‘The Flying Dutchman’ in L.A. a high for international opera stars

Amid the just-quieting lunch rush at Kendall’s Brasserie in downtown Los Angeles, there is no question who the international opera stars are. Portuguese soprano Elisabete Matos and Icelandic baritone Tomas Tomasson sit tucked away at a nondescript table; but their clear, mellifluous voices cut through the din of the restaurant. When Tomasson chuckles, it sends a gentle, merry rumble across the floorboards.

Both performers are new to L.A., a city Tomasson finds “huuuge!” he bellows.

Another first: the singers will see their L.A. debut in “The Flying Dutchman,” which opens at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on Saturday. The lavish Wagner opera is part ghost story, part love story, the tale of a cursed sea captain who must wander the stormy ocean with his crew for eternity until he finds true love, which breaks the spell. Tomasson anchors the production as the Dutchman and Matos plays his salvation, Senta — both roles they have performed multiple times before, just not together.

PHOTOS: LA Opera through the years

“He personifies the loneliness and suffering of the human condition,” Tomasson says of his character. “It’s very dramatic.”

Daniel Dooner will direct the Nikolaus Lehnhoff production, which premiered at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 2001 and played at the San Francisco Opera in 2004. It’s a straightforward interpretation, presented without intermissions over two hours and 20 minutes, the way Wagner had intended.

Matos — who last performed the role of Senta in 2010 at Madrid’s Teatro Real — says that in this particular version of “Flying Dutchman” her character is “more active, more driving of the action. She has this craziness, she makes everything happen.”

Tomasson — who transitioned from bass to baritone seven years ago and who last starred as the Dutchman in 2007 at Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu — never intended to be an opera singer. In college in his hometown of Reykjavik he set out to become an astrophysicist. He joined the college choir simply because it was the largest social network he could find, he says. The first opera he saw was “Aida” when he was 20.

“It was such an overwhelming experience,” says Tomasson, 47, who now lives in Berlin. “I fell in love with it and wanted to be an opera singer.”

For Matos, 49, music was an integral part of her upbringing. Her father played trumpet and she started playing the violin at age 9, something she aspired to do professionally; she began voice lessons as a teenager. The drama of opera and the liberation of playing a character led her to pursue it as a career instead of the violin, she says.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

“It’s a way to not be Elisabete Matos, but to be a different person — a very bad woman, a very nice woman, to have all the possibilities of living this character,” she says. “On stage, you have the courage to show your emotions.”

Matos met Spanish tenor and L.A. Opera general director Plácido Domingo in 1997 when they were both performing in the world premiere of Antón Garcia Abril’s “Divinas Palabras” in Madrid, where she now lives. He invited her to try out for Jules Massenet’s “Le Cid,” which he would soon be starring in at the Teatro de la Maestranza in Sevilla and the Washington Opera (now the Washington National Opera) in 1999. She landed the role of Chimene in both productions — Washington was her U.S. debut.

“I had paid my dues. But it was the moment of singing with Plácido that took my career to the next level,” she says.

This May marks the 200th anniversary of Wagner’s birth — something that is being celebrated by opera enthusiasts worldwide. As a result, says Domingo via email, the L.A. production of “Flying Dutchman” was particularly tricky to cast.

“Every opera company has been competing for all of the same singers during the Wagner bicentenary,” Domingo says. “Fortunately, the timing worked out to bring these two leads to Los Angeles for their debuts here. Elisabete is a wonderful artist ... the Dutchman has become a signature role for Tomas.”

Rehearsing for the first time in Southern California has had its challenges for both singers. The dry climate and central heating has wreaked havoc on their vocal cords, for one, so they have to drink inordinate amounts of water to keep their voices fit for performing, Tomasson says.

PHOTOS: LA Opera through the years

“It affects your breathing. And we don’t use microphones, there’s no amplification,” he says. “With these tiny little vocal cords, we have to fill 4,000-seat theaters.”

Then there’s the rigorous schedule of traveling, says Matos, who finished a concert in Lisbon before immediately heading to Madrid to pack and then jetting off to L.A. the next morning for the first of four weeks of rehearsals.

“In the old days, opera singers traveled by ship,” she says. “Nowadays, we live in a more immediate world. It’s good to have work, but your vocal cords, your brain and everything else needs rest. You sing with your whole body.”

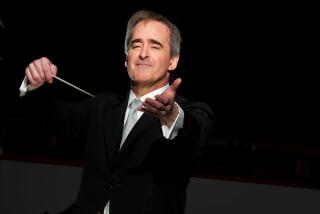

Still, they agree that the L.A. production of “The Flying Dutchman” is a dream realized for both singers, who have long wanted to perform with the L.A. Opera. They are especially pleased that the company’s music director, James Conlon, will be conducting.

“The quality of an opera company is always grounded in the quality of the orchestra,” Tomasson says. “And L.A. has been high on my list.”

At a recent Music Center rehearsal, amid the tangle of technicians, soloists and musicians milling about onstage — all of whom appear dwarfed by an ominous, towering shadow of the Flying Dutchman looming on a scrim over the stage — there actually is some question as to whom the international opera stars are from the near-vacant seats in the audience.

That’s exactly the point, says Tomasson, who sees opera as more collaborative than any of the other performing arts.

“We’re a big, organic mass,” he says. “Like instruments working together. From the 100-piece orchestra, 60 to 80 chorus members, soloists and enormous amount of technicians — it’s such a huge group effort. That’s part of the magic and beauty of this art form.”

MORE

INTERACTIVE: Christopher Hawthorne’s On the Boulevards

Depictions of violence in theater and more

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.