Case study conservation on the Eames’ Case Study House

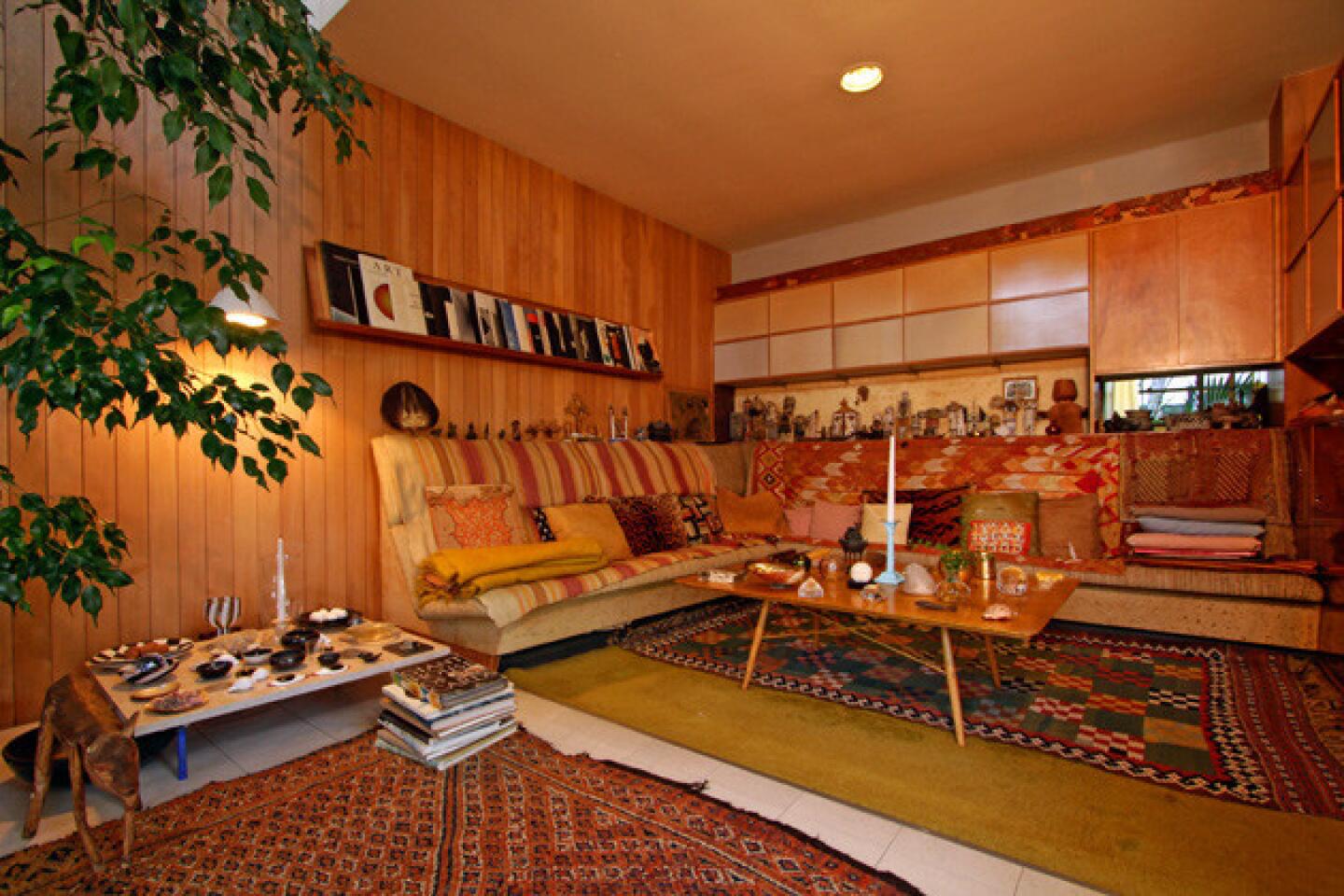

Surprisingly, little has changed at the Eames House since 1949, when Charles and Ray Eames designed their Pacific Palisades home and studio as a model of affordable modern living. Most of the objects they lived with remain in place at the two-part, rectangular structure on a bluff overlooking the ocean.

Charles died in 1978; his wife and professional partner passed away 10 years later. But they are remembered for their creative use of materials and innovative design of architecture, furniture and industrial products.

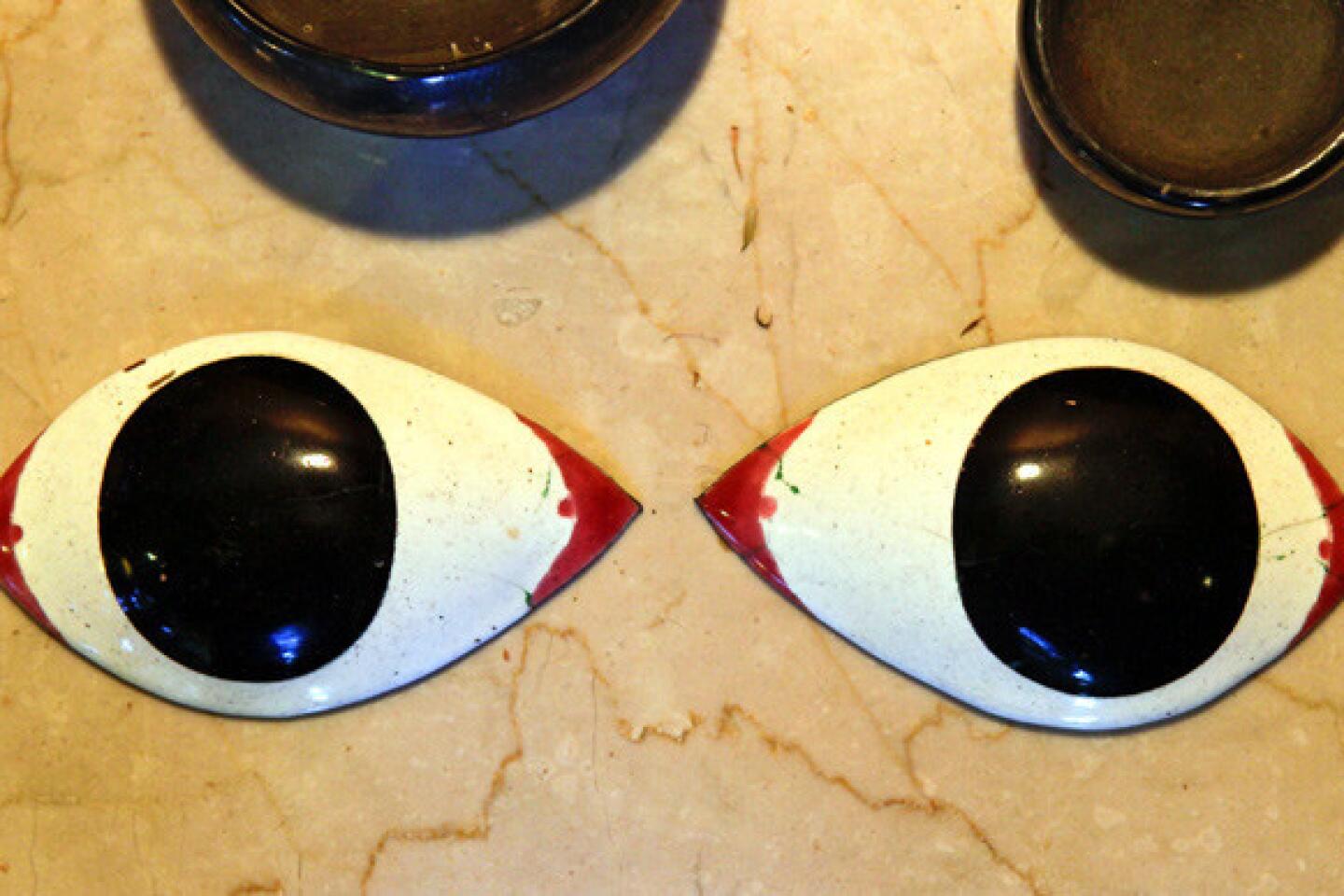

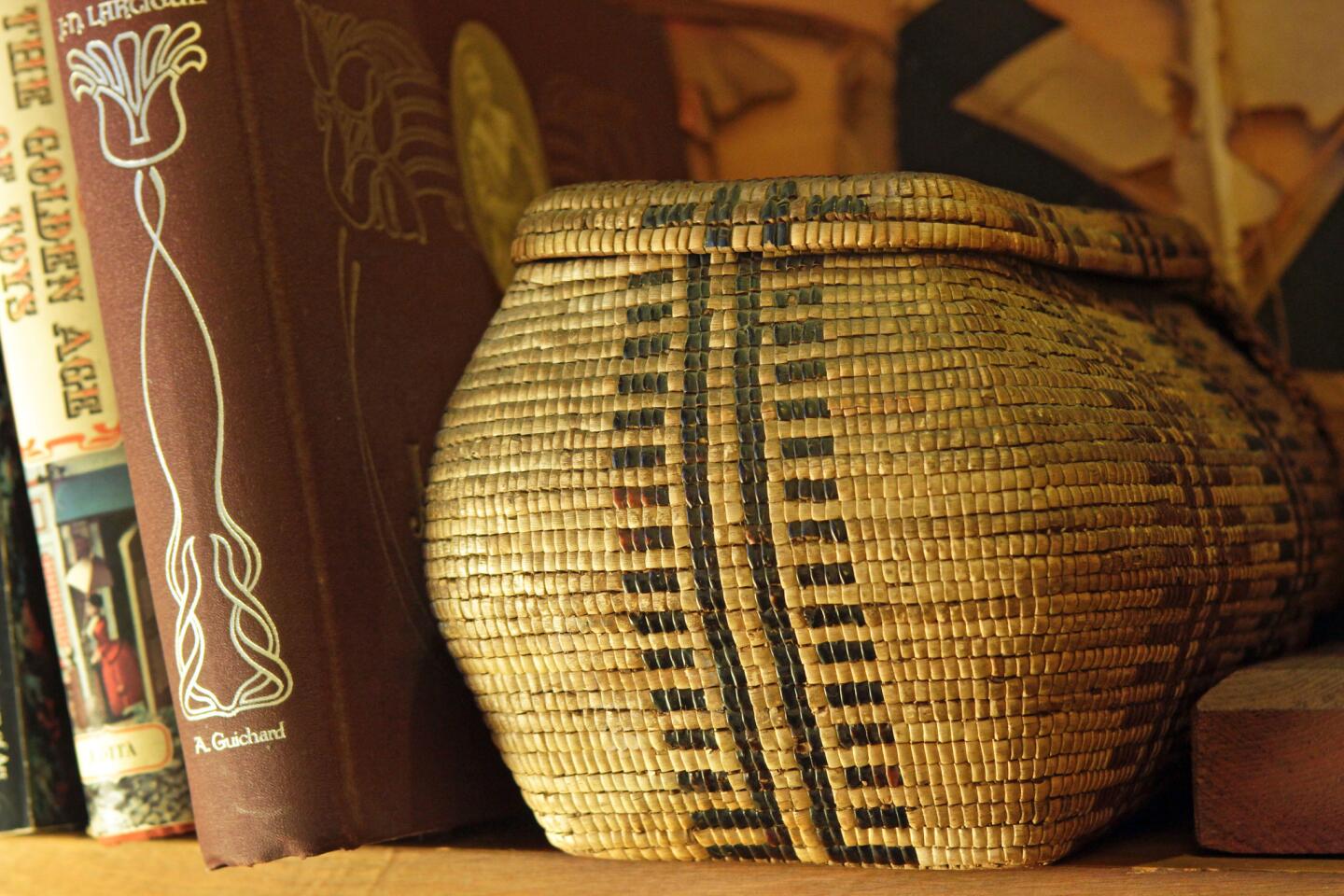

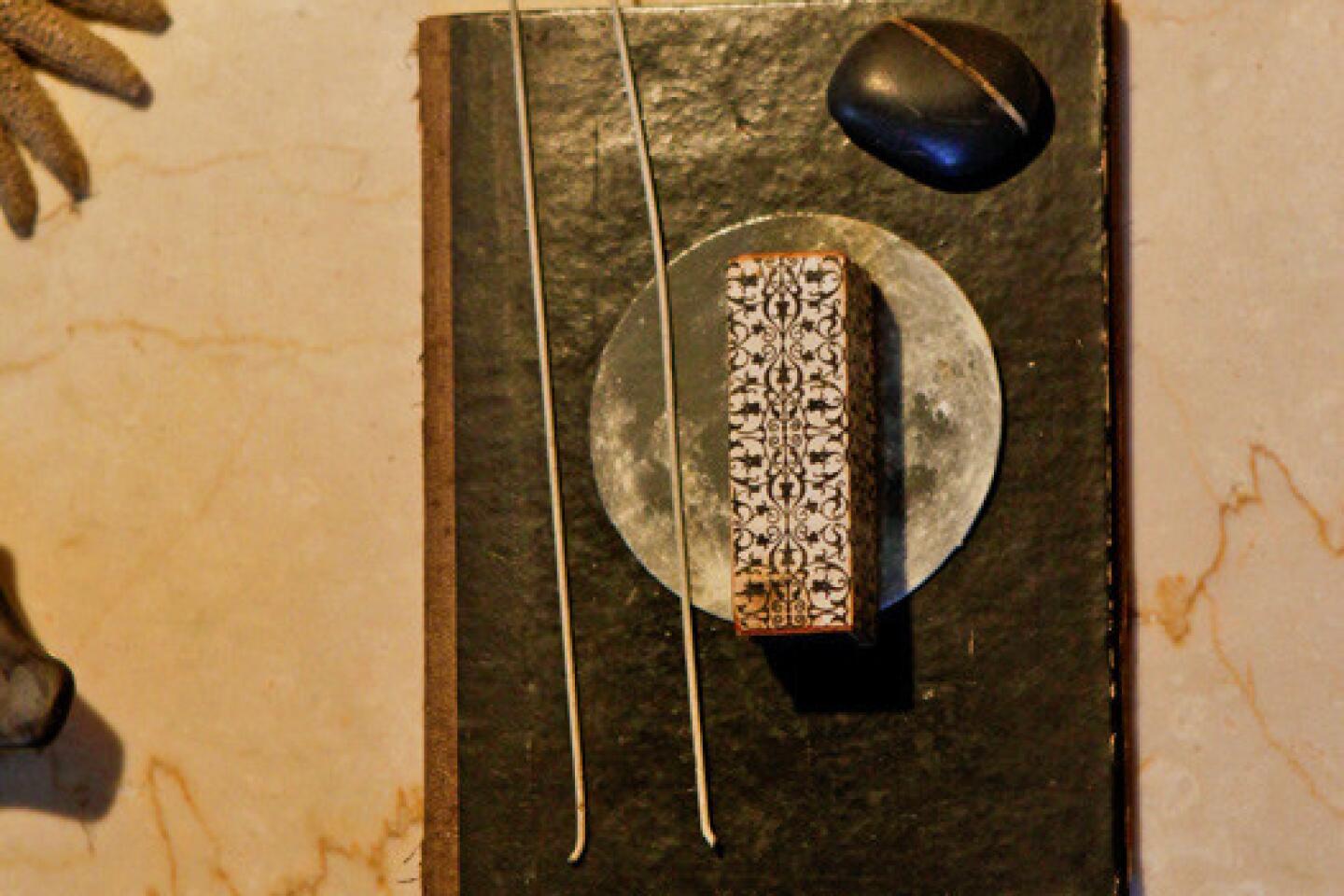

Ray’s colorfully patterned dishes, place mats and napkins are stacked in kitchen cabinets. The couple’s clothes fill upstairs closets — suits and dresses on hangers; shoes on the floor; sweaters, hats and scarves in boxes. Their playful approach to design and love of nature linger throughout the space in whimsical folk art, clusters of seed pods and little piles of smooth stones.

FULL COVERAGE: 2013 Spring arts preview

But wait. What’s that windmill-like contraption perched on the ocean side of the grounds? Why do electrical wires and monitoring devices pop up here and there in the house? And why has a tiny section of black paint on a window frame been scraped away, revealing underlying colors?

All these curiosities, along with a new white tile floor in the living room, are evidence of a collaborative effort to conserve a landmark of mid-20th century modern architecture. The Eames House is the pilot project of the Conserving Modern Architecture Initiative, launched last year by the Getty Conservation Institute.

Conceived as an experiment in postwar California living, the house emerged from the Case Study Program initiated by John Entenza, editor of Arts & Architecture magazine. With the idea of using new materials and techniques to provide well-designed, mass-producible housing for average Americans, forward-thinking architects such as Charles Eames, Pierre Koenig, Eero Saarinen and Richard Neutra were invited to participate in the program and contribute their own ideas.

Today, the unconventional Eames residence — constructed of prefabricated materials and off-the-shelf products but highly customized — is in the forefront of a struggle to prolong the lives of notable modern buildings.

“Our projects aim to advance conservation practice in some way,” says Susan MacDonald, head of the GCI’s field projects. “The Eames House is of international significance and demonstrates a number of challenges that are shared across houses from this period that are publicly accessible — from environmental issues and collections management to physical conservation challenges related to the use of modern materials.”

Future projects have to be determined, says MacDonald, who is pleased that the first one is in Los Angeles.

“There couldn’t be a better case study for our initiative,” says Kyle Normandin, an architect with extensive conservation experience who is managing the program for the GCI. He came to the Getty from Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates Inc. in New York City.

Starting with a needy building of such a high caliber, he says, will emphasize the urgency of the mission.

The timing couldn’t have been better either. The Eames Foundation — charged with preserving the house and the designers’ creative legacy — asked the Getty for help just as the initiative was taking shape. In another stroke of luck, a request from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to re-create the Eames’ living room for its 2011-12 exhibition “Living in a Modern Way: California Design, 1930-1965” coincided with the necessity of replacing the original floor.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

The tiles were brittle and laden with asbestos, and the adhesive attaching them to the concrete slab had been destroyed by moisture seepage. It wasn’t easy to figure out a waterproofing system for the concrete, find a tile adhesive that would emit no dangerous gases and ferret out asbestos-free tiles that looked like the originals.

But instead of being confined to storage for the duration of the work, the furniture and other contents of the room were a highlight of LACMA’s popular and critically acclaimed show. “Living in a Modern Way” is at the National Art Center in Tokyo until June 3, but the Eames living room material didn’t travel with it. The show was part of the Getty’s original “Pacific Standard Time” exhibitions.

The foundation approached the Getty for general guidance as well as advice on specific issues, says Lucia Dewey Atwood, a member of the foundation’s board and a granddaughter of Charles and Ray Eames. The floor was done first because of the exhibition.

“Our situation is very unusual,” Atwood says, “because we are not just preserving the structure. We are preserving the contents, and at times, those two things come into conflict.” One obvious difficulty is that light streaming through windows of a house designed as an indoor-outdoor space inevitably damages sensitive fabrics and artworks.

Members of the Getty team, including GCI scientists and conservators at the museum, will offer advice to the foundation, based on a variety of tests and analyses. They will also help to develop a long-term conservation management plan.

“In this particular case,” Normandin says, “it isn’t just the environment of the house. It’s the environment of the site. The house sits in a meadow overlooking the ocean. There’s a marine environment. We need to look at temperature fluctuations on a day-by-day basis, humidity levels and how they change over time, as well as wind, precipitation and temperature differentials.”

What looks like a spindly windmill is a weather station that downloads information and transmits it to the GCI. Inside the house, a different monitoring system measures temperature, humidity and light.

“We wanted to compare data collected over a long period of time at the weather station with what was happening in the interior of the house,” Normandin says. “A holistic program of monitoring is going to give us an opportunity to fine-tune a climate control system that the Eames Foundation will be able to use in the future, one that will stabilize the environment of the house and protect the contents and interior finishes.”

(The property continues to be open for tours by reservation, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. daily except Sundays and Wednesdays. Visitors cannot go inside the house, but much of the interior can be seen from outside.)

Other investigations of the structure have already produced results. GCI conservator Emily MacDonald-Korth’s excavation of paint on a steel window frame showed that the familiar black top coat covers hand-mixed grays, probably created by Ray Eames. Atwood says the tests show that the grays were tinted with mineral pigments, including red iron oxide, Prussian blue and chrome yellow, and they confirm verbal and written accounts of paint colors in earlier days.

Yet another exploration has solved a mystery — the identity of wood on a living room wall that continues outside under a roof. Getty Museum conservator Arlen Heginbotham got the job and determined that it is a species of eucalyptus, commonly known as Australian tallowwood and quite similar to the large eucalyptus trees alongside the house.

“We don’t think for one second that choice was accidental,” Normandin says. “Charles and Ray obviously picked a very warm wood that could be used in the house and tied in with the landscape that they enjoyed so much.” It has now been lightly cleaned and varnished to maintain its original appearance.

“What’s so exciting to us,” Atwood says, “is that this project echoes the original Case Study Program.”

Just as the postwar program was meant to make cutting-edge housing widely accessible, the Eames House project is intended to have a far-reaching impact.

“We must share our findings, with the hope that other people can adapt it knowledgeably to their own needs,” Atwood says.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.