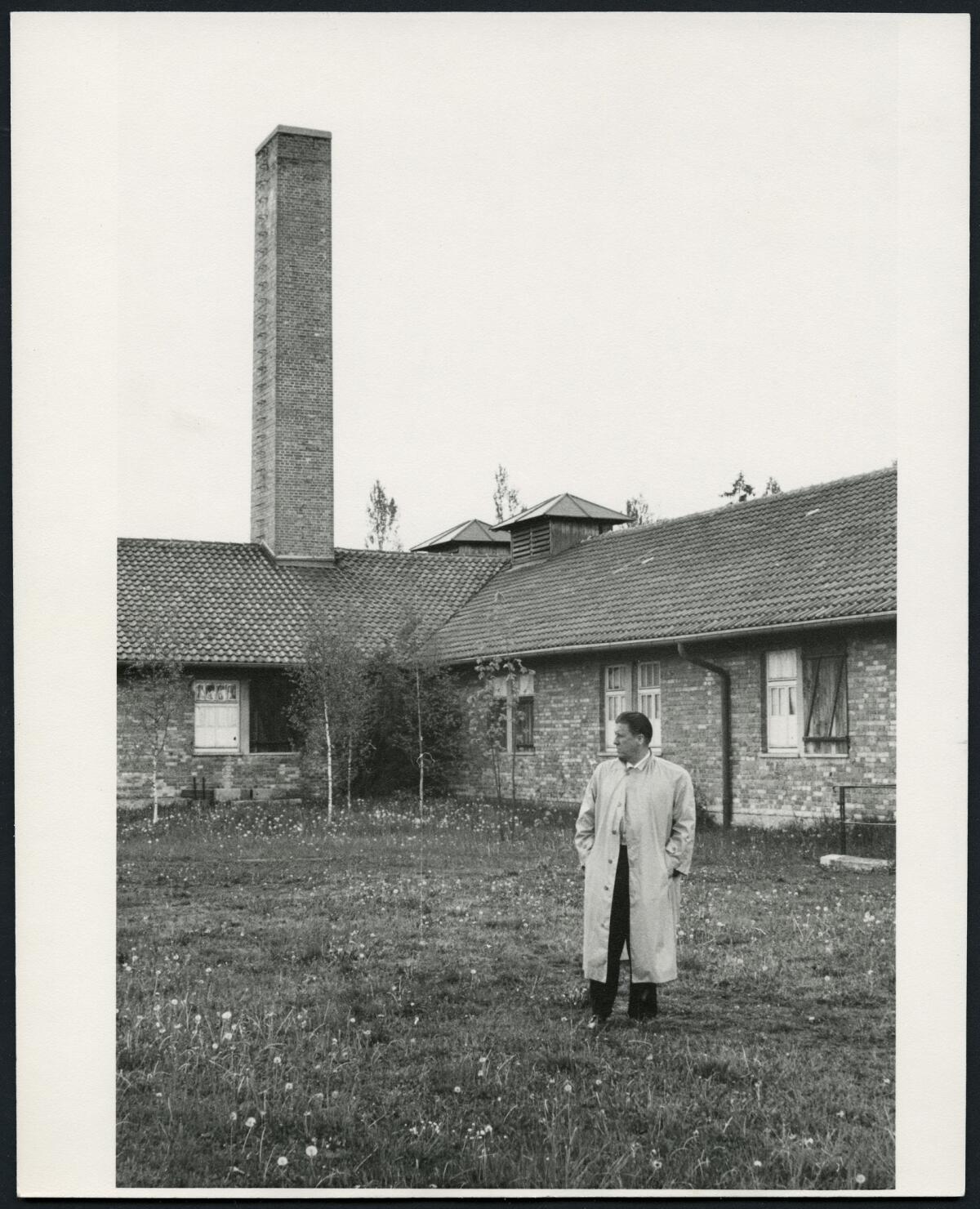

Created and circulated by the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris and curated by filmmaker and historian Christian Delage, “Filming the Camps” presents rare footage of the liberation of Dachau, burials at Falkenau and documentary footage for the Nuremberg trials after the war.

“Our museum is unique, because we teach the L.A. narrative as part of when we talk about the Holocaust,” said Executive Director Beth Kean. “We have the front pages of the L.A. Times from 1933-1945 throughout the museum. It’s very appropriate and fitting to have this exhibit here about three directors who made their mark here. People think the war happened halfway across the world, when it did in fact impact people living here.”

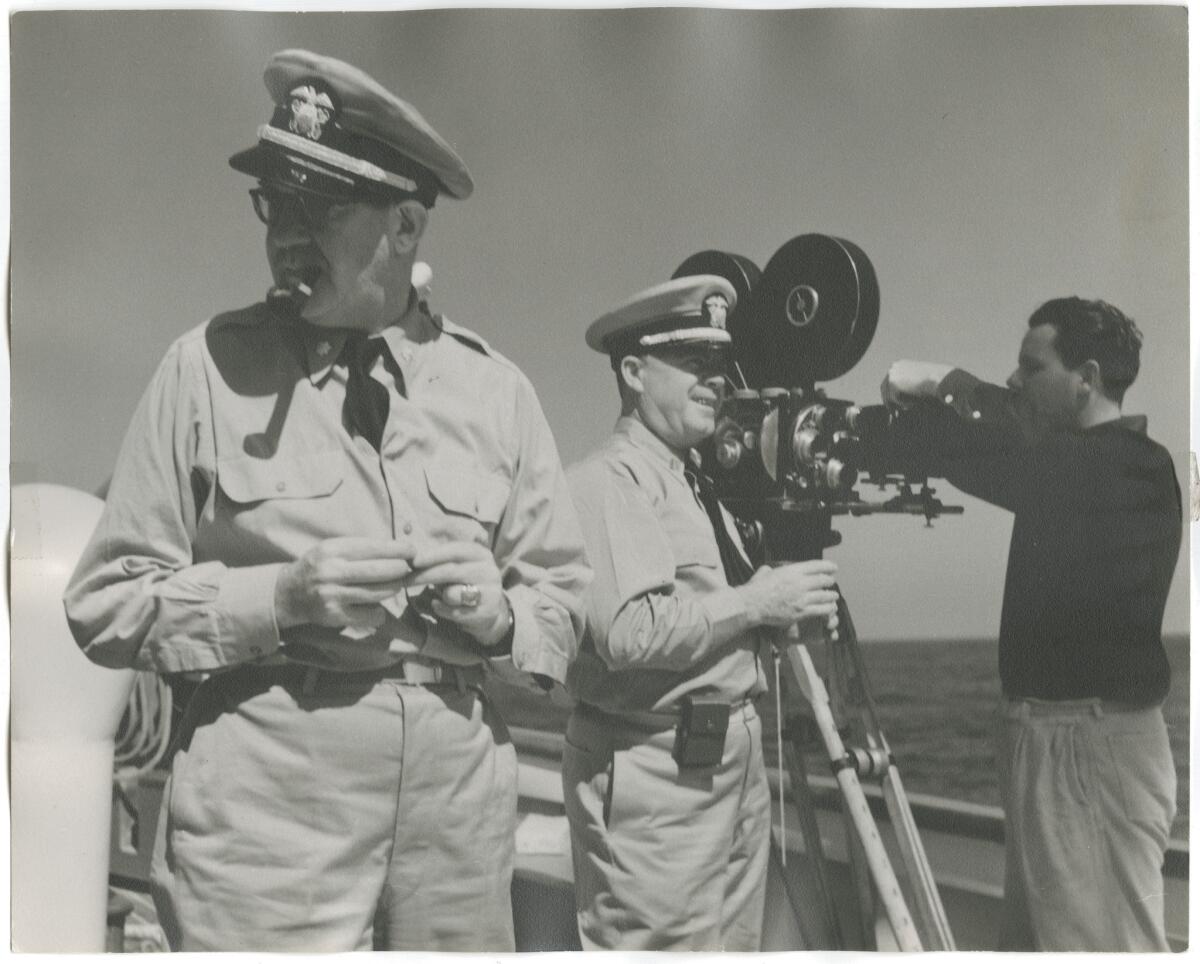

Ford, who had won Oscars for directing 1935’s “The Informer,” 1940’s “The Grapes of Wrath” and 1941’s “How Green Was My Valley,” served in the Navy and was head of the photographic unit for the Office of Strategic Services.

Stevens, who had directed such classics as 1935’s “Alice Adams” and 1943’s “The More the Merrier,” headed a film unit under Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower as a member of the Army Signal Corps and documented D-day, as well the liberation of the Duben labor camp and the Dachau concentration camp, both in Germany. That footage and other concentration camp film was presented at Nuremberg.

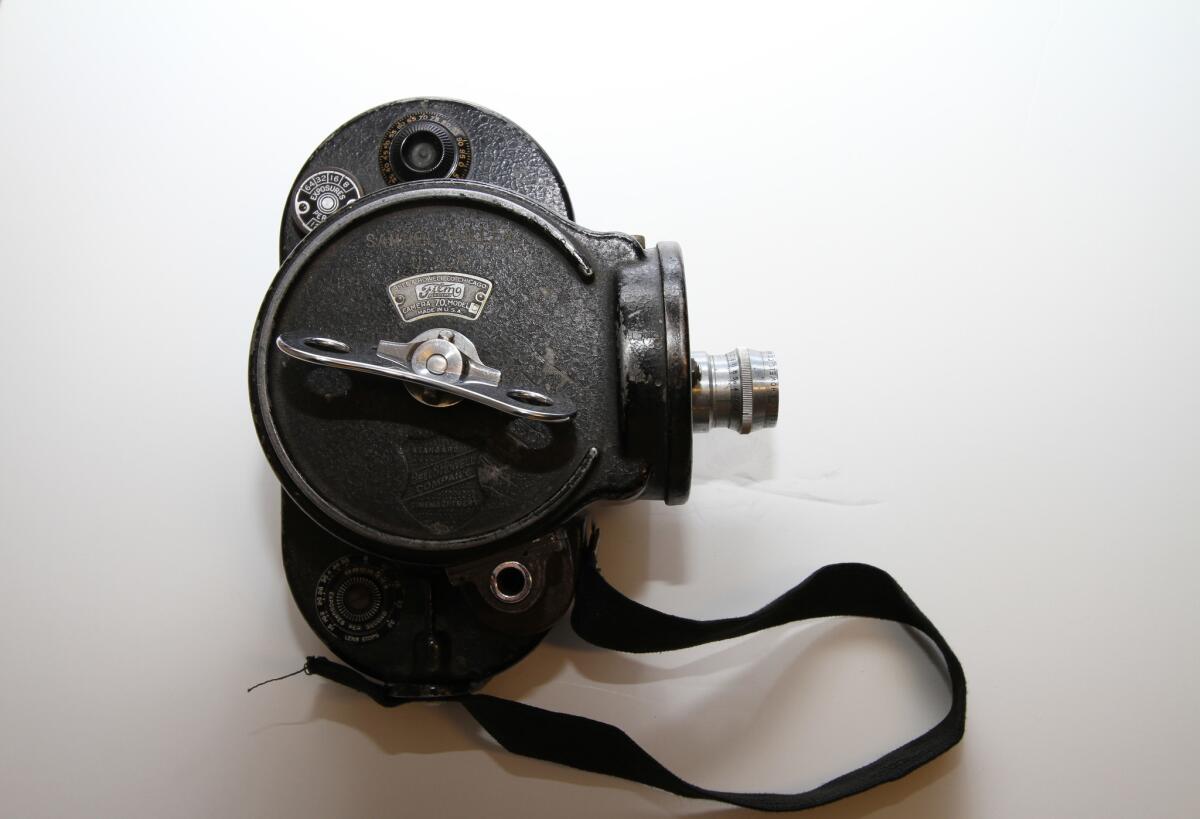

Fuller, who directed such gritty war films as 1951’s “The Steel Helmet” and 1980’s “The Big Red One,” wasn’t a filmmaker during World War II but an infantryman who shot the harrowing 16mm footage of Falkenau in what was then Czechoslovakia.

“Fuller was not a member of the team, so it’s a personal story,” Delage said.

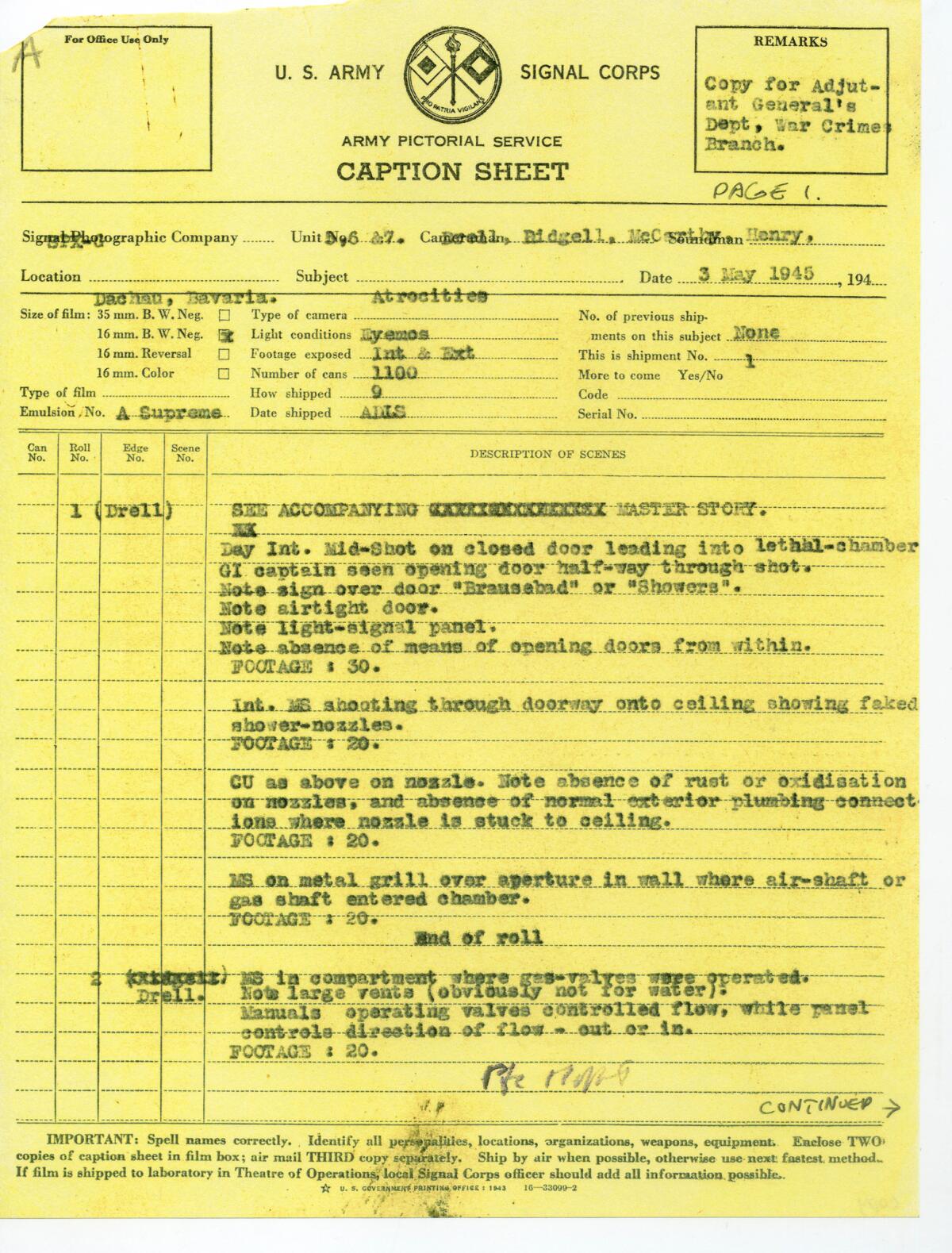

The exhibition also shows how photographs and film footage were shot to document history.

“There was a specific process that had to take place,” Kean said. “The exhibit shows what procedures these men had to take. They had to prove the authenticity of what they had taken. They had to prove that it actually happened. That’s what Christian wanted to point out. Everything was deliberate. The way they took the photographs, the angles … so they could be used as evidence. People don’t realize it.”

Stevens’ feature films after he returned from the war were much more dramatic and serious than his prewar comedies. He won Oscars for 1951’s “A Place in the Sun” and 1956’s “Giant” and earned a nomination for the 1959 World War II film “The Diary of Anne Frank.”

Stevens was the most touched by what he saw during the war, Delage said. “He was not a soldier like Fuller, and he was less a tough guy than Ford was.”

“Filming the Camps” continues at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust through April 30.

MORE ARTS COVERAGE:

With raw eggs and clay, Anna Maria Maiolino makes art about being a woman

Why David Geffen pledged $150 million for new LACMA building

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.