Music review: International Contemporary Ensemble’s movie mood

In the decade since its founding, the International Contemporary Ensemble has become essential. The flexible collective of 33 musicians is likely the most accomplished new music group in New York, and it makes a significant contribution toward keeping the city musically cosmopolitan, regularly providing compelling performances of meaningful and dauntingly difficult new music from afar.

One of the most memorable concerts of recent work I’ve heard in the last half-year, for instance, was ICE’s program devoted to the feisty, remarkable Austrian composer Olga Neuwirth at Columbia University in December. Hardly unrecognized, ICE (which also has a Chicago presence) will once more be artists in residence at Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival this summer, and ICE’s flutist, artistic director and chief executive, Claire Chase, received a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant last year.

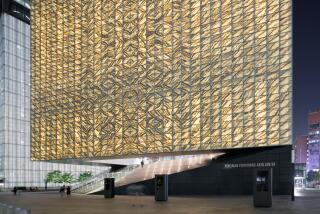

So it is hard to believe that only Saturday night did ICE finally make its Los Angeles debut. Equally hard to believe was that the debut came at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Less hard to believe was that the L.A. new music community once more boycotted the museum. Such is the bitter resentment for the museum’s having dumped the acclaimed Monday Evening Concerts series seven years ago (even though MEC is just fine, thank you, as an independent outfit performing at Zipper Concert Hall).

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

The current regime at LACMA wasn’t all that kind at first to film, either, but the attempt to drop its screenings was met with enough resistance from the public, the press and Martin Scorsese in 2009 that the administration backed down. At the moment, the museum has two major film director exhibitions, one that grandly fetishizes Stanley Kubrick and another that offers valuable context to the exceptional career of Hans Richter. By (no doubt) coincidence, these happen to have been two musically searching filmmakers, and that is what Saturday’s program explored. It proved an apt occasion for LACMA to start to make amends for its past slights to sound as well as pictures that move.

A small start is better than none, of course. The first half of the program was a modest tribute to music related to Kubrick and Richter, played along with film clips. After intermission, ICE presented one of its glories, a performance of Peter Maxwell Davies’ 1969 avant-garde classic, “Eight Songs for a Mad King.”

There were compromises. LACMA brought only six members of ICE (flute, clarinet, violin, cello, percussion and piano). Worse, the Richter clips of films from 1929 to 1947 were projected stretched and cropped. In “Dreams That Money Can Buy,” Richter invited Marcel Duchamp to create optical illusions with twirling discs and John Cage to accompany that with a prepared piano piece. ICE pianist Phyllis Chen played Cage’s “Music for Marcel Duchamp” live; overhead Duchamp’s circles became ovals and his descending nudes, pleasingly plump.

There were two premieres. Chicago-based Brazilian composer Marcos Balter composed a short piece, “Ligare,” based on György Ligeti’s “Lontano,” which Kubrick used in “The Shining.” Balter’s seven-minute score is a quiet, understated study in color; timbres change when pitches don’t.

Kubrick used more Ligeti in “Eyes Wide Shut,” and Chen played the second movement of his “Musica Ricerata” that accompanies a street scene with Tom Cruise. The pianist also supplied a delightful new score to accompany a Richter silent short, “Everything Turns Everything Revolves,” for violin clarinet, toy piano and other noisy playthings. There was something called a crackle box that crackled. The movie is Dadaist, with crazy things and people popping up, and Chen’s madcap music was just right.

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

Davies’ “Mad King,” however, went astray. In the past, ICE had experimented with tenor Peter Tantsits and the director Lydia Steier, who used live video in the performances. But Tantsits was not available, so ICE percussionist Ross Karre recorded a video of him, and for the first time the group played along with that.

In Davies’ work, we get glimpses of King George III reacting to birds, fantasizing about an old mistress, recalling the country, the Thames, the land of sheep and cabbages, as he becomes unhinged. In the new film, Tantsits spends the work’s 38 minutes in front of the mirror, powdering his face, putting on his wig, sticking a pencil deep into his cheeks to make a mole.

Madness can have many faces; this one, though, felt limited. The sound system wasn’t special, just loud. The tenor gets more than a little carried away at times, and that hurt the ears. That left the instrumentalists as mere accompaniment, which was the greater pity, not only because the players were terrific but also because this is where you really do want distortion. It is through their 20th century lens that the 18th century becomes surreal.

Still, LACMA has at least given us a taste of ICE. Now let the ensemble return — soon and in its full glory.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.