Novelist Gabriel García Márquez wrote a western in the ‘60s — it screens in Hollywood on Friday

A man returns to the dusty village of his youth after an 18-year absence. A couple is fleetingly reunited after decades apart. A pair of hot-headed brothers seeks to avenge a murder they neither witnessed nor fully comprehend. There is a gun battle.

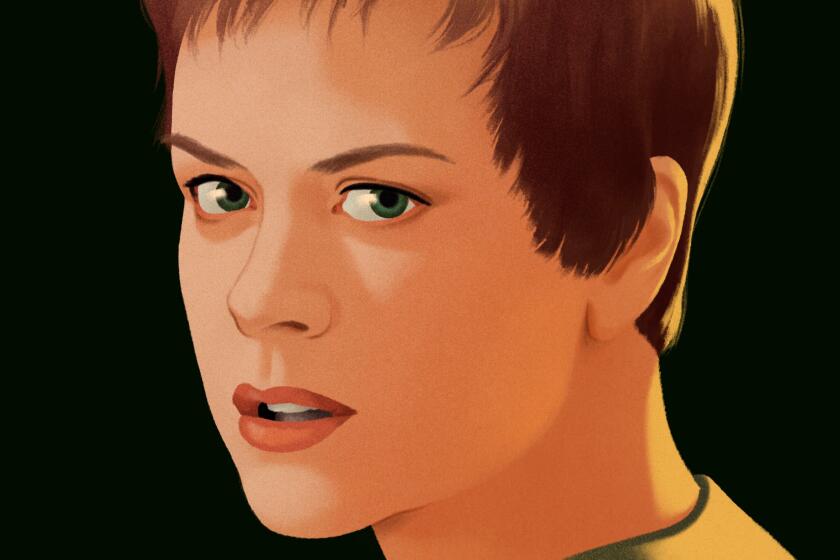

In many ways, “Tiempo de Morir” (“A Time to Die”), the 1966 debut drama by Mexican filmmaker Arturo Ripstein, a protegé of Luis Buñuel, fits squarely within the category of western — in which life-and-death issues of honor and justice play out amid lawlessness and parched landscapes.

But the film may be most notable for the writer behind its screenplay, a former journalist from Colombia by the name of Gabriel García Márquez.

Before “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” the novel that would change his life and the world of Latin American letters, before the Nobel Prize for Literature, before he got into a legendary, mysterious fistfight with Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa, García Márquez worked as a screenwriter. He wrote the story “Tiempo de Morir” at Ripstein’s request and then adapted it for film with the help of a friend, who happened to be the Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes.

The film touches on many of the themes that would materialize in García Márquez’s fiction — tradition, propriety, fate. It is a story of vengeance that is also at its essence about the dynamics of family. And there is the setting that feels as if it’s at a remove from reality.

Now this early cinematic work is getting a rare public viewing in Los Angeles.

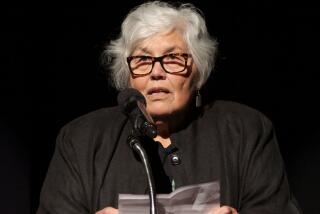

To mark the 50th anniversary of the film’s release, Libros Schmibros, the nonprofit lending library based in Boyle Heights, has organized a one-night, outdoor screening at the Ford Theatres in Hollywood on Friday night. Introducing the film will be the author’s son, filmmaker Rodrigo García (most recently of “Last Days in the Desert,” starring Ewan McGregor).

“I love the simplicity of the story — yet it still has power,” García says of his father’s film. “It’s a guy who returns home after serving time after killing someone in a duel. He thinks it’s over. But the dead man’s sons don’t think it’s over. It has this Greek tragedy aspect to it — that your future is already written. You can’t escape your past.”

David Kipen, founder of Libros Schmibros, says he wanted to bring “Tiempo de Morir” to Los Angeles, “not just as García Márquez’s film, but as a debut work of an important filmmaker.” He also points out that along with the directing of Ripstein, moviegoers can take in “the great work of the cinematographer Alex Phillips and the composer Carlos Jiménez Mabarak, who did the score.”

It has this Greek tragedy aspect to it — that your future is already written. You can’t escape your past.

— Rodrigo García, on “Tiempo de Morir”

For Kipen, the showing also represents an opportunity to do something different from the panoply of outdoor summer screenings held around Los Angeles, which are strong on “Pretty in Pink” and “Pulp Fiction,” but not so hot when it comes to presenting historic Mexican film (or Mexican film in general).

“I want to show that there is an audience for more than ‘Top Gun,’” he says, “for something entertaining, literate, literary.”

“Tiempo de Morir” doesn’t make appearances on best-movies lists. But it is a beguiling picture nonetheless — a simple story, simply told and elegantly shot, about an honorable man named Juan Sáyago, who becomes mired in events that are beyond his control.

As a historical document, the film is fascinating, embodying the Nobel Laureate’s long-running love affair with cinema.

As a journalist in Colombia in the early 1950s, García Márquez had written film criticism under the pseudonym Septimus for the daily El Heraldo in Barranquilla. Captivated by the work of the Italian neorealists, his first review was of Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 classic “The Bicycle Thief,” about a poor man trying to locate his only means of transportation.

It was around that time that he began to try his hand at filmmaking. He co-wrote the screenplay for a surrealist short titled “La Langosta Azul” (“The Blue Lobster”) — about a man investigating the appearance of some mysterious radioactive lobsters.

Sign up for our free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

In 1961, taken with idea of becoming a screenwriter, he moved to Mexico. “At the time, the Mexican film industry was very vigorous and it sustained itself,” says García. “People in Mexico went to see Mexican movies assiduously. And those movies traveled very well throughout Latin America and Spain.”

Throughout this period, García Márquez bounced back and forth between fiction and film, publishing early works such as “The Leaf Storm” (1955) and “No One Writes to the Colonel” (1961), but also working on various screenplays — including the script for the 1964 morality tale “El Gallo de Oro” (“The Golden Rooster”) and “En Este Pueblo No hay Ladrones” (“In This Town There are No Thieves”), which was based on one of García Márquez’s own short stories.

The latter, in fact, featured an appearance by the author, as well as appearances by Buñuel (playing a priest), the novelist Juan Rulfo and the painters José Luis Cuevas and Leonora Carrington.

Sometime in the middle of the decade, the author teamed up with Ripstein to do a western. “I was writing this terrible script and I asked him if we could do a story together,” Ripstein told the Mexican newsweekly Proceso in 2014. “He wasn’t so well known then.”

That story was “Tiempo de Morir.”

“The town [in ‘Tiempo de Morir’] is populated by like nine people and they are surrounded by blasted desert,” Kipen says. “If you read García Márquez novels, ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude,’ the rural settings — you get the sense that places like Macondo are a place apart.”

But above all, there is the sense that individuals can’t escape destiny. In “Tiempo de Morir,” the lead character’s impending death is ultimately what gives the film its tension. The viewer knows it is coming — it’s announced right at the beginning.

The author’s 1983 novel, “Chronicle of a Death Foretold,” is also about a man fated to die. And the opening line of the transformative “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” which came out a year after “Tiempo de Morir” premiered, also points to inevitable outcome: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

“His work had many aspects, but one aspect is precisely that — that something is already written,” says García. “A man wakes up in the morning and doesn’t know that he is already dead. And there is nothing, no good luck or effort or intelligence that can prevent that.”

“[My father] was always very open about his love for Oedipus Rex,” he adds, “which is very much a story about fate.”

“Tiempo de Morir” premiered at the Cine Variedades in Mexico City in August 1966. But it was never a great commercial success.

Though beautifully rendered, the dialogue is rather formal, almost arch. Decorous dialogue works well in García Márquez’s novels, where characters clinging to tradition face the extraordinary and the bizarre. But it didn’t work as well on screen — where a large part of the art rests on these human exchanges.

But the film nonetheless may have served as a turning point for the author. In his 2009 biography, “Gabriel García Márquez: A Life,” Gerald Martin writes that the experience of making “Tiempo de Morir” may have been what pushed the author deeper into literature, in which the writer has greater control over all aspects of the outcome — and where the cinematic can be conveyed in ways that transcend mere images.

“Film is extremely concrete,” García says. “Even now with the great resource of visual effects, you still need a great deal of mastery not just of technique but storytelling. To try to get poetry out of that will always be hard.”

Still, cinema would remain García Márquez’s passion, even if it was one he observed at a distance.

As he told the Paris Review in 1981: “My relation with it is like that of a couple who can’t live separated, but who can’t live together either.”

+++

When: 7:30 p.m. Friday

Where: Ford Theatres, 2580 Cahuenga Blvd. E., Hollywood

Tickets: $18 general admission; students and children 12 and under $13.

Info: fordtheatres.org and librosschmibros.org

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

ALSO

Director Rodrigo García’s life echoes across biblical ‘Last Days in the Desert’

Andrés Neuman crosses boundaries across the Americas in ‘How to Travel Without Seeing’

Why two artists surveyed the U.S.-Mexico border ... the one from 1821

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.