Awaiting the welcome return of performance to art museums’ mission

Shortly after assuming the helm as the fourth director of the Museum of Contemporary Art last month, Philippe Vergne visited the Los Angeles Times to meet with editors and writers. Still in the beginning stage of absorbing MOCA’s history and formulating his mission, he didn’t have a great deal to share about his plans.

But when asked whether he thought performance, a currently disregarded part of the museum’s founding mission, was important, Vergne answered that he wouldn’t call it important.

“It is essential,” he said reassuringly, after theatrically skipping a beat. Vergne has headed the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and Dia:Beacon in New York — places that put a premium on performance — and he explained that you simply cannot understand the contemporary art world without considering performance.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Nor can you appreciate the history of modern music without acknowledging its support from the art world. There have been a number of recent reminders, mostly overlooked, of the role that art museums in Los Angeles and elsewhere once played in fostering music’s more progressive inclinations.

One of those inclinations is Minimalism, the musical corollary to the art movement of the ‘60s. So with the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Minimalist Jukebox festival turning up the volume this week, it is worth dwelling on the synergy between the art and music worlds, which could use a boost at the moment.

The art world took an earlier interest in such pioneering Minimalist composers as Philip Glass and Steve Reich than did the vast majority of musical and academic institutions, which were downright dismissive of the movement. Both composers and their ensembles found the welcome in galleries and museums missing from concert halls or even on college campuses. Artists themselves came to the rescue as well. The sculptor Richard Serra once hired his like-minded SoHo neighbor, Glass, as a studio assistant.

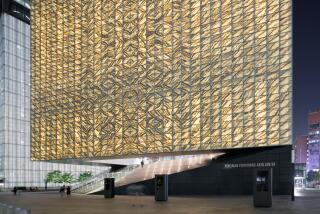

MOCA opened in 1983 two decades after Minimalism’s founding, and even then the museum was far ahead of the music establishment when it commissioned composer John Adams, choreographer Lucinda Childs and architect Frank Gehry to create a performance piece as the first public event of the Temporary Contemporary (now the Geffen Contemporary). Gehry had fashioned gallery space out of a former police garage downtown where MOCA could be based until its building on Grand Avenue was built.

At the time, Adams, curator of the L.A. Phil’s Minimalist Jukebox, was a 36-year-old second-generation Minimalist coming into his own. Childs had collaborated with Glass and director Robert Wilson on “Einstein on the Beach.”

The project was the brainchild of one of MOCA’s founding curators, Julie Lazar, who spearheaded the museum’s groundbreaking early media projects. She began by brokering an arranged artistic marriage.

None of the artists even knew one another. A photo of their first meeting in L.A. shows an enthusiastically baby-faced Adams seated at one end of a table. At the other end was Gehry, sporting long hair, oversized aviator glasses and a mustache, and staring straight into the camera with an I-can-do-anything confidence. Childs rested her head on her hand with an expression that read, “Oh, brother.”

PHOTOS: Best classical concerts of 2013 | Mark Swed

By launching itself with a performance, MOCA had signaled its multimedia and cross-disciplinary intentions from the start, and there was considerable skepticism from the music establishment, the art establishment and especially the critical establishment.

“Available Light” featured emotionally cool, high-speed choreography bathed in a drone-imbued electronic score. The audience sat in bleachers, surrounded by chain-link fence. If this was all the light available to MOCA, let there be darkness, was one memorable verdict in this newspaper.

We’ll soon have a chance to see just how much light “Available Light” might generate after 31 years. The Music Center has just announced that it will revive the work next year as part of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion’s 50th-anniversary season. My guess is that it will now seem visionary. Adams’ score, in which Sibelius-style brass chords penetrate Terry Riley-style synthesizer patterning, is a key transitional piece in his melding the repetitive obsessiveness of Minimalism with wider musical influences.

Moreover, the marriage took. Not only have the “Available Light” collaborators gone on to become leaders in their fields, they have continued to work together. Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall is an obvious inspiration for Minimalist Jukebox. Childs will direct a new production of Adams’ opera, “Doctor Atomic,” for Opéra National du Rhin in Strasbourg, France, next month.

PHOTOS: The most fascinating arts stories of 2013

There is no reason for any of this to take us by surprise. “Available Light” represents, if anything, a long tradition of museums fostering art as process not just objects. For instance, John Cage’s 1943 New York debut was hosted by the Museum of Modern Art. Time magazine took immediate notice. The New York Philharmonic, though, didn’t catch on to the composer — who would become in the next few years the leader of the New York School — for two more decades. Cage’s last public appearance, four days before he died in 1992, was also at MOMA, where his “Europera V” was receiving its New York premiere.

No notable New York opera company to this day, in fact, has staged a Cage opera. Nor has any major American opera company staged a Robert Ashley opera. Instead, “Crash,” the last opera of that crucial American opera innovator who died March 3, will be given its premiere Thursday in New York as part of the Whitney Museum Biennial.

Our local concert calendar this year alone has given us many reasons to recall the impetus art museums in Los Angeles and its environs once provided. An L.A. Phil Green Umbrella concert in January featured Pierre Boulez’s “Éclat.” Written in 1965, the score was finished in a mad rush at 1 a.m. the day of its premiere and the composer’s 40th birthday.

CHEAT SHEET: Spring arts preview 2014

It was rehearsed in the din of workmen also in a mad rush to finish a new theater. Who recalls that “Éclat” was commissioned for the opening of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and that the performance was, as was “Available Light” at MOCA, a new museum’s first public event?

As had been the case with “Available Light” helping liberate Adams, all that commotion surrounding the creation of “Éclat” led Boulez, around the same age and also in a transitional period in his work, toward a new, liberating direction. In “Éclat,” the cerebral French composer found an available new lightness, loosening his tight structural chains and allowing himself the freedom as a conductor to make split-second decisions on how the music might be played.

Boulez’s appearance was the first of hundreds of composers who brought new scores to LACMA over the years. Lawrence Morton, who ran the Monday Evening Concerts, had consulted with LACMA on the building of its Bing Theater, where his new music was installed when the museum opened. Stravinsky was a regular in the early years. Those early concerts at LACMA were also a proving ground for musicians such as conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, then a student at USC.

RELATED: More classical music coverage by The Times

The Monday Evening Concerts were unceremoniously dismissed during the transition from Andrea Rich to Michael Govan in 2006 (and it is now an independent series performing at the Colburn School). But for 40 years LACMA played a major part in modern music history.

LACMA now supports only a poorly funded, poorly promoted, if intelligently run, music series and demonstrates little institutional memory of its history in performance. If it did, you would think someone there would add a mention of music in the museum’s Wikipedia entry.Coincidentally, the Minimalist composer Meredith Monk will be performing at LACMA on April 11, but the museum did nothing to include that in the citywide Minimalist Jukebox.

Also in January, Jacaranda Music, the Santa Monica new music series, had a weekend celebration of the German installation artist and performer Mary Bauermeister. She had a studio in Cologne in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s where she hosted many of the most important European and American composers, Cage, Nam June Paik and Karlheinz Stockhausen included. The last time she had been in Southern California was in 1967, the year she married Stockhausen in California. The couple had come to perform at the Encounters series at the Pasadena Art Museum.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

That series, which included conversations with and concerts by some of the world’s most notable avant-garde composers ran from 1964 to ’73 (the last two years at Caltech). It happened to be the first place I encountered Cage, Stockhausen, Berio, La Monte Young (the first important performance in L.A. by the first Minimalist) and Messiaen. It made me want to live a life in music.

And it made others I knew at high school want to live lives in music. One went on to become a close associate of Leonard Bernstein and a collaborator on Bernstein’s Norton Lectures at Harvard. Bernstein’s late style might not have gone in the same direction it did had Tom Cothran not been a regular at the Encounters.

Only one museum has signed on to the Minimalist Jukebox, the Hammer. It helps launch the festival April 5 with a special performance of Terry Riley’s “In C” presented as installation art and will repeat it April 12. It is also the only venue to offer something in this festival to the public without charge. But one small museum can’t be expected to hammer in the morning, hammer in the evening for the cause of performance.

Nothing, then, could be more welcome than Vergne’s insistence that performance is an essential in the mission of a museum. Big spaces meant for displaying objects are also, in the modern world, places for making things happen. Let their available light shine in more ways than one.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.