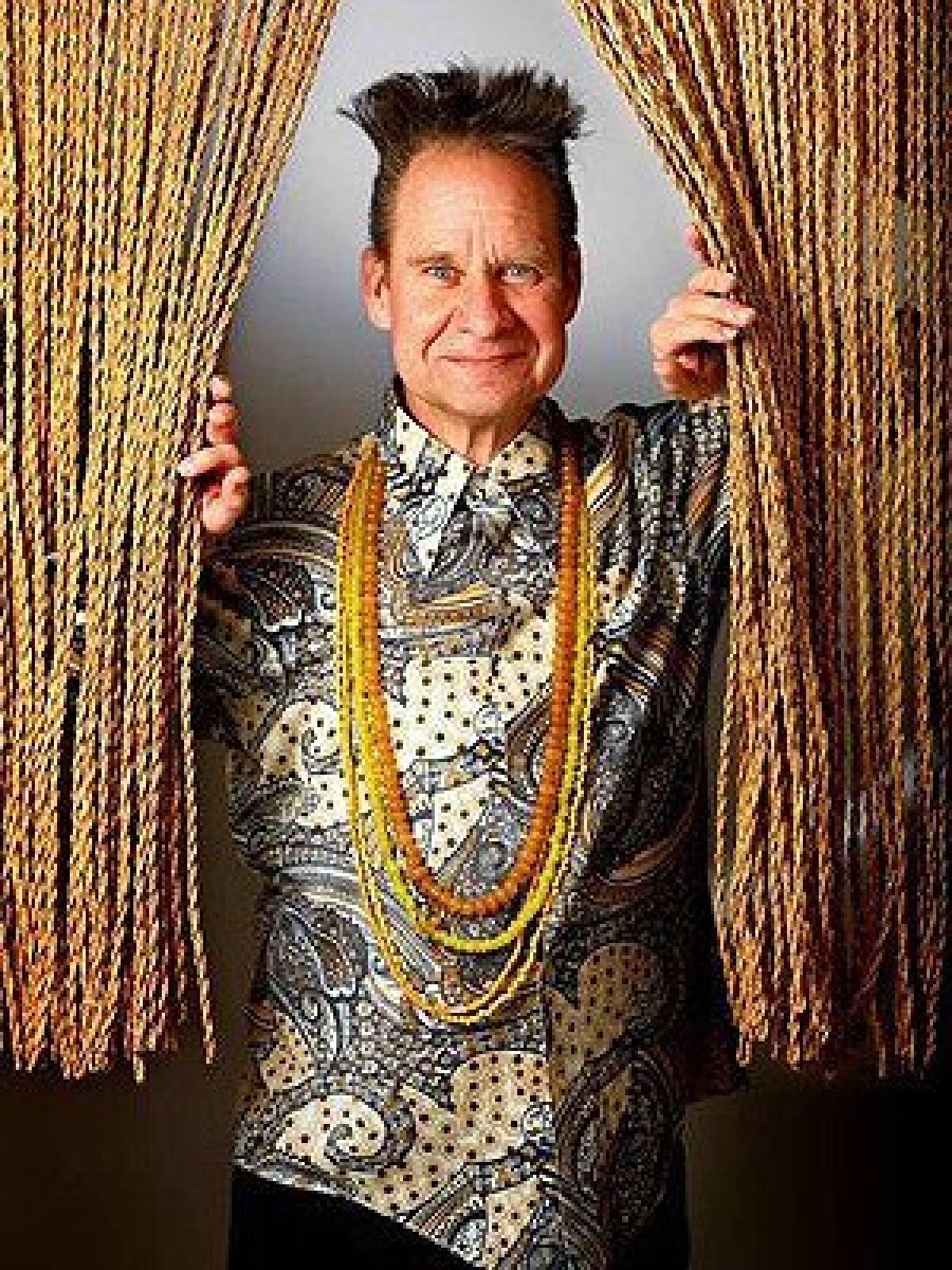

The Sunday Conversation: Peter Sellars

Theater director Peter Sellars, a UCLA professor of world arts and cultures, will be honored by the Santa Monica Museum of Art at its 25th-anniversary Precognito Gala on May 9.

Why are you based in Los Angeles instead of New York, which has a larger arts community?

For me, Los Angeles has always been the future and New York has always been the past. New York is the old power structure, and frankly, what’s way more interesting is what’s taking form in the 21st century in L.A. The future of America is happening right here.

You finally made it to the Metropolitan Opera in 2011 with “Nixon in China.” Was that important to you?

Not really. It’s nice, but I’ve been doing things all over the world for three decades. My world is in so many different places, and I’m just coming back from South Africa and Beirut, and I’m trying to go to Congo every two years. Again, the Met is another period in history, and I think that our generation and the next generation are really creating on a smaller scale — something that has way more intimacy, way more immediacy, that moves quicker and that is just lighter and has different color dynamics.

CHEAT SHEET: Spring Arts Preview

Is that partly a function of cost?

Totally, it’s a function of cost. It’s also a function of no hierarchy. The next generations do not need hierarchy, paying their dues and all that stuff. People are collaborating in totally amazing combinations just because of mutual interest, on the Internet and among people who know each other’s work.

Let’s talk about the Santa Monica Museum of Art. You brought Ethiopian artist Elias Simé to the museum’s attention, and the SMMOA mounted his first survey exhibition in the country in 2009. How did you discover him?

Actually, I was very, very fortunate, because what’s great in the arts is there’s a real network, so you hear about extraordinary people. In this case, I was asking Karen Higa, who’s a curator at the Japanese American Museum and a brilliant live-wire insightful presence in the art world here. I asked Karen, “Are there great African curators?” And she said, “There’s someone you need to meet, and that’s Meskerem Assegued.” I commissioned Meskerem to create an exhibit for the festival I created in Vienna, “New Crowned Hope,” in 2006. And I started meeting artists she thought I should meet and Elias was just an overwhelming person, and the body of work for 25 years is extraordinary.

When [Executive Director] Elsa [Longhauser] contacted me from the Santa Monica Museum and said, “If you created a show, what would it be?” And I said, “The work of this amazing Ethiopian artist.” And of course, L.A. has this wonderful Ethiopian community and all the cab drivers on the Westside, it created a really wonderful stir in parts of L.A. that you don’t always see at art museums. And that was very satisfying.

The directors of “Little Miss Sunshine” [Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris] were also friends of the Santa Monica Museum, and I said to them, “Go to Addis Ababa and make a movie.” And they actually did for their wedding anniversary. And they made a film of Elias in Addis, his daily life and making art — he has an incredible way to make art with these communities of kids — and that film was showing continuously at the museum.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

You visited the American University in Beirut. How did you find students there, compared to your students at UCLA?

That is one of the prestige universities of the Middle East, so you have students from very, very well-to-do and well-positioned families who really are going to step into leadership roles. And of course, what you feel at UCLA is a self-selecting group who are going to be the next elite. And that comes with all sorts of advantages and disadvantages, but you’re talking to people who are shaping the future, and that’s very powerful.

The other thing is the two campuses have a lot in common because the American University of Beirut is this mysteriously protected campus — it’s in one section of Beirut that has not been destroyed by bombs. And so it’s a strange slice of a dream of another Beirut, with its incredible greenery and these historic buildings, and it’s a little like UCLA’s surprising golf course campus in the middle of Los Angeles. It’s this bizarre green bubble that you can’t believe still exists.

You’ve said that “art over the past 25 years has failed to humanize the country.” How do you think it can accomplish that?

Let’s put it positively, because God knows there’s enough negativity in the world. The humanities were systematically removed from the menu of most Americans. So the result is you get a less humane civilization, and a society where torture is routine and we’re surrounded by every kind of petty and large-scale injustice. And we’ve all learned not to comment on it, not to make an issue of it, just to keep our heads down and keep moving. And that’s so not American and so not looking out for anyone else. And it’s deliberately neutering your own personal justice sensors.

And of course the humanities are all about activating your justice sensors and also about the empowerment of not just sitting there but actually realizing we’re all on Earth to be creative, to change things, to make powerful transformations in our lives and the world around us. And right now we are in such deep, deep, deep waters, and the only solutions are going to be the creative ones. And creativity is the very thing that has been removed from the school system. And that is shocking.

ART: Can you guess the high price?

You’ve been collaborating with Toni Morrison on “Desdemona,” which will be performed at the Holland Festival in Amsterdam in June and then at the Napoli Teatro Festival Italia 2013 in Naples. How did that come about?

I was having lunch with her one day and I mentioned there was a really bad play by Shakespeare called “Othello.” And then she spent four hours telling me how wrong I was. At the end of the lunch, we had a challenge — she challenged me to direct the play, which I did and I will continue to do. And then I challenged her to write a response to Shakespeare that really fills in all the missing links. The primary image of a black man in Western culture for 400 years is just not acceptable. And of course, Shakespeare couldn’t give you anything about where he grew up or the music he liked. And Shakespeare had just come off “Hamlet,” where the whole thing is soliloquies by the title character. “Othello” has one soliloquy that’s just 12 lines. Shakespeare just could not write for that guy.

So I asked Toni to please respond. And of course, Toni not only wrote an inner life for the guy, she took care of the women because she thought the women were underrepresented in Shakespeare. Without being pretentious, she can really look Shakespeare in the eye, and that’s incredibly exciting. We’re living at a time where we have such great writers and astounding musicians; that collaboration with Rokia Traoré, one of the great new voices of Africa and a stunning example of the new African women — super independent at home, all over the world, sophisticated in many cultures, but speaking powerfully for Africa.

You’re also working on a new production of Henry Purcell’s “The Indian Queen.”

I’ve just been downtown all week working with Gronk, that fantastic artist in the Chicano art movement, and Gronk is doing astounding work. “The Indian Queen” was written in 1695 by Henry Purcell, but he died while writing it. Purcell’s music is this jewel, the last statement of a great composer, but the libretto is a total mess, so I’m replacing it with a novel written in Nicaragua in the ‘80s by a wonderful writer, Rosario Aguilar, and she was looking around for accounts of the conquistadors by women. She didn’t find any, so she decided to write it herself. We’re going to stage the first contact without Cortez, without armies and without horses but the women who created a new culture and a new age. And the brilliant young choreographer Christopher Williams from New York and the incredible Chicano theater maker Robert Castro from San Diego. It will be a pretty exciting collaboration.

And to add to the exotica quotient, it will be performed in Perm, Russia. It is a genuine artistic hot spot in Russia at the moment. It’s the city that Diaghilev was born in but left.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.